Epilogue - That might be the subject of a new tale; but our present one is ended.

The final article on "Crime and Punishment"! A six-month journey has come to an end. To everyone who took this journey with me - my deepest gratitude.

Hello, Dostoevsky enthusiast!

If you've just joined us as we prepare to read The Brothers Karamazov, welcome! This is my final article about Crime and Punishment. As we conclude our reading, I should note: if you want to avoid spoilers, you may want to stop here. However, if you'd like to join our discussion of the novel's final chapters, please read on.

Organizational post about The Brothers Karamazov you can find here

List of articles by chapters C&P you can find here

Reading schedule is here.

I congratulate everyone on completing this long journey! We have read and analyzed 41 chapters of the novel!

Many critics who question the Christian foundation of Dostoevsky's work and argue that everything is "more complex" view the novel's epilogue as artificially "tacked on," merely serving Dostoevsky's ideological purposes. Others, however, maintain that the epilogue contains the work's essential meaning, its moral core, and holds paramount importance.

What causes such disputes about the epilogue? Let's examine it in order.

The "author" or narrator, as we've agreed to call him, maintains a subtle presence here too. He employs irony when describing Raskolnikov's trial proceedings, presenting events through the lens of a casual observer who refuses to fully comprehend what is unfolding.

"The particular circumstance that he had never opened the purse and didn't even know how much money was in it seemed incredible. Finally, some even admitted the possibility that he truly hadn't looked in the purse [...] but from this they immediately concluded that the crime itself could not have happened except under temporary insanity, so to speak, under a morbid monomania of murder and robbery, without further aims or calculations for profit. All this was almost crude."

The fashionable theory of temporary insanity—this theory gained prominence in Western Europe during the 1860s. Dr. Krafft-Ebing detailed it in his article "The Study of Temporary or Transitory Insanity (Mania transitoria), Explained for Doctors and Lawyers" in 1866. The theory proposed that men, typically aged 20–30, would temporarily lose their mental faculties for several hours and commit acts they later couldn't explain.

Dostoevsky employs irony here, as Raskolnikov's behavior clearly doesn't align with this theory of temporary insanity. His motives were entirely different. Nevertheless, in court, this theory served as a mitigating circumstance that reduced his sentence from 20 to 8 years.

All dates here are in the old style, as they were during Dostoevsky's time; to convert them to the modern calendar dates, add 11 days.

The trial spanned five months. Though Dostoevsky portrayed this as swift, it was unusually long for such a case—courts could typically deliver verdicts within a day. However, Dostoevsky likely chose this timing deliberately, wanting the sentence to coincide with late December. This echoes his own fate—December 22 (when Dostoevsky was nearly executed at Semyonovsky Square in 1849).

Finally, let's look at the amount that Raskolnikov stole—317 rubles and 60 kopeks. There were also, as we remember, eight items that he examined at the beginning of Part 2 before hiding them under the stone.

"He rushed to the corner, thrust his hand under the wallpaper, and began pulling out items and loading them into his pockets. There were eight pieces in total: two small boxes with earrings or something similar—he didn't look closely; then four small morocco cases. One chain was simply wrapped in newspaper. And something else in newspaper, apparently a medal..."

For context, Raskolnikov's mother received a minimum pension of 120 rubles per year (10 rubles monthly). Since historical prices vary inconsistently, we can use this pension as a reference point instead of bread prices. Comparing it to today's Russian subsistence minimum of 14,375 rubles (about $140), one historical ruble equals roughly $14. Therefore, Raskolnikov stole the equivalent of approximately $4,446—plus several items of modest value.

Hard Labor

Raskolnikov received an eight-year sentence of hard labor in Omsk. The location held special significance—Dostoevsky himself had served five years there, allowing him to paint a vivid picture of prison life.

For readers curious about conditions in this prison camp, Dostoevsky chronicled his experiences in Notes from the Dead House.

The Omsk fortress was uniquely situated in the heart of the city, where modern buildings now stand atop its ruins. It was a compact settlement enclosed by a high fence, with civilian life continuing just beyond its walls. This proximity to the general population explains Sonya's frequent visits. While some question how she gained access to see him, it wasn’t unusual—prisoners regularly encountered free citizens during their work details. Escape was impossible, however, as all inmates wore permanent shackles that were soldered directly to their bodies. These restraints remained in place at all times, even during bathing and sleeping.

The Conclusion of the Story for Other Members of Raskolnikov's Family

Dostoevsky reveals the fates of Raskolnikov's mother and sister. Pulkheria Alexandrovna falls into a long illness and dies of grief, though she assures everyone before her death that Rodya will return in nine months—as if being born anew. Dunya marries Razumikhin.

