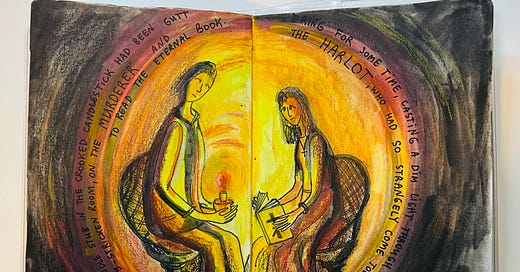

4.4 …the murderer and the harlot, who had so strangely come together to read the eternal book

Raskolnikov comes to Sonya, they read the parable of Lazarus' resurrection. He promises to tell her who killed Lizaveta. But someone else is eavesdropping on all of this...

Hello, Dostoevsky enthusiast!

List of articles by chapters you can find here

Reading schedule is here.

Raskolnikov perceives himself victorious in his initial encounter with Porfiry and dismisses Svidrigailov arrogantly. Yet, a tradesman's sudden accusation of murder once again throws him off balance. After orchestrating Dunya's separation from Luzhin during a family gathering, Raskolnikov temporarily cuts ties with his family.

Despite his repeated pleas for solitude—"Leave me alone!"—Raskolnikov finds isolation unbearable. The inability to discuss his crime torments him.

Fulfilling an intention born during his conversation with Marmeladov, Raskolnikov visits Sonya. He reasons that they're similar—he killed others, she killed herself. Her prostitution, chosen to save her family from starvation, is a mortal sin leading to eternal damnation. They have both violated society's laws and norms; she should understand him.

Raskolnikov proposes that he and Sonya join forces to achieve "power and dominion" over "all trembling creatures," over "the entire anthill." He imagines them as "supermen," heroes and benefactors of humanity. In his mind, they both committed crimes for the greater good.

However, Raskolnikov fails to grasp two crucial points:

There's a fundamental difference between self-sacrifice and sacrificing others, regardless of the goal;

Unlike Raskolnikov, Sonya doesn't justify her actions with lofty ideals of self-sacrifice or superiority. Instead, she views herself as a great sinner, placing all her hope in God and clinging to the Gospel.

Sonya, despite her gentle nature and limited education, effortlessly unravels Raskolnikov's complex self-justifications. Their encounters prove pivotal in Raskolnikov's journey, revealing his inner struggle and gradual path to redemption.

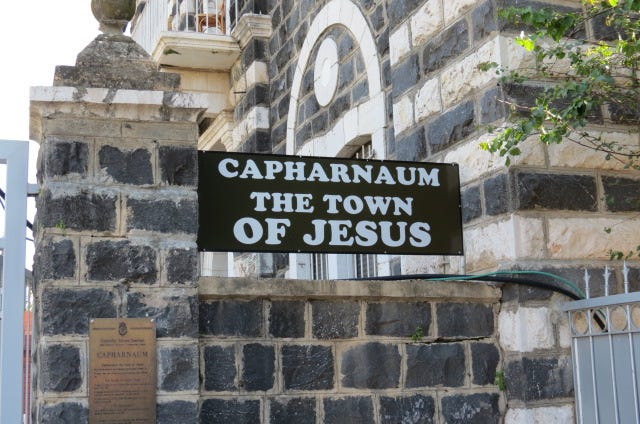

Is Kapernaumov's flat symbolic of Christ's presence?

*As he was wandering about in the dark, wondering where the entrance to Kapernaumov’s flat might be, a door suddenly opened three paces away. Instinctively he took hold of it.

‘Who’s there?’ asked a frightened female voice.*

The surname of the family where Sonya rents a room is not at all accidental. It's a reference to Christ's city - Capernaum.

After leaving Nazareth, Jesus settled in Capernaum by the sea. Here, He declared, "I have come to call not the righteous but sinners to repentance," and performed numerous healing miracles—acts He couldn't do in Nazareth due to the inhabitants' unbelief. Indeed, "most of His mighty works were done" in Capernaum (Gospel of Matthew, 4:13; 9:1; 9:13; 9:18-25; 11:20).

