5.3 ‘Thief! Out from the house! Police, police!’

This chapter presents a prototype of a court. Luzhin acts as the prosecutor, while Lebeziatnikov serves as the witness, Raskolnikov takes on the role of the lawyer

Hello, Dostoevsky enthusiast!

List of articles by chapters you can find here

Reading schedule is here.

This chapter unfolds like a small theatrical performance or a court scene, despite the fact that courts in the Russian Empire at that time had neither witnesses, lawyers, nor prosecutors. Back then, sentences were generally passed based solely on police information, without appeals or defense—an immediate court decision.

This chapter presents a prototype of a court. Luzhin acts as the prosecutor, while Lebeziatnikov serves as the witness who doesn't grasp Luzhin's motives. Raskolnikov takes on the role of the lawyer, putting everything in its place. The wake attendees, representing various social strata, function as a peculiar jury, passing judgment on Luzhin and effectively "expelling" him. Although Luzhin escapes punishment for his slander, fraud, and the moral trauma inflicted on Sonia, this can still be considered a victory. We hear no more of Luzhin in the novel; he departs, defeated, in an unknown direction. Dunya is now free from his influence.

Luzhin's Accusation

It's interesting to note several details about how Luzhin arrives and begins to speak about Sonia's actions. He deliberately uses the wrong patronymic for her. He calls her Sofya Ivanovna, even though he knows her correct patronymic perfectly well, as we understand later. After he begins to doubt his actions, when he sees the effect it has on the widow, he immediately uses her name correctly — Sofya Semyonovna.

And what kind of scoundrel does one have to be to come to the wake for Sonia's father — Semyon, and deliberately use the wrong patronymic, i.e., incorrectly state the name of the deceased.

He also gets confused about the amount of money he had. Let's count:

"This morning, for my own purposes, I exchanged several five-percent bonds for a sum of, nominally, three thousand rubles. The calculation is recorded in my wallet. Upon returning home, I — Andrei Semyonovich is witness to this — began to count the money and, having counted two thousand three hundred rubles, put them in my wallet, and the wallet in the side pocket of my frock coat. About five hundred rubles remained on the table in banknotes, and among them three hundred-ruble notes."

So, he had 3000 rubles. He counted 2300, which he hid. On the table were 500 rubles and 3 bills of 100 rubles each — 300 rubles. In total, 3100 rubles. But neither he nor the visitors pay attention to this, because they generally don't understand what he wants to convey to the visitors with these huge sums, who earn about 100-200 rubles a year. And in his own speech, he says that he couldn't come to the wake. But here he is! Here at the wake, he came specially, and he's ruining it! What a despicable man!

