6.6 What the devil—that might even be a mouse!

The "devil's" chapter - it's not for nothing that it's 6.6 - practically "the number of the beast," whether it's 666 or 616. This is the most mystical chapter of the novel.

Hello everyone!

I want to warn you upfront that this article, like the chapter it discusses, deals with some difficult topics. These themes are essential for understanding the novel, as Dostoevsky never shies away from challenging his readers.

List of articles by chapters you can find here

Reading schedule is here.

Today we'll explore the novel's most mystical and metaphorical chapter—Svidrigailov's final day. After an intense confrontation with Dunya, during which she nearly shoots him, he comes to the crushing realization that life without her holds no meaning.

Left alone, he picks up the revolver Dunya dropped "with a smile of despair," noting its single remaining bullet, and departs. He visits Sonya to perform one last act of charity: he hands over the receipts for arrangements made for Katerina Ivanovna's children, along with their allocated funds. He then gives her three thousand rubles, explaining that the money will be needed if Raskolnikov "takes the Vladimir Road"—the route from Moscow to Vladimir that marked the first stage of the journey east to Siberian labor camps.

After distributing his remaining wealth to his supposed young fiancée's parents, Svidrigailov wanders through Petersburg's seedy taverns. Like Raskolnikov before him, he gazes into the Neva's dark waters, clearly contemplating this means of farewell. But instead, he crosses the river.

“Meanwhile, on the stroke of midnight, Svidrigailov crossed —— Bridge to the Petersburg Side. The rain had stopped, but there was still a howling wind. ”

This is a pivotal moment—here Dostoevsky shows us that Svidrigailov, by crossing the river, enters a metaphorical realm that becomes either his dream state or perhaps his personal hell. In this space, he experiences his final visions and thoughts before his death. Let's examine this more closely.

Why does he need a bride?

If Dunya's rejection wounded Svidrigailov so deeply that life lost all meaning, why maintain this "backup" bride option? Had Dunya agreed to flee with him, he couldn't have "married" this other girl anyway. If her rejection was truly fatal to his spirit, this marriage arrangement makes no logical sense.

This inconsistency points to Svidrigailov's involvement in human trafficking with Resslich. Upon moving in with her, he likely continued their established operation. The scheme appears straightforward: Resslich identifies young brides with naive parents eager to marry their daughters to wealthy men. These parents, caring nothing for the suitor's background or intentions, allow their daughters to be married at sixteen—the legal minimum age. After the marriage, the "husband" vanishes, leaving the young wife trapped—unable to divorce or annul the marriage. In their desperation, most girls turn to Resslich, who convinces them that prostitution is their only means of survival. This is how she builds her brothel.

Before his death, Svidrigailov chose to "release" this particular girl, instructing her family to keep this from Resslich. While the parents may still seek another marriage arrangement for her, his final act of freeing at least one girl is noteworthy.

Why is the rain so important?

In the novel's calendar, it is the night of July 20th. According to the old style calendar, this is St. Elijah's Day. And Dostoevsky didn't choose this date by accident. It represents a kind of transition. According to ancient custom, this day marked the beginning of autumn.

The calendar is very important for the novel. Although Dostoevsky doesn't explicitly state dates, his days are carefully counted and maintain their Orthodox significance. I want to discuss this in more detail in the epilogues, so we can look at the entire calendar as a whole.

