Q&A: The History of The Brothers Karamazov

In this article, you will read about how and when Dostoevsky conceived the idea for the novel, how he executed it, how he published it, how much he earned, and how it was received.

Greetings to all Dostoevsky enthusiasts.

Link to schedule and materials for the novel.

Today, I will share some insights into the creation of the novel The Brothers Karamazov—how Dostoevsky wrote it, when it was completed, and how it was received after its publication.

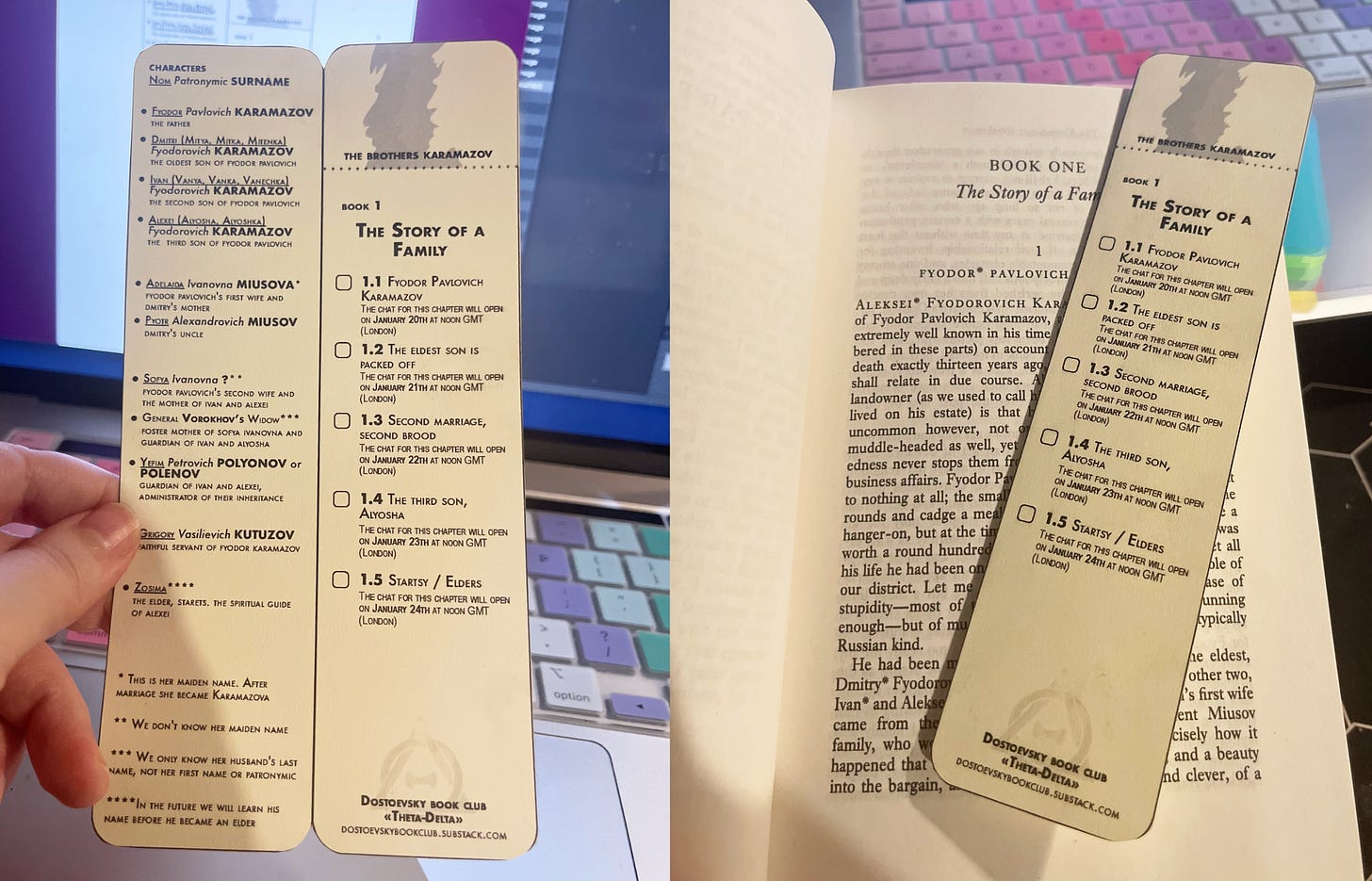

You can read about the 'Author's Foreword' in yesterday's article. For those who missed it, you can also download a bookmark for the first part—like this one.