Yet Christ also admonished Capernaum's residents against pride, warning, "And you, Capernaum, will you be exalted to heaven? You will be brought down to Hades" (Gospel of Matthew, 11:23).

Curiously, in late 19th-century Russia, "capernaums" became a term for taverns and drinking establishments. This nickname, inspired by Christ's city, gained popularity due to a renowned café called "Capernaum." More than just a drinking spot, it served as a hub for intellectual discourse and writers' gatherings. The café stood next door to one of Dostoevsky's former residences—now his museum-apartment—at the intersection of Kuznechny Lane and Vladimirsky Prospekt.

This blend of the evangelical and the tavern isn't new to the novel. Recall Marmeladov's tavern "sermon" in the second chapter—one might say they were in their own Capernaum.

The Magic of Number 4

As you've noticed, this is Chapter 4 of Part 4. And it's not by chance. This entire chapter is filled with the significance of this 4. In Orthodox numerology, the number 4 signifies universality (according to the number of cardinal directions), sometimes completeness, fullness. Likely, Dostoevsky wanted to show that this is the main, central chapter of the novel. It contains the entire meaning.

Where else number 4 lays a role? They read about the resurrection of Lazarus from the Fourth Gospel.

In the structure of the Four Gospels—the first four books of the New Testament—the first three, known as the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke), differ significantly from the fourth Gospel. According to church tradition, the fourth Gospel was written by Christ's beloved disciple, the Apostle John. The Synoptic Gospels are closely related in terms of events, with their narratives largely built on the same episodes. However, John's Gospel differs conceptually from the first three. Notably, the story of Lazarus' resurrection appears only in the fourth Gospel. In the first three Gospels, this character is absent; they only mention "a beggar named Lazarus."

And in this parable of Lazarus' resurrection, he rises on the fourth day.

Lord, by this time there is a stench, for he has been dead four days.

There's a theory that for Raskolnikov, this is also the 4th day after the murder, if we don't count his days of unconsciousness. But it doesn't quite add up there. Still, it's a beautiful theory.

It's also interesting that Sonya is the fourth child in the Marmeladov family, but three children are together from one set of parents, while she is from another. She is like the Gospel of John - both a part of the whole, yet separate.

