Dostoevsky's séance experiences and an unexpected canine savior

In this piece, I'll explore Dostoevsky's attitude towards séances, his personal experiences with them, and how mysticism influenced his life and work.

Hello, Dostoevsky enthusiast!

For the Halloween season, I've prepared a series of articles that blend the mystical with the frightening. In this piece, I'll explore Dostoevsky's attitude towards séances, his personal experiences with them, and how mysticism influenced his life and work.

Rest assured, this article contains no spoilers for his literary works.

Don't forget to subscribe to the channel—you won't want to miss my next article in this series, "The mystery of Dostoevsky's father's death: Was he murdered?" coming on October 31.

And as we approach Fyodor Mikhailovich's birthday (November 11), we'll delve into a paradoxical topic: the circumstances of his death.

Invitation to the First Séance

On January 8, 1876, Nikolai Wagner wrote to Fyodor Mikhailovich about Madame St. Clair's arrival in St. Petersburg. "She's not a professional medium," Nikolai Petrovich emphasized. "She's a wealthy lady who agreed to come for the local scientific commission. She possesses extraordinary power. Aksakov will be delighted to see you."

Who was this Nikolai Wagner?

A children's writer and professor of zoology, Wagner became acquainted with spiritualism in 1871. He attended spiritualist séances, wrote extensively about them, and debated with critics of occultism—including the renowned scientist Dmitri Mendeleev, after whom the periodic table of chemical elements is named.

On April 1, 1875, Wagner published an article in the "European Herald" about the existence of spirits who allegedly communicated with séance participants about the other world. He viewed ghosts not as fantasies or hallucinations but as complete or partial embodiments of the immaterial. Wagner claimed that spirits would sing, dance, smoke pipes, and leave various objects in the room at the request of séance participants.

Wagner maintained close communication with the spiritualist Helena Blavatsky, who lived in America and allegedly managed to embody the spirit of a deceased Georgian named Mikhalko. She also claimed that deceased writers could transmit the texts of their unfinished works to mediums—and sent Wagner the final part of Dickens' novel "The Mystery of Edwin Drood". According to Blavatsky, Dickens' spirit appeared several times to a barely literate newspaper delivery boy and dictated the text of the unfinished novel. This case sparked considerable controversy, with spiritualism supporters tending to believe its authenticity, as the text allegedly contained not a single mistake despite the boy's limited literacy.

As fate would have it, Dostoevsky's entire family fell ill during those days. The writer could only accept the invitation a month later, attending a séance on February 13. Two other famous writers—Nikolai Leskov and Pyotr Boborykin—were also present.

What Fyodor Mikhailovich experienced in Aksakov's (he is also the writer) apartment left him profoundly affected: the séance "made quite a strong impression on me". Though he didn't record the events in detail, Nikolai Leskov provided a comprehensive account of what transpired at house No. 6 on Nevsky Prospect.

Communication with Spirits #1. Tapping on the Table

"We gathered at Mr. Aksakov's house around 8 o'clock in the evening. There were five of us outsiders, the host and hostess, and the medium herself... The outsiders were: Professors Wagner and Butlerov, and the writers Dostoevsky, Boborykin, and myself. First, we sat at an ordinary round table with one leg and placed our hands on it... Spiritualistic knocks—not dry ones made by the table leg on the floor, but soft ones that seemed to come from within the wood of the table itself—were heard immediately. They responded very quickly by tapping out the English alphabet, which Aksakov recited. In most cases, they made it unnecessary to spell out the entire word and anticipated the answer with an affirmative knock of three taps."

As far as I understand, the first experiment consisted of Aksakov reciting the alphabet, and the "spirit" knocking on the table leg when the correct letter was named. It was like an audio version of a Ouija board, where they move a special pointer across a board with the alphabet.

Saint-Clair understood that she might be suspected of tapping with her feet under the table. She suggested making any sounds on the tabletop, and the "spirits" were supposed to repeat them. The writers began scratching the table with an iron key, tracing "arbitrary figures and flourishes." The unpleasant scraping sound was repeated "with complete accuracy, but extremely quietly" a couple of moments later. The medium's hands remained motionless. There were no sound recording devices in those years.

It's difficult to say for certain how that trick was performed.

Communication with Spirits #2. Mind Reading

Leskov continues to describe the experience of attending that séance.