On Friday/Saturday, there will be an important post for those struggling with Russian names. And on Monday, we'll have our first chat about the first chapter of the novel. So prepare your impressions and observations.

In his final novel, Dostoyevsky charts a path for modern society out of its ideological dead ends. It argues against what the author sees as the plagues of his century: atheism, materialism, utilitarian socialist morality, and the breakdown of the family.

The novel The Brothers Karamazov was originally conceived as the first part of 'The Life of a Great Sinner,' exploring the journey of a man who attains righteousness through temptation. The three Karamazov brothers — Dmitri, Ivan, and Alexei —debate eternal questions:

Is there immortality of the soul?

Is humanity guided by free will or merely by the laws of nature?

Do God and the Creator exist?

While simultaneously grappling with matters of love and money. As Dostoevsky wrote to Nikolai Lyubimov, his editor at The Russian Herald:

"If I succeed, I will accomplish something good: I will make people acknowledge that a pure, ideal Christian is not an abstract matter, but rather something figuratively real, possible, visibly present, and that Christianity is the only refuge for Russian Land from all its evils."

Dostoevsky had been developing the concept for his final work since the 1860s. Initially, he planned to write two novels: Atheism and The Life of a Great Sinner. These works would explore the fall and resurrection of the human soul against the backdrop of contemporary events in Russian and world history, contrasting eternal questions of good and evil, faith and unbelief with modern mindsets. However, he only managed to complete the first part of this epic work.

The Brothers Karamazov was written between April 1878 and November 1880, primarily in Staraya Russa, which largely inspired the fictional city of Skotoprigonyevsk.

While working on the early chapters of the novel in the summer of 1878, Dostoevsky experienced the devastating loss of his three-year-old son, Alexei, who died from an epileptic seizure—a condition inherited from his father. Deeply grieving his son's death, Dostoevsky, accompanied by philosopher Vladimir Solovyov, visited the Optina Monastery. There, he met with Elder Venerable Ambrose (Grenkov). Following this visit, Dostoevsky 'returned comforted and began writing the novel with inspiration'

The writer's wife, Anna Grigoryevna, believed that Elder Zosima in the novel echoes the words of Elder Ambrose when consoling a mother grieving the loss of her son. Work on the novel was delayed for various reasons, particularly due to Dostoevsky's illness, which required him to seek treatment in Ems. Approximately three months after the novel's publication was completed, the writer passed away.

The main plot of the novel—detective and melodramatic in nature, revolving around intersecting love stories and financial predicaments—is interwoven with self-contained, essentially independent works.

For example, the sixth book, The Russian Monk, includes the life story and teachings of Elder Zosima. Other self-contained sections include The Boys, Ivan Karamazov's 'poem' The Grand Inquisitor, and The Marriage at Cana. Additionally, the novel features seemingly unrelated plot elements, such as the confessions and manifestos of the characters, like Mitya Karamazov's three Confessions of an Ardent Heart ('In Verse,' 'In Anecdotes,' and finally, 'Heels Up'). The flow of the plot is constantly interrupted by theological disputes, conducted by different characters and in different registers.

The fantastic element plays a crucial role in the novel—dream sequences, hallucinations, and visions are central to its structure. Overall, the novel can only be conditionally classified as realistic. For example, Mikhail Bakhtin1 attributed the 'life-implausible and artistically unjustified' scandalous scenes that abound in The Brothers Karamazov to the specific 'carnivalesque' logic of Dostoevsky's artistic world. As Bakhtin writes:

"Carnivalization... allows the narrow scene of private life in a specific limited epoch to expand into a universally human, mystical scene."