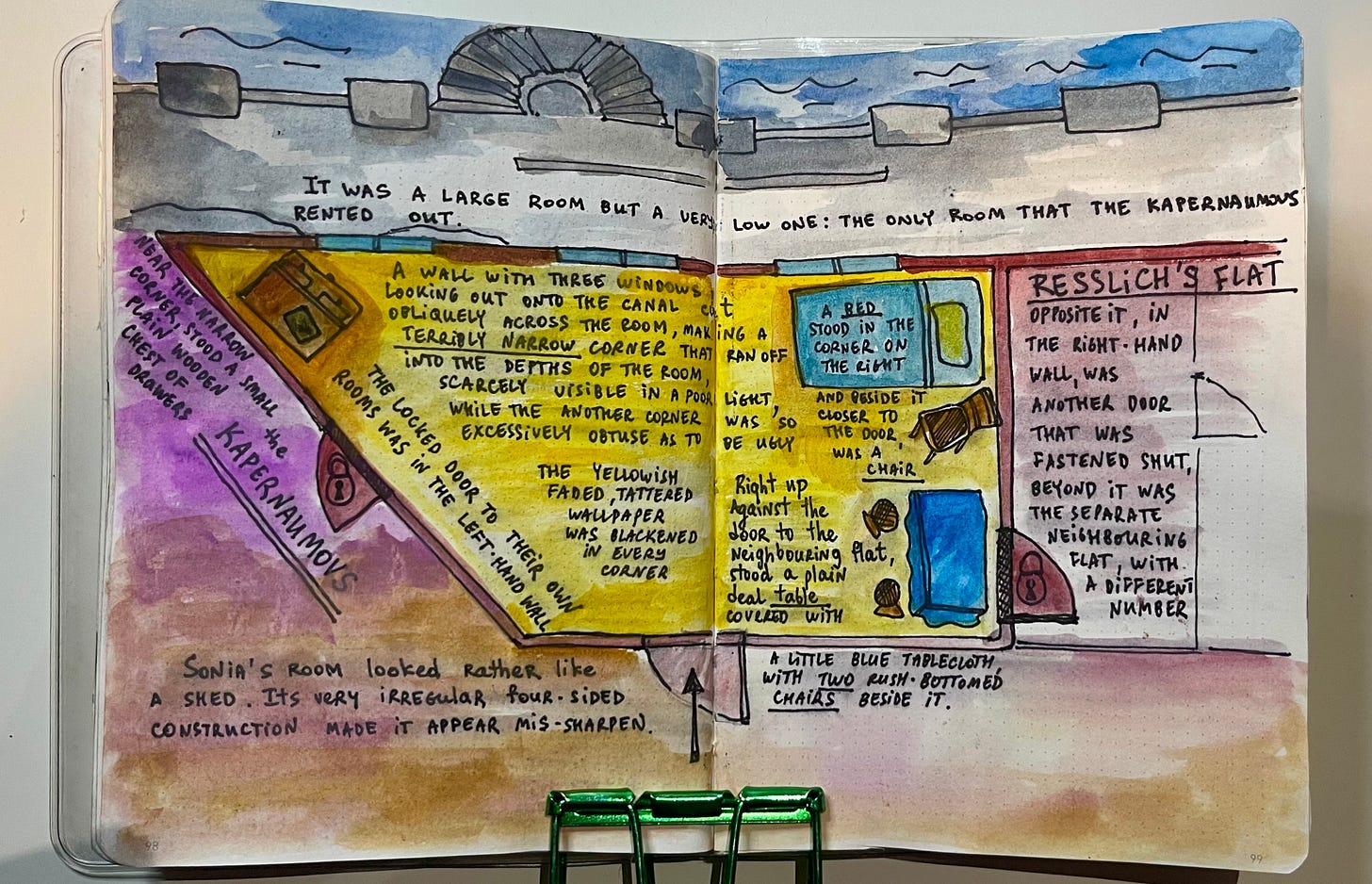

Here we can also note the strange shape of the room in which Sonya lives. We are used to rooms with right angles, and generally it's a quadrilateral figure that is harmonious and correct, but not in this case. Although, of course, the room still has 4 walls, it is not harmonious, not stable, and generally ridiculous. It lacks both architectural harmony and comfort for living and furniture arrangement. Interestingly, it is in Sonya's room that Dostoevsky describes each of the 4 corners.

The Christian Cross is also a kind of quaternity.

Perhaps you have found some other references to the number 4 in the chapter or novel? Most likely they are not accidental.