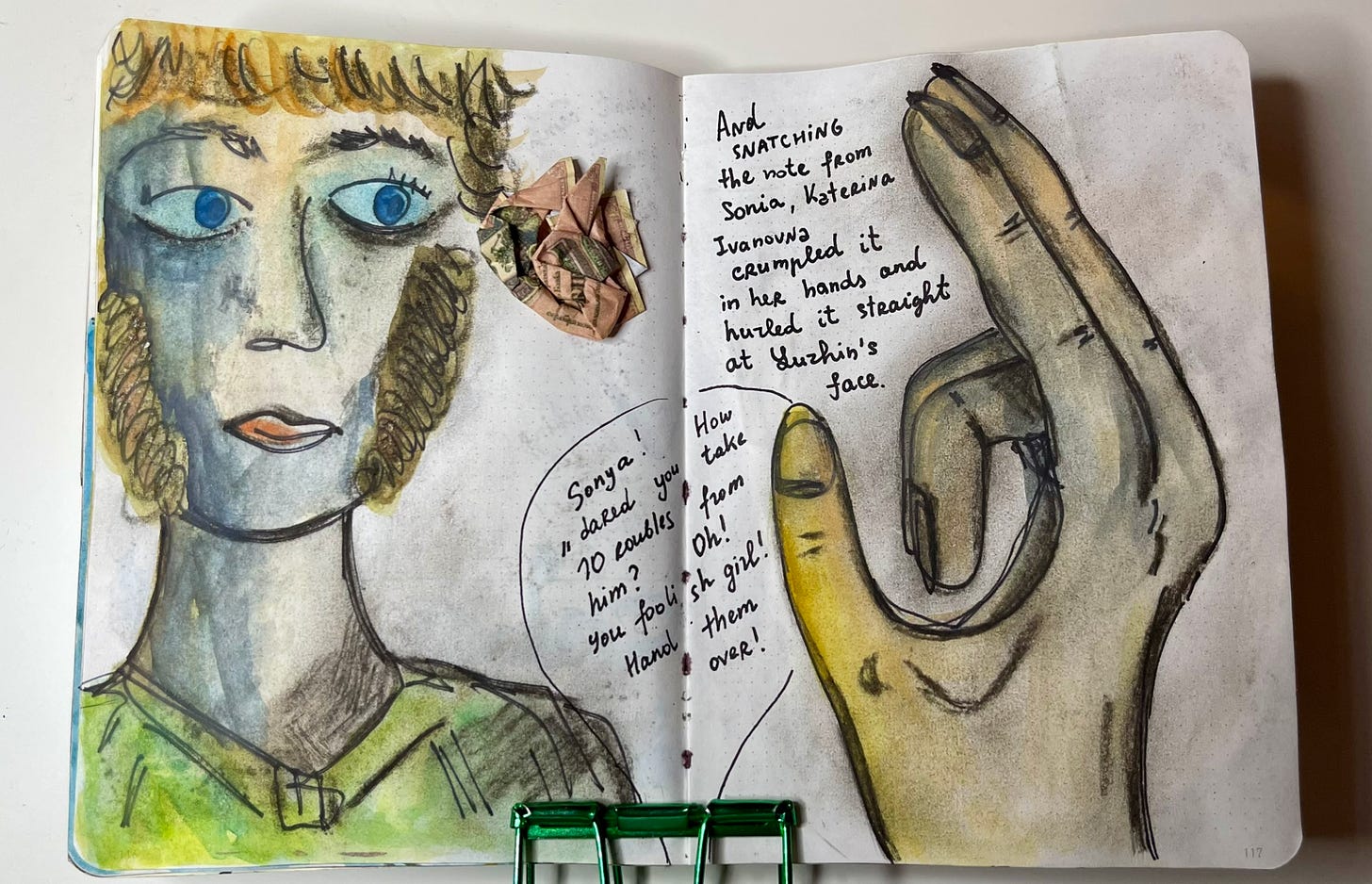

Katerina Ivanovna immediately sees right through him. And she says that he's a fool and a petty court official. That is, a corrupt, cunning bureaucrat. She throws at him the 10 rubles given as "charity" to her family.

Lebeziatnikov's Testimony

Although Lebeziatnikov's character is not portrayed as the most pleasant person in the novel, Luzhin's behavior is intolerable to him. He chooses to tell the truth, even though he could have covered for his friend (patron). But I think this contradicts his principles, which are based on honesty and straightforwardness. He certainly has some strange ideas about the future and life, but it's clear that he doesn't tolerate lies. That's why he immediately says he would take an oath in court. And what does that mean? Back then, one had to give "a sworn promise, usually accompanied by kissing the cross".

And he recounts how he saw Luzhin quietly slip a folded piece of paper into Sonya’s right pocket. Why didn't he say anything about it right away? He thought Luzhin was doing a good deed, genuinely wanting to give Sonia this money, but not wanting him or Sonia to see it. Probably even for Lebeziatnikov, this is too much.

"that you wanted to avoid gratitude and, well, how is it said: so that the right hand doesn't know... in a word, something like that"

Lebeziatnikov vainly tries to recall Christ's words from the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 6:3-4).

"But when you give to the needy, do not let your left hand know what your right hand is doing, so that your giving may be in secret"...

In general, although Lebeziatnikov denies these acts of charity, he remembered this motif from the Bible. However, Luzhin desecrated this motif.

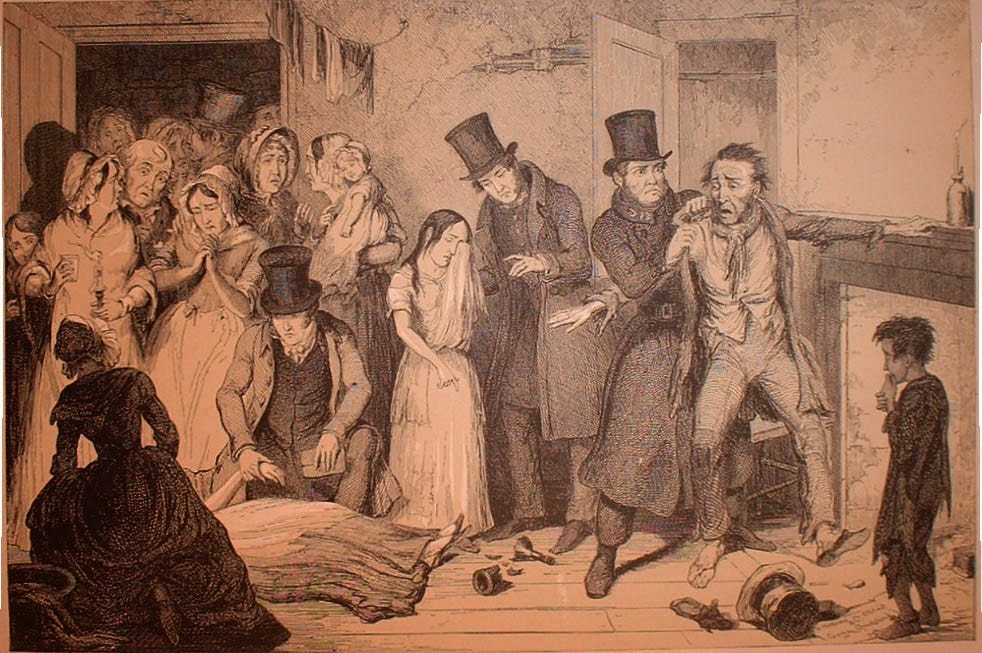

This plot of planting money was borrowed or inspired by Dostoevsky from Charles Dickens' "The Old Curiosity Shop". Overall, the image of the Marmeladov family resembles the poor from that England described by Dickens. Poverty was roughly the same back then. In Dickens' novel, the lawyer Brass, which also relates him to Luzhin, who also works in this field, slips money into the hat of a boy named Kit. Also to later accuse him of theft.