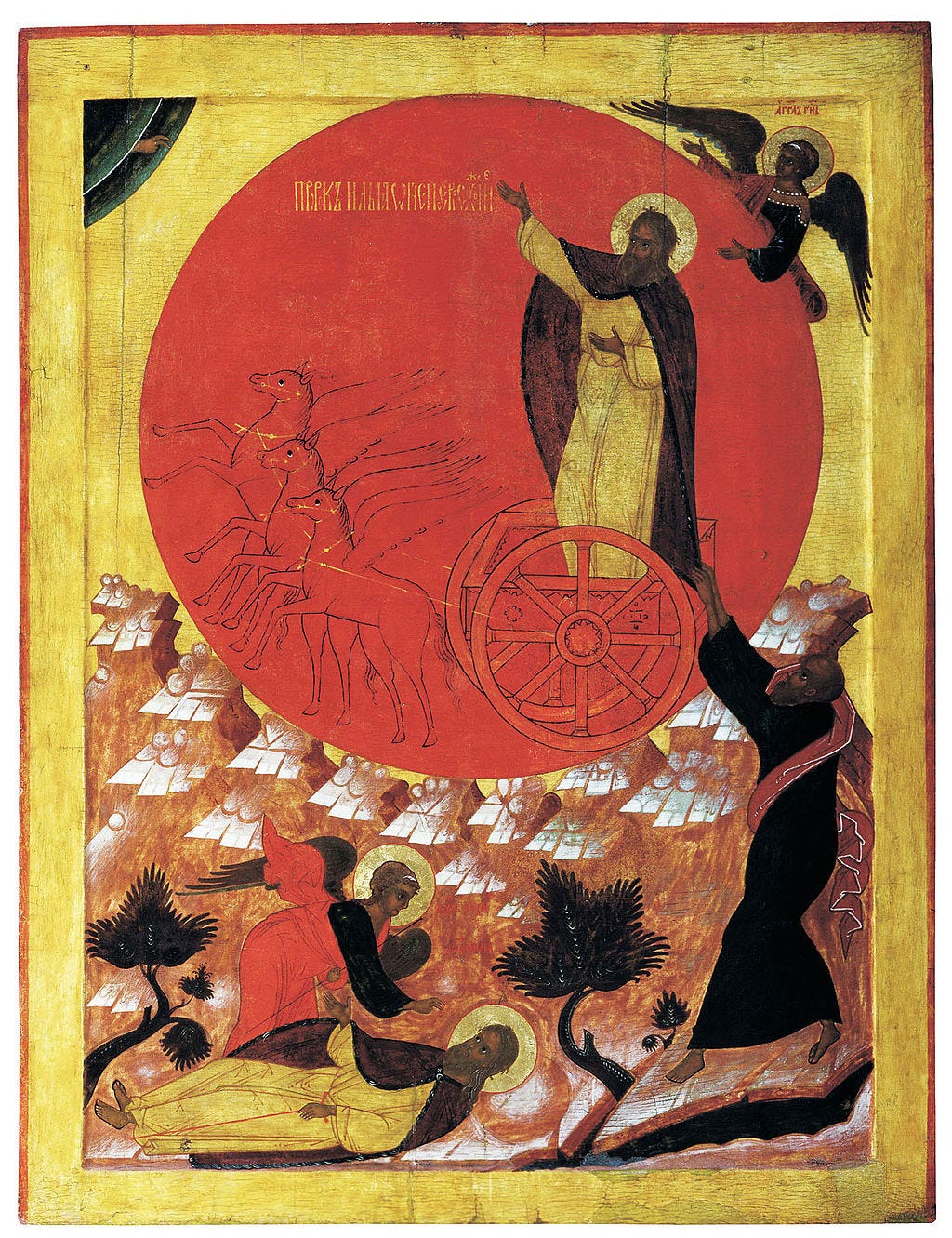

According to some researchers, before Russia's adoption of Christianity, this was celebrated as Perun's Day, which later became known as St. Elijah's Day, incorporating many pre-Christian traditions. The image of Prophet Elijah, thanks to similar functions, naturally replaced the thunderer Perun, who, according to Procopius of Caesarea, was worshipped by ancient Slavs. The notion that Elijah rides across the sky in a chariot, thundering and throwing lightning while pursuing evil spirits, is not exclusively Slavic.

Elijah is a "fearsome saint." Slavs believed that on Elijah's Day, all evil spirits, trying to escape the saint's fiery arrows, transform into various animals—hares, foxes, wolves, cats, dogs, and other creatures. This, by the way, is also worth noting. Why does Svidrigailov think the devil in the hotel is a mouse? It's precisely because he too is hiding from Saint Elijah. And Svidrigailov himself has "transformed" into a spider from his conception of "eternity"—a bathhouse with spiders. And like a spider, he tries to catch his prey in the wooden hotel—the bathhouse.

Let's recall the quote about the crossing again:

Meanwhile, on the stroke of midnight, Svidrigailov crossed —— Bridge to the Petersburg Side. The rain had stopped, but there was still a howling wind.