Holy fool

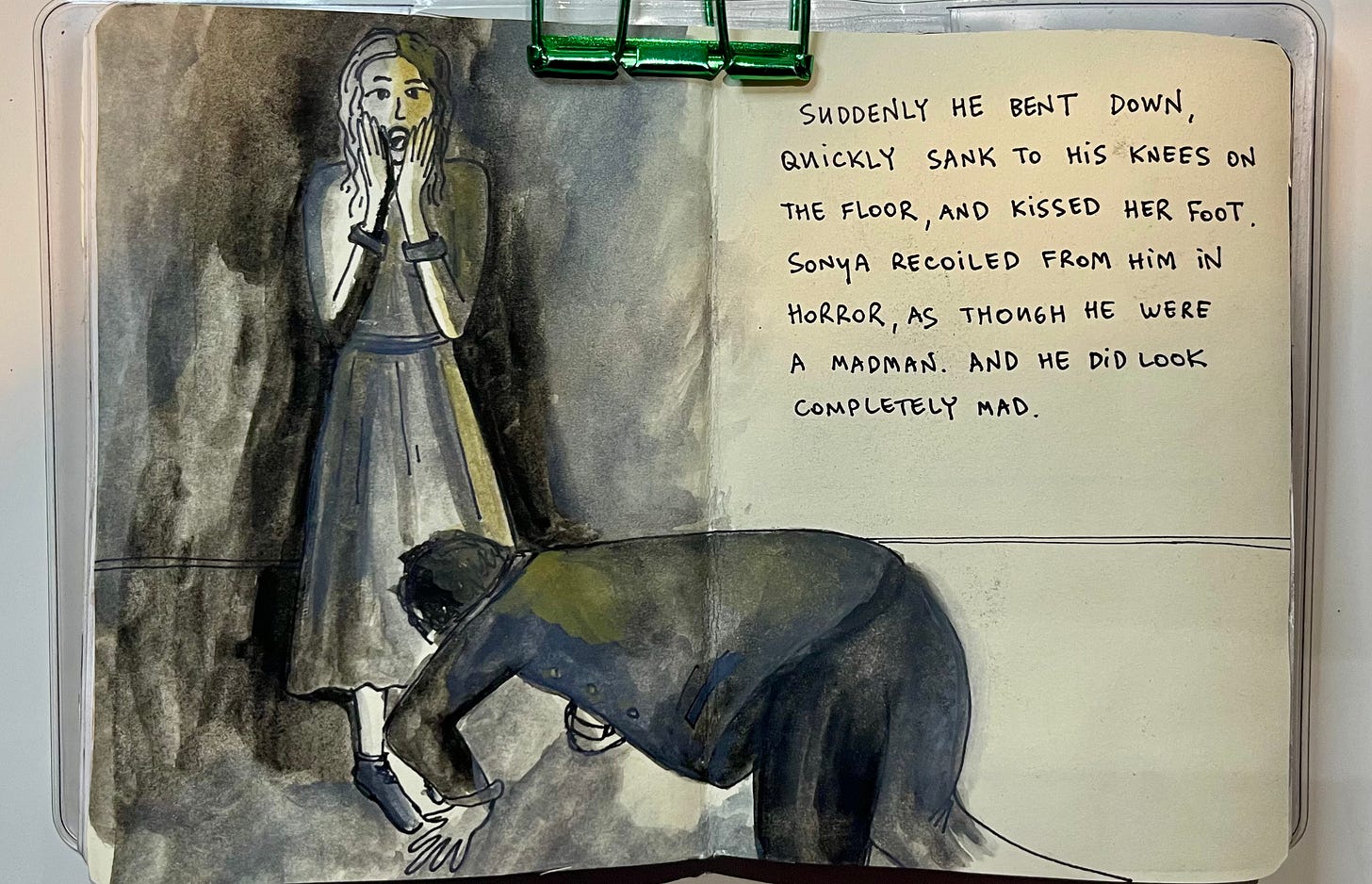

Raskolnikov behaves abominably at Sonya's, attacking the poor girl without restraint. He achieves his goal—reducing her to tears. After five minutes of tense silence, Raskolnikov approaches Sonya, bends down, and kisses her foot, declaring: "I did not bow down to you, I bowed down to all human suffering."

The ideologue in Raskolnikov still dominates his other human qualities. He eagerly seizes upon Sonya's self-description as a "great sinner," insisting that her self-imposed sin is futile—it won't secure happiness or even peace for her loved ones. In this, he sees a parallel with himself.

Sonya's worldview so starkly contrasts with Raskolnikov's that he's initially bewildered: How can this be? He settles on a comforting explanation—she must be insane. "In three weeks' time, you're welcome to the seventh verst!" (This refers to the Hospital of All the Afflicted for the mentally ill, located in the suburbs of St. Petersburg.)