"Throughout the séance, the room was illuminated by a ceiling lamp with a small frosted shade. It provided even light, clear enough for us to write numbers and names on the table.

The first experiment was conducted by F. M. Dostoevsky: he wrote seven names (in French) and noted one of these names on a separate piece of paper, which he held in his hand. Then he ran his pencil down the list of names he had compiled, and when he reached the name Theodore, three affirmative sounds were heard. Dostoevsky said that this was indeed the name he had thought of. Then Boborykin wrote and received false answers. After them, they asked me to write. I wrote the name of one of my deceased acquaintances - Michel - on a separate piece of paper, and, clutching this piece of paper in my hand, began to write names on a sheet; but at the first two names I wrote, negative responses were heard, and as soon as I had written the letters Mich... it quickly and firmly tapped three affirmative times.

Both I and F. M. Dostoevsky wrote the names we had thought of so secretly that no one could see it. F.M. did this by standing up from the table and moving aside, while I wrote with my hands under the table."

Who could have really been reading minds then - spirits or a magician? I'm certain that Saint-Clair had a professional assistant. Modern magicians have repeatedly demonstrated that they can "guess" a person's thoughts. There are a huge number of shows. Dostoevsky actually quite predictably chose his own name: Theodore is the variation of Fyodor, in fact.

Communication with Spirits #3. Flying Furniture

"Then we proceeded to the experiment of lifting the table," recalled Leskov. "It rose into the air, seemingly about 6-8 vershoks (25-35 cm), and after holding this position for about 7-8 seconds, quickly descended. A few minutes later, the phenomenon repeated, with the table staying airborne longer this time."

Experienced spiritualists were aware that a round table could be easily lifted with a foot or knee. To prevent such deception, they used a square table with outward-sloping legs and a thick tabletop—impossible for one person to lift without detection. Nevertheless, in the medium's presence, the table rose twice, once remaining suspended "for quite a long time".

For the next experiment, they placed two differently sounding bells under a third table. The bells rang, first one, then both together. Leskov, seated next to the medium, dismissed the possibility that Saint-Clair had secretly removed her narrow boots to manipulate the bells with her toes. The accordion experiment, where Butlerov pushed the instrument under the table while holding one end, also succeeded, despite the impossibility of playing the hanging keys with feet. Fyodor Mikhailovich then took up the musical instrument.

"In Dostoevsky's hands, the accordion remained silent, but simultaneously, something tugged strongly at the edge of Aksakov's dress. The medium, through Aksakov, then suggested replacing the accordion with a handkerchief. Fyodor Mikhailovich produced his handkerchief and, lowering it under the table, held it by the tip. After a few minutes, he reported that the handkerchief was pulling to the side. However, a small misunderstanding then occurred, which brought the séance to an end."

Boborykin later revealed that this "small misunderstanding" was an incautious remark by Fyodor Mikhailovich. The writer voiced doubts that these tuggings couldn't be explained by the ordinary dexterity of the evening's organizer herself. This accusation infuriated Saint-Clair, who, flushing with anger, cursed the celebrity in English, promptly terminating the séance.