As soon as Svidrigailov entered the metaphysical world—his purgatory, his dream, his "eternity"—this rain stopped, although it will be said later that it rained all night. And Raskolnikov walked under it. And for Svidrigailov, the cold began—he's endlessly freezing. And this is a white night in hot July. Don't forget that during the day it's sweltering hot. At night in a city like Petersburg, it simply cannot be that cold after such heat.

The Crossing

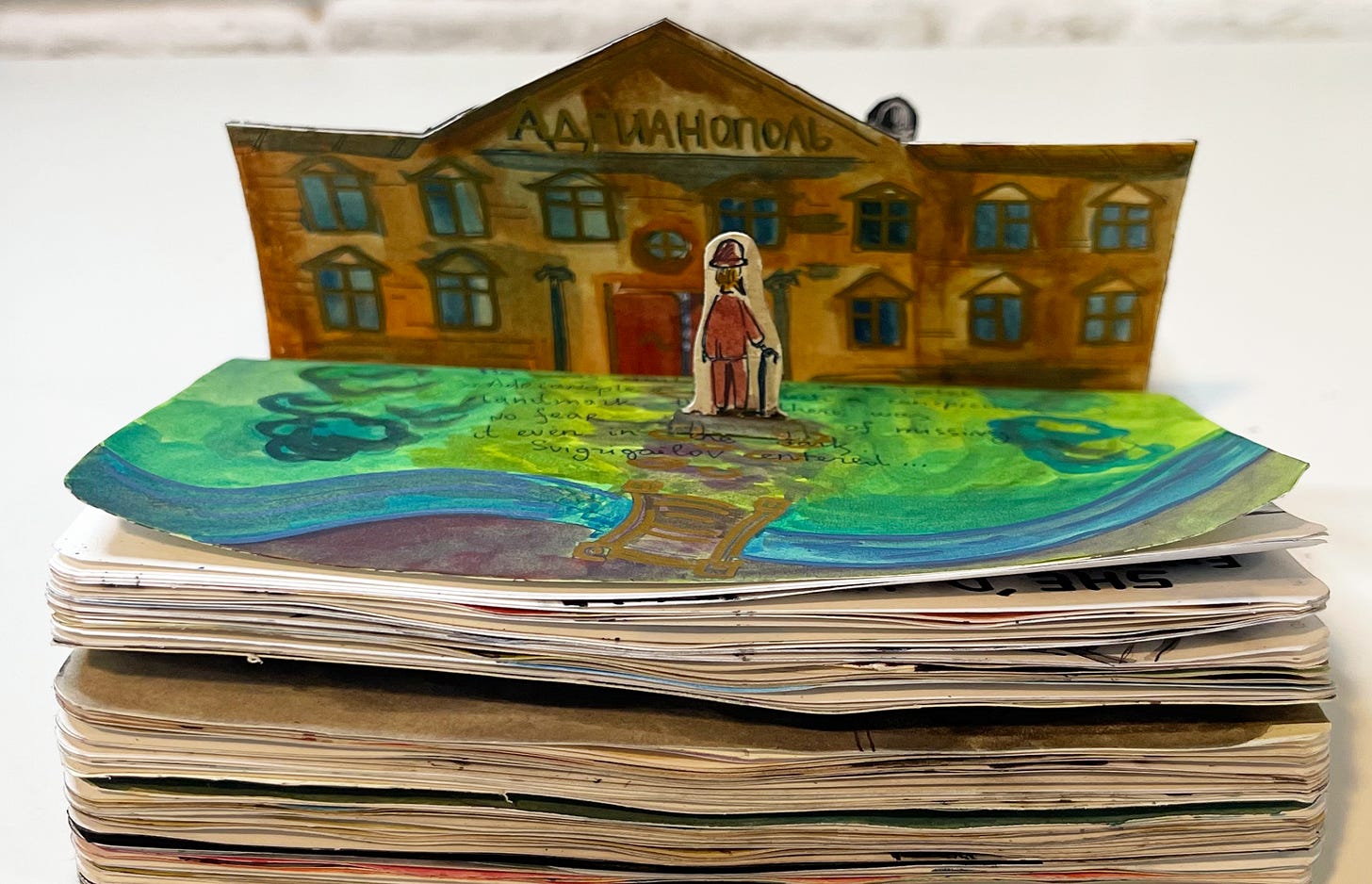

The Adrianopol Hotel is entirely fictional—no such establishment existed in Petersburg. This makes perfect sense, as in Svidrigailov's metaphysical journey, the hotel either manifests purely in his dream or exists within the "otherworldly," pagan, mystical version of Petersburg.