The following lines are perhaps the most crucial in the novel:

"Do you pray to God often, Sonya?" Raskolnikov asks, concluding she's merely a holy fool (interpreting holy foolishness as excessive piety).

"What would I be without God?" Sonya replies.

"And what does God do for you in return?" Raskolnikov probes further.

"He does everything!" she responds quickly, lowering her gaze.

Such an answer from a girl in such dire circumstances gives even Raskolnikov pause, though he still clings to the notion that she's simply a "holy fool" ("юродивая" / yurodivaya).

Holy fool ("юродивый" / yurodivyj) — "insane, God's fool, simpleton, born mad," as defined in Dal's dictionary (the primary 19th-century Russian language reference): "The common people regard holy fools as God's people, often finding profound meaning in their unconscious actions, even premonition or foresight; the church also acknowledges those who are fools for Christ's sake, (voluntarily) adopting the humble guise of holy foolishness."

Raskolnikov uses "holy fool" to describe Sonya in its general sense — insane, mad. Yet we realize that Rodion himself is beginning to be touched by this holy foolishness. Through Sonya, he's being drawn into the fold of God's people.

Sonya's Bible or…

The book belonging to Sonya mirrors Dostoevsky's own copy of the Gospel. During his four-year imprisonment, this was his sole permitted reading material (yes, he didn't read anything else at all for 4 years!). As evidenced by his works, Dostoevsky internalized the New Testament, quoting and drawing imagery from it extensively in his fiction, journalism, and correspondence. One can only imagine the depth of his immersion in these biblical narratives.

This particular Gospel has survived and been meticulously studied. Scholars have documented every pencil mark, fingernail scratch, and folded page. All these details have been analyzed and made available to the public. Pictured here is a spread from the Gospel of John in Dostoevsky's volume, featuring the parable of Lazarus' resurrection, with all annotations carefully described.

I didn't translate the notes from these pages, as they don't contain meaningful content in themselves—they merely describe the location of markings, what they underline, and the materials used. Dostoevsky didn't write in the Gospel; he only underlined, put checkmarks, and similar annotations.

It's from these very pages that Sonya reads to Raskolnikov.

I should also mention that this chapter was censored and rewritten, causing a scandal at Katkov's publishing house. The original text of the chapter, which hasn't survived, featured the characters reading the Gospel episode about Lazarus' resurrection. However, the editorial board of "Russian Messenger" rejected it, claiming they saw "traces of nihilism" in the scene. Consequently, Dostoevsky was compelled to rework the text, giving, in his own words, "the reading of the Gospel [...] a different color".

According to a common opinion, Katkov's objections "were caused primarily by the fact that Dostoevsky put the words of the Gospel into the mouth of a 'fallen woman', making her an inspired interpreter of Christ's teachings..."

In the original version, indeed, the initiative to turn to the Gospel belonged not to Raskolnikov, but to Sonya, who ecstatically exclaimed: "Well, kiss the Gospel, well, kiss it, well, read it! (Lazarus, come forth!) <...> I myself was Lazarus dead, and Christ resurrected me"

In the final version, however, Raskolnikov chooses the "Lazarus" episode and must overcome Sonya's reluctance. She kept hesitating... Somehow she didn't dare to read to him... 'What for? You don't believe, after all...'" she whispered softly, her breath catching.

Regarding the conflict with Katkov, Dostoevsky wrote:

"Reworking the big chapter cost me at least three new chapters' worth of effort."

… or Lizaveta’s Bible

It turns out that Lizaveta, who continues to play a role in Raskolnikov's fate, brought the Gospel to Sonya shortly before her own death. This revelation astounds him. "Everything about Sonya was becoming stranger and more wondrous to him with each passing minute."

It's worth noting that Dostoevsky was the first to include such extensive Gospel quotations in a fictional, novelistic text—an unusual practice for that time. This innovative approach further highlights the uniqueness of his first great novel.