The death of Rodion's mother carries deep significance. When she first arrived in Petersburg, Dostoevsky described her as a youthful-looking 43-year-old woman. Yet she speaks of seeing Marfa's ghost visiting her. This detail becomes crucial—according to Svidrigailov, who also saw his wife's ghost, such apparitions appear only to those near death. This proved true for both Svidrigailov and Pulkheria. Her death seems almost fated, as if a mother's heart simply could not endure the knowledge that her son was a murderer.

One could say that Raskolnikov killed his mother. She was his third victim.

"My conscience is clear"

In prison, Raskolnikov once again "shut himself off from everyone," showing little interest in news about his family and barely paying attention to Sonya, often being rude to her during her visits. This rudeness, Dostoevsky points out, was mainly because he was tormented by wounded pride and felt ashamed before Sonya that he had not proven to be "extraordinary."

However, the main point lies elsewhere. According to Dostoevsky's remarkable expression, here "in prison, in freedom"—that is, freedom from the "necessities" he had imposed upon himself in the outside world—he repeatedly contemplates his fate and still finds no error in his theory, seeing his crime only in the fact that he couldn't bear the murder and turned himself in. He is tormented by his lack of repentance—yet he also rejects false repentance:

"My conscience is clear. Of course, a criminal act was committed; of course, the letter of the law was broken and blood was spilled, so take my head for the letter of the law... and that's enough! Of course, in that case, even many benefactors of humanity, who didn't inherit power but seized it themselves, should have been executed at their very first steps. But those people endured their steps, and therefore they were right, while I didn't endure it, and thus, I had no right to allow myself this step."

As we can see, both his language and worldview have hardly changed.

A gulf formed between him and the other convicts. The convicts, recognizing his pride and contempt for everyone, came to strongly dislike him and once nearly killed him in church. This occurred while he was observing Lent (that is, preparing for Holy Communion, fasting, and attending church services) along with the other convicts. It's characteristic, however, that such open aggression from the convicts toward him was caused not by his arrogance, but by their recognition of his unbelief, which became especially evident in the church setting. We should note that Raskolnikov was probably observing Lent for the first time in many years since leaving home. However, we never learn whether he actually took communion. Dostoevsky is generally sparse in mentioning church rites and sacraments.

It is possible that his first communion after committing the crime could have been one of the reasons for the change in his behavior and his acceptance that he could transform. The devil in him might have retreated.

Raskolnikov's Third Dream - The Apocalypse

Just before Easter, Raskolnikov falls ill and has disturbing dreams. He dreams that all of humanity is infected with certain bacteria—trichinae—resulting in everyone becoming convinced that they alone know the truth. People begin waging war against each other for the triumph of their own truth. They destroy each other in rage and mindlessness, the earth is drenched in blood: "they gathered in whole armies against one another, but these armies would suddenly begin to tear themselves apart, their ranks would break up, soldiers would attack one another, stabbing and cutting, biting and devouring each other."

Only a few people still remember how to save themselves, but no one knows where they are. Here again appears Raskolnikov's persistent thought about the "chosen ones." This is how reality could unfold if everyone were to think and act like Raskolnikov. But he still doesn’t understand this yet, dismissing what he saw in his dream as "meaningless delirium.”

The imagery in Raskolnikov's dreams is oriented by Dostoevsky toward biblical apocalyptic prophecies. In the so-called "Little Apocalypse," Christ answers the disciples’ question about the signs of the "end of the world:"

"...you will hear of wars and rumors of wars [...] For nation will rise against nation, and kingdom against kingdom, and there will be famines, plagues, and earthquakes in various places; all this is but the beginning of the birth pangs. [...] And then many will fall away, and they will betray one another and hate one another; and many false prophets will arise and lead many astray; and because of the increase of lawlessness, the love of many will grow cold." "For then there will be great suffering, such as has not been from the beginning of the world until now, no, and never will be" (Matt. 24: 6-12, 21).

Dostoevsky would later develop this dream further in his story The Dream of a Ridiculous Man. I highly recommend reading it if you have the time.