This otherworldly space resembles the Upside Down in "Stranger Things" or the mysterious Black Lodge in "Twin Peaks"—realms that, while no longer part of the real world, remain connected to it and mirror its contours. As in fairy tales, when Svidrigailov crosses the river or circles around (like walking around a magical hut on chicken legs), he finds himself on the "other side" of the city, in a realm of the unknown and terrifying.

The name "Adrianopol" carries similar symbolism to the surname of Sonya's landlords, the Kapernaumovs. It refers to a city in ancient Thrace (modern Turkey) that Emperor Hadrian founded in the 2nd century. Hadrian, known for persecuting Christians, was a devoted follower of paganism.

Dunya shares characteristics with Saints Agatha and Theodulia, as mentioned earlier. In a striking parallel, Saint Theodulia performed one of her miracles in the temple of the deified Emperor Hadrian. She toppled the pagan idol with merely a glance. The saints' lives describe this moment:

"Upon entering this temple, the saint saw Hadrian's idol and, after praying to the True God, breathed on the idol, and it immediately fell as if struck by thunder and broke into three parts."

Hadrian himself presents a fascinating paradox—a ruler so cruel he "poured blood like champagne," yet became venerated as an idol. This transformation perfectly exemplifies Raskolnikov's theory about extraordinary men.

This explains why the "pagan" hotel exists only in Svidrigailov's pagan version of Petersburg. His suicide ultimately reveals the futility of the pagan worldview—its fundamental impossibility as a way of life. In the hotel, Svidrigailov receives a "stuffy and cramped" room under the stairs, complete with the same yellow wallpaper.

This echoes Romans 2:9: "Tribulation and anguish upon every soul of man that doeth evil." Though the hotel seems deserted and quiet, no other rooms are available—symbolizing how Svidrigailov has lost all freedom of choice.

A Dream Within a Dream

Here Dostoevsky employs Gogolian stylistics—in "The Portrait," Gogol depicted Chartkov's famous dream where he descends through successive dreams into his own abyss, like a Russian nesting doll of nightmares. Though Svidrigailov's dream sequence is simpler, the boundaries between dreams blur until it becomes impossible to determine when he truly awakens. Traditional belief holds that visions at the threshold between sleep and wakefulness are the work of dark forces. The dream becomes a mirror where Svidrigailov sees his reflection in another's consciousness. Raskolnikov experienced something similar when he dreamed of returning to the old woman's house, finding himself unable to kill her again despite his desperate desire, while everyone around him erupted in endless laughter.

The room's "leathery" smell evokes humanity's fall, when God clothed Adam and Eve in "garments of skin" (Genesis 3:21)—a reminder that mortality is the price of sin and disobedience. Like all fallen souls, Svidrigailov cannot truly awaken but exists in a sleepwalker's haze.

In his second dream, Svidrigailov encounters a church coffin containing a suicide victim—a girl with a "violated and insulted angelic soul." Dreams never mirror reality exactly, instead transforming it through the subconscious. This vision reveals Svidrigailov's deep guilt and his wish to ease the girl's afterlife, though in reality, the church denied funeral rites to suicides. Luzhin had mentioned this(?) girl before—a deaf-mute at Resslich's who hanged herself in the attic after Svidrigailov violated her. Was she unique, or one of many fourteen-year-olds destroyed by their trafficking scheme?

Seemingly awakening yet still dreaming, Svidrigailov enters his third vision—finding a pale, exhausted five-year-old girl in the hotel corridor. After putting her to bed and approaching to check on her, he meets instead a courtesan's lustful gaze and smile, followed by "unmistakable laughter"—echoing the mocking crowd from Raskolnikov's dream.

Thus the evil forces that ruled his life, perverting every good impulse, mock him one final time—a revenge from all the female souls he corrupted.

Svidrigailov's dreams follow a clear progression of depravity:

the first dream with the mouse merely hints at corruption through vague sensations of slickness and revulsion;

the second reveals depravity's victim in the drowned girl;

the third presents ultimate corruption—a five-year-old transformed into a figure of pure depravity. When she attempts to seduce him, even Svidrigailov, despite his own wickedness, recoils in horror.

