6.7-6.8 ...but of course you’re not a nihilist! Give me an honest answer, an honest one, do!

The last two chapters of the novel's main plot. It has been a long journey—11 days for Raskolnikov, six months for us. Only the epilogue remains.

Hello, Dostoevsky enthusiast!

For those who have just joined us in connection with reading The Brothers Karamazov next year, I welcome you and let you know that this and the next article will be about Crime and Punishment. We are finishing reading it, so if you don't want any spoilers, you should stop here and wait until January for full immersion. But if you want to join the discussion of the final chapters of the novel, you are most welcome.

Organizational post about The Brothers Karamazov you can find here

List of articles by chapters you can find here

Reading schedule is here.

Today, we will discuss and explore the meanings of the final two chapters of the main part of the novel. Raskolnikov finally makes his choice—reluctantly and hesitantly. Even at the last moment, he runs out of the police station, but upon seeing Sonya, he returns and puts an end to his indecision. Let's take a poll - what did you think Raskolnikov was more likely to do?

It takes 11 days from committing the crime to confessing to it

He kills the old woman and Lizaveta on July 9th and confesses on the evening of July 20th. Having spent several days unconscious with fever, he effectively has only a week to process everything. This is remarkably brief for someone to transition from murder to confession, especially since the idea of murder had been growing in him for months, perhaps even a year. When an idea is so deeply rooted, it’s impossible to completely abandon it in just a week—which is precisely why Dostoevsky depicts Raskolnikov’s torments and doubts about surrendering to the police.

His nighttime wanderings in the rain along the Neva, contemplating suicide, terrify him more than the prospect of prison. Significantly, he wandered in the rain on the eve of St. Elijah’s Day—a time when folk belief attributes a cleansing power to the rain, capable of washing away all "impurity." Thus, both characters—Raskolnikov and Svidrigailov—are symbolically cleansed of their "impure" forces and come to understand how they should proceed. However, their outcomes diverge: one is pagan (Svidrigailov), and the other is Christian (Raskolnikov).

More about the significance of July 20th and St. Elijah's Day can be read in the article about the previous chapter.

Despite Raskolnikov's efforts to become a detached killer—someone capable of murder without emotional consequence—the act leaves him profoundly traumatized. Yet this very trauma becomes his salvation, as it allows him to open his heart to Sonya and preserves his ability to love, especially his mother and sister.

The Last Meeting with Mother

Before leaving, Raskolnikov goes to say goodbye to his mother and sister. His mother reads and rereads the article brought by Razumikhin, in which Raskolnikov outlined his theory. For the first time, Raskolnikov sees it in print, and although he experiences a brief "caustic-sweet" feeling—typical of an author first holding their published work (as the narrator pointedly notes)—he quickly throws the article aside "with disgust and annoyance." Yet now, Pulkheria Alexandrovna is retelling his ideas. Wasn’t it she and his father, a failed writer, who had once instilled such notions in their beloved Rodya?

"You will very soon be one of the first, if not the very first in our scholarly world [...] Ah, these base worms, how can they understand what intelligence is!"

Raskolnikov asks his mother for forgiveness but doesn’t confess his crime to her. He assures her that he loves her "more than himself" and asks her to pray to God for him. Notably, he had earlier made the same request to Polechka, Katerina Ivanovna Marmeladova’s eldest daughter.

A few words should be said about Pulkheria Alexandrovna’s behavior: her strong bias toward her children is apparent. Rodion, despite behaving like an absolute wretch toward her, remains her beloved. She avoids troubling him or asking probing questions, while her tone about Dunya, who has simply gone out on errands, is notably different. This overprotectiveness likely influenced Rodion’s development, possibly enabling his belief that he could be a "superman.”

It’s also worth noting that this is the last time Raskolnikov sees and speaks to his mother. This poignant farewell is why many film adaptations of the novel depict this scene as deeply emotional, highlighting the final embrace between mother and son.

The Capitol

After receiving his mother’s blessing, Raskolnikov returns to his room, where he meets Dunya, who already knows everything.

"I’m going now to turn myself in. But I don’t know why I’m going to turn myself in," he tells his sister. The breakthrough hasn’t happened yet. He still expresses his earlier convictions with the same fervor as when his theory first took shape.

"Crime? What crime?" he suddenly cried out in fury. "That I killed a vile, malicious louse, an old pawnbroker woman, needed by no one, whose death would be forgiven forty times over."