Feelings for Sonya

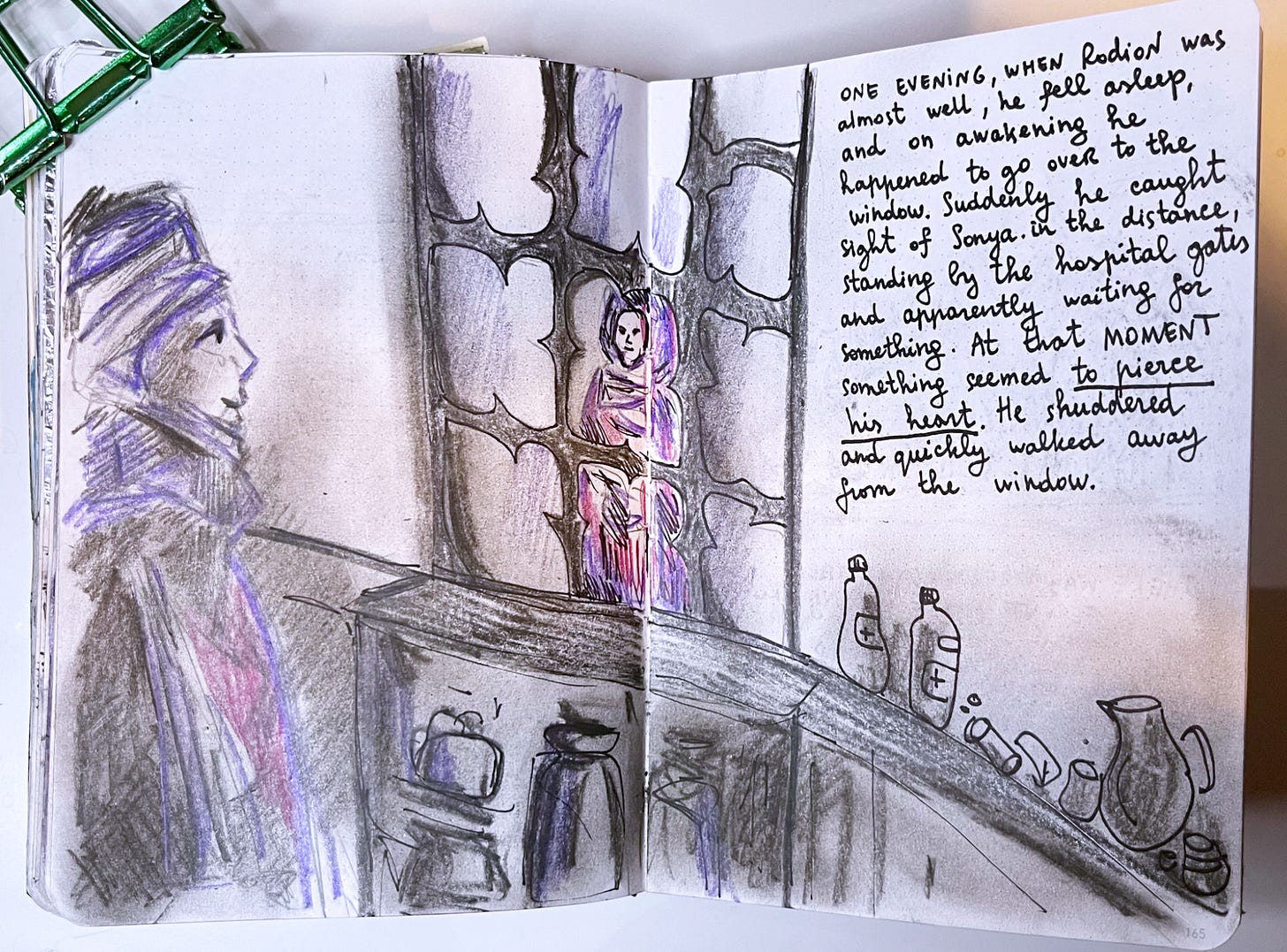

The impression from this "delirium" stays with him for a long time and manifests in a completely unexpected way—a genuine feeling for Sonya awakens in his heart. How could this happen? How could such a radical transformation of Raskolnikov's soul occur, contradicting Razumikhin's prediction: "he will never love"? Of course, the birth of love is always a mystery. We can recall that Raskolnikov's feelings for Sonya began to emerge back in Petersburg. Remember how he rejoices—while preparing to attend Marmeladov's memorial service—that "there, soon, he will see Sonya."

However, this seemingly sudden transformation of Raskolnikov in prison lies at the heart of many people's distrust of the epilogue of Crime and Punishment. After all, Raskolnikov, as we noted above, often exists on the border between reality and dreams. And sleep is a temporary death. Based on this, and on the fact that Raskolnikov had essentially killed himself through his crime—something he admits: "I killed myself, not the old woman"—his transformation takes on a deeper meaning. In his dreams, Raskolnikov saw not only the socio-historical consequences of his fantasies but also the intensely personal ones: the hellish loneliness of a person who sees only their own truth. His entire being revolted against this.