“Here is not place!”

Waking in horror and realizing what lies at the bottom of his soul, Svidrigailov leaves the hotel. He can no longer fully return to reality—he has already entered this pagan, metaphysical, inverted world. He is no longer alive.

In this world, a terrible frost grips July as he walks through deserted streets at dawn. Along the way, he encounters only one man—deathly drunk, lying face down across the sidewalk. He reaches a house with a fire tower—a tall structure used to watch for fires—where a Jewish fireman stands guard "wearing a copper Achilles-like helmet" resembling those of ancient Greece.

Svidrigailov decides this is the most suitable place for what he has planned. The fireman barely tries to stop him, only repeating in broken language, "This is not the place."

Achilles is one of the heroes of Ancient Greece, a character from Homer's Iliad. The fireman's helmet resembles Achilles' helmet as typically depicted in paintings of that time. A striking contrast emerges: "a small man"—Achilles. Some literary scholars see this as an echo of Dostoevsky's views on the Jewish people: "humanity's final word about this great tribe is still ahead"; Jews lived and continue to live by their faith in God, which has enabled them to survive many powerful civilizations throughout history.

It's significant that Svidrigailov commits suicide before a Jew. The mythological motif of the Wandering Jew emerges here. The very essence and origin of the Jews becomes crucial—Svidrigailov is deeply disturbed by the idea of eternity or immortality as endless repetition. He rebels against the eternal step in place, against eternal return. His encounter with the Jew at the very end embodies this protest. The fireman merely tells him "Here is not place"—not a place to die, not a place for rebellion against life's inevitable laws. He makes no attempt to stop him or call for help.

Svidrigailov draws his revolver with the single bullet remaining after Dunya's shots and shoots himself in the temple—precisely where Dunya had failed to hit.

What distinguishes Raskolnikov from Svidrigailov?

On St. Elijah's Night, both Svidrigailov and Raskolnikov walk in the rain contemplating suicide. At the beginning of the next chapter, we learn that Raskolnikov's clothes are dirty from walking in the rain all night. Dostoevsky doesn't describe these wanderings—instead, we follow Svidrigailov's final hours. The same fate could have befallen Raskolnikov, but didn't. Why? Because despite being a murderer and sinner, Raskolnikov still possessed faith. This faith, along with the subconscious possibility of resurrection, helped him survive this "diabolical" night. The devil could not claim his soul. Sonya was able to rekindle this faith within him. One might say that love saved Raskolnikov—not because he himself loved, but because others loved him sincerely.

Svidrigailov lacked this saving grace. Dunya's rejection denied him the spiritual salvation that Sonya offered Rodion.

Even Svidrigailov's final good deeds brought him no solace. For Dostoevsky, children represent the divine on earth—symbols of purity and salvation. That Svidrigailov, on his last day, helped care for Katerina Ivanovna's three orphans and Sonya—the entire Marmeladov family—might slightly mitigate his fate. Yet it's tragic that sinful adults emerge from innocent children. Few retain their inner purity. Dostoevsky would later attempt to portray such an adult-child in "The Idiot" through Prince Myshkin.

When Svidrigailov visits Sonya, the Kapernaumov children who were with her "run away in indescribable horror." Something in his appearance terrified them—a sign that redemption was beyond his reach.

I hope you found value in this chapter, despite its dark themes. Next time, we'll explore the final two chapters of the main plot—6.7 and 6.8—where we'll discover Raskolnikov's choice. Then we'll examine the much-debated epilogue. It promises to be fascinating.

Wow! What an incredibly insightful analysis of this section—thank you so much, Dana. What stands out to me most in these last few chapters—and really throughout the entire novel—is how profoundly complex these characters are. We often encounter characters who have shades of good and evil, but rarely are their depths explored as thoroughly as they are in this work. How does a writer manage to do that so convincingly? I can’t think about any of our main characters without feeling deeply conflicted emotions about them.

The comparison you’ve drawn between Raskolnikov and Svidrigailov is fascinating. When I reread the novel, I think I might focus primarily on the role of faith in various characters’ lives. There’s so much to explore—Raskolnikov and Svidrigailov, Sonia and Dunya, Sonia and her father, Raskolnikov and Dunya… so many intriguing lenses to consider.

Your essay gave great depth to this section. Thank you.