Raskolnikov still sees himself as a hero—like those in folk legends whose sins are forgiven when they vanquish villains who prey on the poor. Why, then, does everyone keep pointing at him, crying "crime, crime"? To Dunya’s desperate exclamation that he has shed another’s blood, Raskolnikov responds:

"Blood which everyone sheds, which flows and has always flowed in this world like a waterfall, which they pour like champagne, and for which they crown them in the Capitol."

This response reveals the presence of pagan motifs in Raskolnikov’s worldview.

The Capitol—broadly one of the seven hills of ancient Rome, and specifically one of the two peaks of Capitoline Hill—was home to the temple of Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva, serving as the Empire’s political and religious center. It was the endpoint of triumphal processions that began at the Field of Mars. The triumphator, embodying Jupiter, would stand on a decorated chariot pulled by white horses, dressed in purple robes embroidered with gold, and holding an ivory scepter and a laurel wreath (corona triumphalis). Behind him marched his soldiers and noble captives. The procession culminated with the triumphator presenting his laurel wreath to the temple of the three gods. (Although Raskolnikov’s reference isn’t entirely accurate.)

A triumphal procession was organized only by decree of the Senate and only if at least 5000 enemies were killed in the battle won by the commander. Lesser victories merited a minor triumph (ovation), where the commander ascended Capitoline Hill on foot, wearing a myrtle wreath instead. A notable example occurred in 46 BCE, when the Capitol hosted a grand triumph for Gaius Julius Caesar after his victory over Pompey Gnaeus at Thapsus—a victory that, along with his subsequent triumph at Munda the following year, solidified his position as Rome’s absolute ruler.

As we can see, Raskolnikov’s confessions—even those made during crucial moments to Sonya—ring hollow. He remains entrenched in his theory and his own sense of righteousness.

Never, never have I understood this more clearly than now, and more than ever I don't understand my crime! Never, never have I been stronger and more convinced than now!

Portrait of the Fiancée

Dostoevsky provides further insight into Raskolnikov's deceased fiancée, Natalia Egorovna Zarnitsyna. Though their relationship remains vague throughout the story—his interactions with her mother, the apartment’s landlady, hardly suggest Natalia’s significance—the topic resurfaces, particularly when Pulkheria (Raskolnikov’s mother) disparages the deceased girl.

The loss of his fiancée clearly devastated Raskolnikov. She had been his confidante, the one person with whom he could discuss anything openly. His careful preservation of her portrait and tender references to her memory speak volumes. Natalia seems to have been both intelligent and understanding, accepting his ideas without judgment. Like Sonya, she was deeply religious, with a similar gentle temperament, and had even considered entering a monastery.

Her death likely triggered Raskolnikov’s descent into depression, causing him to withdraw and isolate himself in the same room they had shared. Pulkheria’s callous remarks about being relieved by Natalia’s death and her opposition to their marriage likely deepened his trauma. She would voice these opinions openly, often cloaking them in false disclaimers like “I shouldn’t say this” or “I didn’t want to say this”—only to say them anyway. Such behavior causes lasting wounds and drives people apart.

The Cross and the Crossroads

Pride and hatred for humanity continue to torment Raskolnikov on his way to the police station. This hatred, which has replaced love, resides in his heart—the same demon Razumikhin once saw in his eyes, the one that "hardens" his soul after the murder.

Before turning himself in, Raskolnikov visits Sonya, who places her cross around his neck, as they had agreed. We know that Lizaveta, Raskolnikov's second victim, and Sonya were friends who had exchanged crosses, marking them as sisters in faith. Now, Sonya gives her cross to Raskolnikov—not as part of an exchange, but as a powerful ritual: placing her cross on the man who killed her spiritual sister. This cross represents the strength of love, faith in humanity, and mercy. It is made of cypress—an evergreen tree native to the Mediterranean. According to folk beliefs and spiritual verses, Christ was crucified on a cross made of cypress.

Yet despite this profound sacrifice, Raskolnikov irritably tells Sonya that she’ll merely be his nursemaid. When she tries to accompany him to the police station, he dismisses her harshly. Tormented and cursing both himself and others, he finally proceeds to the station.