In the draft notes for the novel, there is this entry:

"Or perhaps there is a law of nature that we don't know and which cries out within us. Dream."

This is usually attributed to Raskolnikov's dream about the horse, triggered by his horror before the murder. But in Raskolnikov's prison dreams, there is a far greater horror.

On the Banks of the Irtysh River

Early in the morning, during a break, Rodion approached the riverbank and sat down on some logs piled there. In this scene, the strange wish expressed by both Svidrigailov and Porfiry to Raskolnikov finally came true: "what you need now is just air, air, air!"

Here, air represents, firstly, that very freedom from the obligations Raskolnikov had invented for himself to become "extraordinary," and secondly, the recognition of himself not in a tiny square of empirical reality, where everything, as he believes, depends on his will and decisions, but in a three-dimensional real world governed by entirely different forces.

After mentioning the Old Testament Abraham, the writer speaks of the New Testament, of Lazarus's resurrection, and of the future renewal and rebirth of Raskolnikov himself (and therefore, of the world and humanity, because Raskolnikov always thought of his fate—and here Dostoevsky undoubtedly agrees with him—as a concentrated expression of humanity's fate). Thus, in the epilogue of Crime and Punishment, past, present, and future time are united.

However, as we have seen, there is still no repentance. There is only an indefinite melancholy.

Suddenly, Sonya appeared beside him. She approached almost inaudibly and sat down next to him. They were alone; no one could see them. The guard had turned away at that moment. How it happened, Raskolnikov himself didn’t know, but suddenly something seemed to sweep him up and throw him at her feet. He wept and embraced her knees. At first, she was terribly frightened, and her whole face turned deathly pale. She jumped up and, trembling, looked at him. But immediately, in that same moment, she understood everything. Infinite happiness illuminated her eyes; she understood, and there was no longer any doubt for her that he loved her, loved her infinitely, and that this moment had finally come...

In the epilogue, no "religious transformation" of Raskolnikov occurs yet; it only shows the birth of a feeling of love that would save them both—Rodion and Sonya. This love truly saves not only Raskolnikov but also Sonya, as she too needs rebirth.

The Future

If we consider, according to Dostoevsky's own indications, that the main action of the novel takes place in July 1865, and "almost a year and a half has passed" since Raskolnikov's crime, then the final events of the epilogue occur after Easter 1867 (April 16th that year).

Dostoevsky finished work on the novel by the end of 1866, and in February 1867, issue No. 12 of Russian Messenger was published with the novel's conclusion. This means that for the novel's readers, the events of the second epilogue were still in the immediate future. Raskolnikov and Sonya had not yet sat together and had not yet been saved by the feeling of love in their timeline. For Dostoevsky, this was a hypothetical future.

Thus begins the story of Raskolnikov and Sonya's rebirth, and thus ends another attempt of a proud mind to rebuild the world "justly," according to its own understanding. It ends with hope for Raskolnikov; but no one will absolve him of the guilt for three deaths—Alyona Ivanovna, gentle Lizaveta, and his own mother. The outcome could have been far more terrible if not for Sonya's involvement. Had Raskolnikov completely isolated himself in anger and despair, he would have perished himself and, almost certainly, would have destroyed more than one living being.

In the preparatory materials for the novel, Dostoevsky left this note:

"NB. FINAL LINE: God's ways of finding man are inscrutable."

With this, we conclude our reading of Crime and Punishment. What a journey it has been—from July 2024 to early January 2025. I am deeply grateful to everyone who supported me along this path and helped me see it through: those who left comments, asked thought-provoking questions, shared fascinating theories, brought laughter with their jokes, offered encouragement, and shared kind words about my drawings.

I would like to express special gratitude to you - without you, it would have been difficult for me to reach the epilogue: Cams Campbell, Ellie, Leonard Gaya, Heather Weaver, Chris L., Christina Madarász, Paula Duvall, Paúl Delaustro, diary.ofa.reader, Glenys Murnane, Robert Parson, Hyun Woo Kim, Karen McCreary, Kate.

We have reached the end of this journey together! And soon, another shall begin!

Thank you very much, Dana, for guiding everyone through this novel with such kindness and knowledge. Your ability to lead a reading group is truly outstanding! Keep in touch!

I loved how in the epilogue Dostoevsky turned the bleak story of the novel into a message of redemption and hope through love. The epilogue made the novel for me! Contrast it to Tolstoy’s rather perfunctory first epilogue to my other Russian big read, War and Peace. To use the current colloquialisms, Tolstoy “phoned it in” in his epilogue while Dostoevsky “stuck the landing” in his.