Following the Gospel reading, there's a phrase "from the author" that many critics, including the writer Vladimir Nabokov, find inappropriate.

“The candle stub in the crooked candlestick had been guttering for some time, casting a dim light through the poverty-stricken room, on the murderer and the harlot, who had so strangely come together to read the eternal book. ”

This phrase offers hope: after all, Christ forgave both the thief and the harlot—those who repented. Yet we are repeatedly reminded that a person's spiritual transformation rarely occurs instantaneously. Did Raskolnikov glean any understanding from reading the eternal book? Immediately after the Gospel reading, he broaches the "matter" with Sonya. Informing her that he has "broken" with his mother and sister, he proposes that she accompany him: "We are cursed together, so let's go together!"

Where to? He himself is unsure, knowing only that it's "along the same road." In his view, Sonya has also "crossed" the line between good and evil, has also "ruined her life—her own (it's all the same!)," and, like him, will descend into madness if left alone. Raskolnikov adds that Polechka and her younger siblings will inevitably perish, then utters phrases revealing his attitude towards faith:

“And yet children are made in Christ’s image: “Of such is the Kingdom of God.” He commanded that they should be honoured and loved, for they are the future of mankind…”

Rodion still believes in this "future of mankind," where everyone will be like children. However, he draws a startling conclusion: everything must be destroyed, once and for all. He believes one must take suffering upon oneself, seeking freedom and power—above all, power! Power over all trembling creatures and the entire anthill. That's his goal!

Unsurprisingly, Sonya fails to comprehend him.

Intriguingly, as he departs, Raskolnikov promises to reveal to Sonya who specifically killed Lizaveta—not the old woman, as the investigation had focused on until now. In this dialogue with Sonya, Lizaveta emerges as the primary victim.

The chapter ends with a surprising revelation: both this conversation and subsequent ones between Sonya and Raskolnikov are being eavesdropped on by Svidrigailov, who has positioned himself comfortably on a chair behind Sonya's wall. What else is this main "villain" of the novel's second half planning? We've seemingly dealt with Luzhin, and now another member of the devil's entourage takes center stage.

What are your thoughts on this chapter?

My main struggle with Dostoevsky is that his way of thinking is so fundamentally alien to my own. Last entry you told us to read this as a morality tale rather than a psychological investigation, and I'm TRYING to—with varying results.

I definitely appreciate what it means to choose Sonya to deliver the Gospel, especially in that time period. My heart bleeds for her, for having to deal with Raskolnikov on top of everything else. Can you imagine, having to become a parent to your own parents and siblings? Having to sell yourself in order for them not to starve? I'm so angry that she lives in a world that told her she's a sinner and not a victim. I'm so angry that everyone has failed her on such a spectacular level and religion is the only thing stopping her from plunging into desperation. There is something fundamentally wrong in a society where the poorest can either pray or go insane, where there's no help other than God's. (Which is not to say that religion is bad, although I'm not religious myself I do respect people who can find meaning in it. I'm glad Sonya has it and Rodion will have it at some point.)

Still the fact remains that she and her family will probably starve or die of consumption or end up in the streets, and while Rodion goes about it the wrong way (he chooses violence instead of being kind, to her and to others), he is not lying. He has a knack to go beyond social conventions and tell uncomfortable truths out loud. And he is so lonely, so desperate to find kinship in a world that treats him like an alien. Poor Sonya is the only person who doesn't act selfishly around him, did you notice? All the others are telling him that the way he acts upsets them, Sonya can see how truly sad he is and genuinely wants to help. She shouldn't have to, though.

I was starting to get worried about Sonya’s safety as Raskolnikov was becoming more unhinged here. At the same time, it was incredibly tragic to see these two souls in despair and poverty.

As soon as it was mentioned that the room next door was extension of Resslich’s and there wasn’t Kapernaumov family there, it gave me proper chills - Svidrigailov seems to be a very menacing and dark figure literally hiding in the shadows. I’m worried what’s to come from him…Brrr