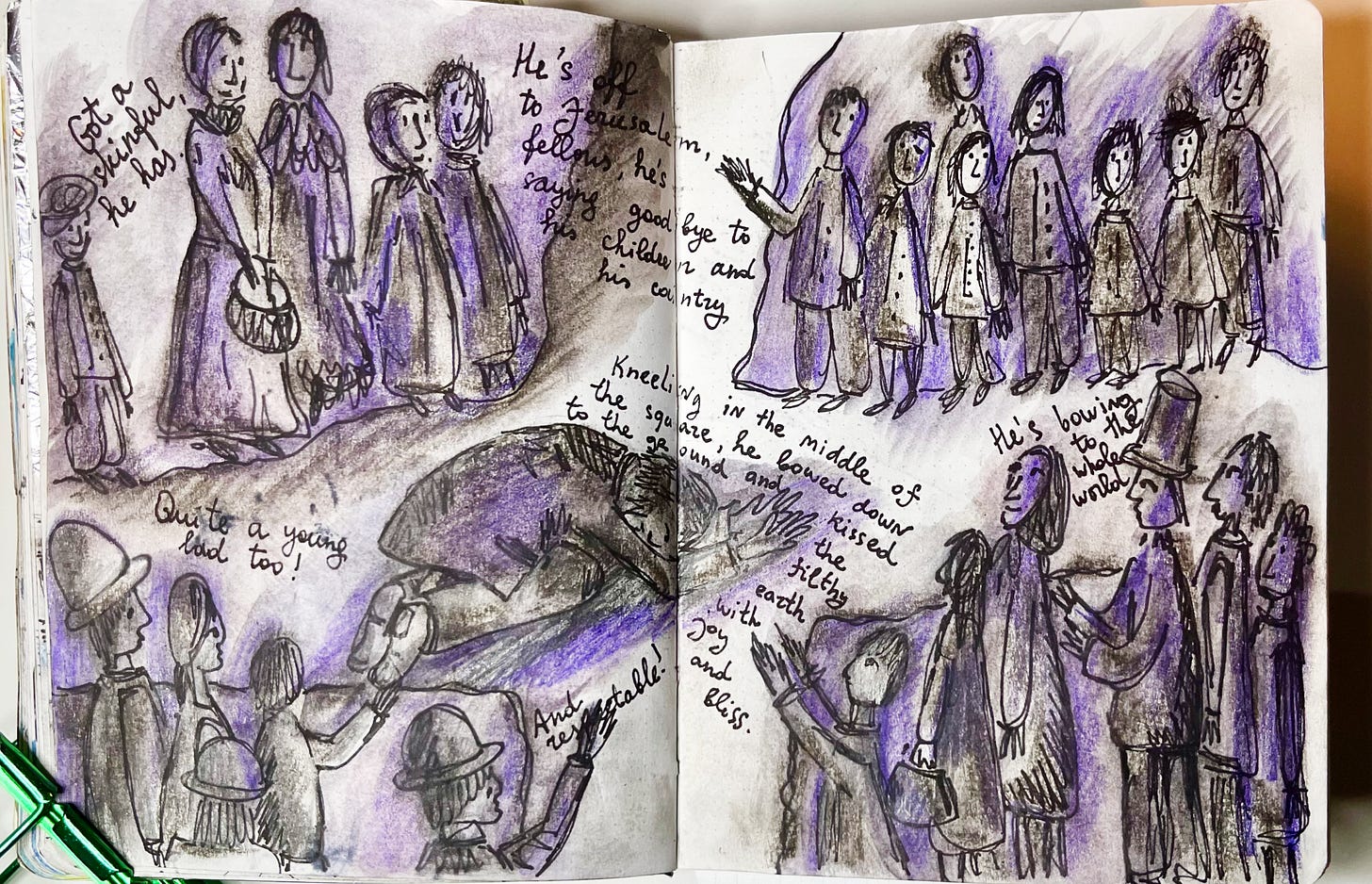

In Haymarket Square—a gritty marketplace teeming with merchants and crowds—a strange sensation suddenly "seizes him entirely—body and mind." Raskolnikov steps into the square, bows to the people, and kisses the ground "with pleasure and happiness." Yet, true redemption and reconciliation with the world remain distant.

"He suddenly remembered Sonya's words: 'Go to the crossroads, bow to the people, kiss the earth, because you have sinned against it too...'"

A crossroads serves as both the devil’s ground and God’s domain. While many approach crossroads for diabolic pacts, Rodion comes to stand before God and the people, seeking forgiveness—once again evoking the motif of Cain and the burden of blood.

The theme of guilt before the earth intertwines with that of earthly repentance, subtly woven throughout the novel. In Slavic folk spiritual verses, these themes often merge with the belief that murder defiles the earth. Below is an example of such a poem in free translation, followed by the original text1.

The good young man repented to the raw earth.

To the raw earth and the raw mother:

Forgive me, forgive me, dear Mother Earth.

Forgive me, forgive me, raw mother.

And forgive me too, as a good young man.