I want to show you a series of works by illustrator George Cruikshank that reminds me of the Marmeladovs. It's not surprising, as it's from the series The Drunkard's Progress — The Evil Road of Drink. Overall, the illustrations depict a similar story in England to what unfolds in 19th century St. Petersburg. Everywhere, poverty and alcoholism have similar endings.

Raskolnikov the Lawyer

If you remember, Raskolnikov was studying to be a lawyer, and could potentially have worked as an advocate in the future. It was in 1866 that they appeared, and universities even introduced "oratory" specifically for lawyers. Raskolnikov didn't have this subject, but nevertheless, he was able to logically and quite confidently piece together what had happened and why Luzhin needed all of this.

If Luzhin's plan had succeeded, he could have sent her to prison. But it seems that even after the banknote flew out of the right pocket during the search, he immediately regretted what he had done and wanted to leave. Probably, his desire was only to demonstrate this, so that he could write another letter to Dunya later. But who knows how this would have affected Sonya.

We see that for her, this is an enormous stress.

"But at first, it became too heavy. Despite her triumph and her vindication — when the initial fear and stupor passed, when she understood and grasped everything clearly — a feeling of helplessness and hurt painfully constricted her heart."

Indeed, how could she have defended herself? She couldn't. Alas, she was poor and powerless. As before Lebeziatnikov began to speak, the crowd wanted to lynch her. In general, people's justice was always merciless. If not prison, then she would have been unjustly persecuted by the people around her. As it almost happened with Dunya. Remember that story from the mother's letter about Svidrigailov and his wife? How easily they ruined her reputation?

Sonya couldn't bear it and ran out of the room.

The Motif of Departure

The funeral feast descended into chaos as the mourners refused to calm down. The scandal escalated into a tragedy: people hurled objects, some burst into song, while others shouted. Amidst the tumult, the poor children huddled fearfully on a trunk. It's at this moment that Katerina Ivanovna takes her leave—a departure not merely from her relatives, home, and children, but a symbolic exit in search of truth and justice on the streets.

This motif of departure isn't novel in Russian literature. Pushkin employed it in his 1835 poem "The Wanderer," («Странник») where the protagonist, "like a blind man freed from a cataract by a physician," glimpses a certain light and hastens to abandon his city, home, wife, and children. Yet the masses, steeped in age-old lies, are reluctant to release this seeker of truth—a man they deem mad:

Some were already chasing me; — but I all the more

Hurried to cross the city field,

To see sooner, leaving those places,

The sure path of salvation and the narrow gate.(This is not a literary translation)1

It's no surprise that Leo Tolstoy was captivated by the legend of Emperor Alexander I's disappearance, who allegedly resurfaced as the elder Fyodor Kuzmich. Ultimately, Tolstoy enacted this theme in his own life, leaving his ancestral home in his final hours to wander aimlessly. His reasons for departing and what he sought remain shrouded in mystery.

Katerina Ivanovna's exit wasn't merely due to her impending eviction—the quarrel with Amalia Ivanovna could have been resolved, as it had been before. Rather, this confrontation served as a catalyst for Katerina Ivanovna's departure. A multitude of grievances had accumulated. In her mind, this was the culmination of her dispute with a cruel and unjust God.

"Lord!" she suddenly cried out, her eyes flashing, "is there really no justice! Whom should You protect if not us orphans? Well, we shall see! — there is justice and truth in the world, there is, I will find it!"

She ran off in search of truth. Meanwhile, in the Marmeladovs' passageway, an unprecedented and unheard-of outrage was taking place.

And Raskolnikov set off to see Sonia.

Tell me, what are your impressions of the chapter and of Luzhin's action? What do you think will happen to Katerina Ivanovna and her children?

Happy reading!

Original:

Иные уж за мной гнались; — но я тем боле

Спешил перебежать городовое поле,

Дабы скорей узреть, оставя те места,

Спасенья верный путь и тесные врата.

This book is starting to mess with my mind. I find myself more enraged at a man for framing a girl for petty theft than I am at a man who brutally murdered two humans. We’re really traversing all the circles of hell in this one.

This chapter gave me a headache! The yelling, drinking, arguing, throwing objects, cheating the vulnerable, neglected orphans, It was humanity about its worst, and all this at a funeral. Now that we have been willingly led to this baseness, I need Dostoevsky to pull us back to something softer in humanity.