Several sources are explicitly referenced in the novel through the characters' dialogue. These include the Old Slavonic apocrypha The Virgin Mary's Journey Through Torments and Victor Hugo's Notre-Dame de Paris. Dostoevsky had written a preface to the Russian translation of Hugo's novel in 1862, where he described its central idea as the fundamental thought underlying all nineteenth-century art:

"This is a Christian and highly moral thought, its formula being the restoration of the fallen person, unfairly crushed by the burden of circumstances, the stagnation of centuries, and social prejudices."

Les Misérables was equally significant for Dostoevsky—The Brothers Karamazov can be seen as a form of polemic with Hugo. Additionally, E. T. A. Hoffmann's works, with their fantastic and fairy-tale motifs, also played a significant role in shaping Dostoevsky's artistic vision.

It has become commonplace to compare Ivan Karamazov to Goethe's Faust and Shakespeare's Hamlet. A distinctive leitmotif in The Brothers Karamazov is a quote from Karl Moor's monologue in Schiller's The Robbers. We will discuss this further when we explore the second book of the novel. We will discuss this further when we explore the second book of the novel.

Finally, Dostoevsky's observation in his article Three Tales by Edgar Poe can be justly applied to his own method:

"He almost always takes the most exceptional reality, places his hero in the most exceptional external or psychological situation, and with what power of insight, with what striking truthfulness he describes the state of this person's soul!"

The novel was published in installments in Mikhail Katkov's literary and political journal The Russian Messenger (Русский Вестник) from 1879 to 1880. In the December 1879 issue of The Russian Messenger, at Dostoevsky's request, a letter from the writer to Katkov was published. In this letter, Dostoevsky apologized to readers for the delay in the novel's publication:

"This letter is a matter of my conscience. Let any accusations regarding the unfinished novel, if there are any, fall on me alone and not touch the editorial board of 'The Russian Herald,' which, if any accuser could reproach them in this case, it would only be for their extraordinary delicacy towards me as a writer and their constant patient indulgence towards my weakened health..."

In addition to the writer's illness, the delays were also due to significant changes in the novel's original plan during its creation. Some books grew to nearly twice their intended length, and entirely new chapters and books, not initially planned, were added.

" Well, the novel is finished at last! I worked on it for three years, published it over two—a significant moment for me. I want to release a separate edition by Christmas. There’s enormous demand, both locally and from booksellers across Russia; they’re already sending money. As for bidding you farewell, please allow me not to—after all, I intend to live and write for another 20 years,’ wrote Dostoevsky to Nikolai Lyubimov on November 8, 1880, as he sent the novel’s epilogue to the editorial office of The Russian Messenger.

The Brothers Karamazov was published as a separate two-volume edition in early December 1880, achieving phenomenal success—half of the three-thousand-copy print run sold within days. However, the author did not have another twenty years to write a second novel about Alexei Karamazov, as Dostoevsky passed away soon after.

For The Brothers Karamazov published in The Russian Messenger, Katkov paid Dostoevsky 300 rubles per printer's sheet (a publishing volume measure equivalent to 40,000 characters, including spaces). This was approximately three times less than the fees paid to Tolstoy at the time.

The Brothers Karamazov was approximately 45 printer's sheets in length, earning Dostoevsky a total of 13,500 rubles from Katkov. This was not a particularly large sum for such a novel.

Just for fun, here are some prices for random things you could’ve bought in the 1880s.

12,000 rubles — the Zdravnevo estate in Vitebsk province

3,000 rubles — a sable fur coat

5 rubles — a bottle of curaçao liqueur

2 rubles — a bottle of Jamaican rum

50 rubles — 500 bottles of Russian dark beer

900 rubles — a decorated stove

1,290 rubles — 1 kilogram of gold

2,000 rubles — a comfortable four-seater carriage

60 rubles — a silk umbrella

3 rubles — a copper coffee pot

3 rubles — a pair of Russian felt boots (valenki)

The Brothers Karamazov captivated the public even before its completion, solidifying Dostoevsky's reputation as a spiritual teacher in the eyes of many. For instance, the writer and Dostoevsky's collaborator, Varvara Timofeeva, vividly described the author’s public reading of The Confession of a Passionate Heart as follows:

...It was a mystery play titled: "The Last Judgment, or Life and Death"... It was an anatomical dissection of a body infected with gangrene—an unveiling of the wounds and ailments of our dulled conscience, our unhealthy, rotten, still serf-bound life... Layer by layer, wound by wound... pus, stench... the exhausting heat of agony... death throes... And refreshing, healing smiles... and gentle, pain-relieving words—from a strong, healthy being at the deathbed. It was a conversation between old and new Russia, a conversation between the Karamazov brothers—Dmitri and Alyosha.