I roamed, the good young man, across the open field,

And I killed, in the open field, a merchant, a trading guest...

The folk-religious practice of repentance to the earth is not only reflected in folklore but was also alive among people in rural areas. There is evidence that in the mid-19th century, "Old Believer interpretations" spread and confessed their sins not by going to confession in church, but by falling to the earth. In general, this is what the schismatics did, after whom Rodion is named — Raskolnikov (Raskolnik, раскольник).

If you missed this detail about the surname, you can read about the Raskolniks in the article about Mikolka and Zaraysk (6.1-6.2)

Finally…

Nevertheless, Raskolnikov proceeds to the police station, intending to confess specifically to Lieutenant Ilya Petrovich Powder—the officer who had offended him during their first encounter the day after the murder. However, this time, Powder greets Raskolnikov enthusiastically, admiring his erudition and even apologizing for his earlier behavior.

"Your career lies in academia, and setbacks won't deter you anymore. For you, all these beauties of life are, one might say, nihil est2, you're an ascetic, a monk, a hermit."

Like all self-absorbed individuals, Raskolnikov is susceptible to flattery. As a result, he loses his resolve and leaves the police station without confessing. Before departing, however, he learns of Svidrigailov’s suicide—and realizes that he might share the same fate.

In the novel's draft notes for the finale, there are these remarks:

"Raskolnikov goes to shoot himself. Svidrigailov: 'I'd be glad to go to America right now, but somehow nobody wants to.' Svidrigailov tells Raskolnikov in Haymarket Square: 'Shoot yourself, and perhaps I'll shoot myself too."

Outside the police station, Raskolnikov encounters Sonya, who immediately understands his failure. She looks at him with wild desperation, throwing up her hands. Her reaction prompts Raskolnikov to return to Powder with a smirk and confess his crime.

What ultimately drove Raskolnikov to confess? In my opinion, two main reasons stand out:

He fears that without prison, he’ll meet Svidrigailov’s fate, likely at the bottom of the Neva River.

Sonya’s unwavering strength and faith in him deeply moved him. Witnessing her courage, he chose to follow his conscience. He realized the value of his soul and couldn’t bear to disappoint her.

Did he repent? No. At this point in the story, Raskolnikov feels no genuine remorse. The journey of his soul is not yet complete—we still have the epilogue to read and discuss.

An interesting point:

Dostoevsky suddenly addresses us as readers at the beginning of Chapter 8. Not directly, but through the use of "we".

Dunia had been with her: she had come in the morning, remembering Svidrigailov's words of the day before, that 'Sonia knows it all'. We will not go into all the details of the women's conversation, and their tears, and what close friends they became.

Until this point in the novel, the narrator’s personality remained hidden. The story was told from a detached third-person perspective, giving no indication that the narrator was a witness to the events.

Why do you think Dostoevsky did this? There's no definitive answer to this question. But there's a theory that by the end of the novel, Dostoevsky wants to make the reader a witness and direct participant in Rodion's fate. He encourages us to engage more deeply and deliver our own verdict on Raskolnikov.

This is particularly interesting considering that Dostoevsky deliberately set all the novel's events before the judicial reform that would have had Rodion tried by a jury. In 1865, there were no juries, and sentences were handed down in the old way, by a judge alone. But in this novel, we are the jury.

I congratulate everyone on this great achievement - we have finished reading the main plot of the novel. Next week will be the final article about the novel. Have a great weekend and happy holidays!

Каялся-то добрый молодец сырой земле.

Как сырой земле да сырой матери:

А прости, прости ты, матушка сыра земля,

А прости-прости, сыра матери.

И меня прости, пока да добра, молодна.

Уж я ездил, добрый молодец, да по чисту полю,

Я убил в чистом поле купца, гостя торгового…

'nothing' in Latin

Your essays atre so full of illumination, that I have to take a couple of days to rethink what we read all over again. Would it be permissible to print everything you have used to guide us, so that when I reread this novel I can refer to them before each section? Until I think for a while……Ciao

A reread is definitely in order. This book is very dense, and like an onion needs to be peeled back by layers (that’s a terrible analogy, I never cut onions like that 😂). I wasn’t sure what I expected at the outset but things kept taking darker and darker turns. Now that the plot is out of the way I can focus more on the characters’ motivations. (It’s also interesting since I listened to some chapters and read others, that the listening the first time is good for plot and language style because it is more performative, but the reading allows for more reflection.) I’m sure I’ll refer back to your commentary as well. Thanks for the introduction to an author who was previously not on my shortlist to get to.