According to the memoirist, the audience was initially surprised and whispered comments like, 'Maniac!... Holy fool!... Strange...' However, by the end of the reading, they were deeply moved and rewarded Dostoevsky with thunderous applause. Many readers expressed similar sentiments, as Dostoevsky noted in a letter dated April 23, 1880:

...They won't let me write... [...] The Karamazovs are to blame again. ...So many people come to me daily, so many seek my acquaintance, invite me to their homes—that I am completely lost here and now I'm fleeing Petersburg!

Critics, however, were less favorable toward the novel.

Critics viewed Dostoevsky's post-exile work as overly mystical, noting his embrace of left-wing Slavophilism and pochvennichestvo in opposition to European ideals. They claimed he advocated for the intelligentsia to abandon pride and free will in favor of monastic values.

The religious establishment also expressed concerns. The Holy Synod's Chief Prosecutor Pobedonostsev worried in 1882:

They truly think and preach that Dostoevsky created some new religion of love and emerged as a new prophet in the Russian world and even within the Russian church.

Dostoevsky died of pulmonary tuberculosis on January 28 (February 9, New Style), 1881, just two months after completing the publication of The Brothers Karamazov. His funeral turned into a grand public procession, attended by thousands, with his coffin carried by hand to the grave. The words from the Gospel of John, which Dostoevsky had chosen as the epigraph for The Brothers Karamazov, were engraved on his tombstone.

The Brothers Karamazov was widely regarded as Dostoevsky's spiritual testament and had a profound influence on 20th-century literature. Writers such as Franz Kafka, James Joyce, François Mauriac, Thomas Mann (particularly in Doctor Faustus), F. Scott Fitzgerald, and John Steinbeck were notably impacted by the novel.

It is known that The Brothers Karamazov was the last book Leo Tolstoy read

Ludwig Wittgenstein, Martin Heidegger, and Albert Einstein all spoke about the profound influence of the novel on their lives and perspectives. Albert Camus dedicated many lines to Ivan Karamazov in his essay The Rebel, while Sigmund Freud, who called The Brothers Karamazov 'the greatest novel ever written,' authored the article Dostoevsky and Parricide. In it, Freud analyzed not only the novel’s plot but also Dostoevsky’s biography through the lens of the Oedipus complex.

The Brothers Karamazov has been adapted for the stage and screen numerous times. Early productions were banned by censors, who deemed the novel to contain 'something morally poisonous.' The first successful staging took place in 1899. Since then, particularly in the 20th and 21st centuries, the novel has inspired a wide range of theatrical adaptations, including ballet and rock opera.

Notable screen adaptations include the three-part film by Ivan Pyriev, Mikhail Ulyanov, and Kirill Lavrov, with the latter two completing the project after Pyriev's death. Another notable adaptation is The Boys (1990), which featured cameo appearances by two of Dostoevsky’s descendants—his great-grandson, Dmitry, and great-great-grandson, Alexei.

Mikhail Mikhailovich Bakhtin (1895 – 1975) was a Russian philosopher and literary critic who worked on the philosophy of language, ethics, and literary theory.

Thank you for putting all this effort into this book club. This is the level of information I would expect from a tertiary institution, just delivered in a much easier to understand package.

It is a pity that Friedrich Nietzsche never read TBK. He encountered Dostoevsky by chance in a French translation, which inexplicably combined two stories, The Landlady and Notes From the Underground that never should have been merged together. In the latter book, Dostoevsky dealt with the subject of revenge. In The Genealogy of Morals, Nietzsche took this up in his noteworthy treatment of “ressentment,” admired by Freud. In Twilight of the Idols, Nietzsche famously said that Dostoevsky was “the only psychologist from whom I have anything to. learn.” He was not one to praise other writers lightly.