What was Dostoevsky's opinion about this séance

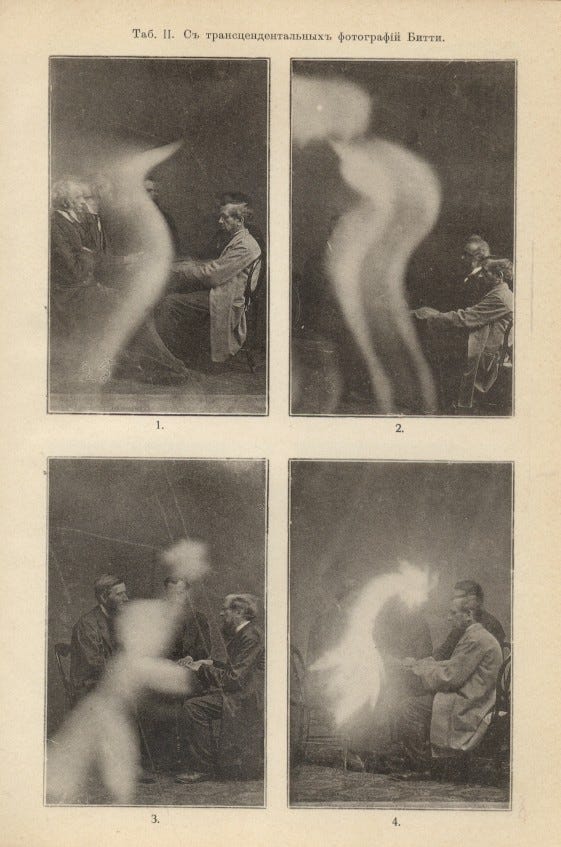

A month before attending the séance, Dostoevsky had already addressed the topic of spiritualism in his "Writer's Diary". In his January 1876 article "Spiritualism. Something About Devils. The Extraordinary Cunning of Devils, If They Are Indeed Devils" («Спиритизм. Нечто о чертях. Чрезвычайная хитрость чертей, если только это черти»), he portrayed spiritualism as a phenomenon superficially amusing yet profoundly emblematic of the times—and perilous in its implications for Christians. He saw it as crass materialism, a poor substitute for genuine faith, and a dangerous dalliance with forces inimical to humanity.

True to his paradoxical style, Dostoevsky pursued the "spiritualist hypothesis" to its logical end: cunning devils (for spirits, in his view, were nothing but devils) aim to lead humanity to moral ruin. He regarded spiritualism as an alien import, threatening not only to divide Russian intellectual society but also—should it spread—to incite sectarian unrest among the masses.

Did his stance shift after experiencing Saint-Clair's séance?

"After that remarkable séance, I suddenly realized—or rather, suddenly knew—that not only do I disbelieve in spiritualism, but, moreover, I have no desire to believe at all. No evidence will ever shake this conviction. This is what I gleaned from the séance and later clarified for myself. I confess, this realization was almost comforting, as I had felt some trepidation before the séance. I'll add that this isn't merely personal; I sense something universal in my observation. I perceive here a special law of human nature, common to all and pertaining precisely to faith and disbelief in general. It became clear to me then, through this very experience, this very séance—what strength disbelief can muster and develop within itself, at a given moment, entirely beyond your will, yet in accordance with your secret desire... Probably the same holds true for faith."

Yet, despite Dostoevsky's proclamation of this "universal law of disbelief", discovered through his spiritualist experiment, his imagination and mystical sensibilities continued to teeter between acknowledging and dismissing the "phenomena" he witnessed. In his terminology, this meant vacillating on the existence of spirits hostile to humanity (while he wholly rejected the spiritualists' "mystical doctrine").

Notably, in a letter to the censor of "A Writer's Diary", he likened the spiritualist encounter to the poetics of Pushkin's "The Queen of Spades". The very next day, he began work on the chapter "The Devil. Ivan Fyodorovich's Nightmare" in "The Brothers Karamazov", which itself mimics a séance. In this chapter, as Dostoevsky puts it, the fantastic brushes so close to reality that the reader nearly believes it. In essence, Dostoevsky's personal experience led him to conclude that the true séance—a modern mystery or "devil's vaudeville"—unfolds within our own minds.

The Mystical in Dostoevsky's Life

Dostoevsky's spiritual rebirth began at Semyonovsky Square in 1849. Condemned with other members of the Petrashevsky Circle, he faced execution. Though the sentence was commuted to four years of hard labor, those moments at the post became a turning point. Truly preparing for death, he later wrote to his brother that he was "literally dead for three-quarters of an hour" and saw "cherubim in the sky—small birds with human facial features." He marveled, "I was certain that it was all over—time to die, and now I live once again!"

In the "utter hell" of Omsk prison, among society's outcasts, Dostoevsky's revolutionary ideas dissolved. Unexpectedly, he found what he had sought but missed among the revolutionaries—Christ. This discovery came in a harsh environment where life could be lost for a mere kopeck.

A mystical incident, recounted by fellow convict Szymon Tokarzewski, occurred during Dostoevsky's hospital stay for pneumonia. Despite his serious condition, Dostoevsky remembered the hospital as a peaceful respite from hard labor. However, this tranquility was disrupted by a near-fatal event. When a doctor carelessly left Dostoevsky an envelope containing a few rubles—a fortune by prison standards—an envious patient plotted to poison him. As Dostoevsky reached for the tainted milk, a dog named Suango intervened.

The dog, whom Dostoevsky had befriended earlier, jumped onto the bed, licked him, and knocked over the poisoned milk before lapping it up. The dog perished, but Dostoevsky survived. Witnessing this, the other prisoners crossed themselves, seeing it as divine providence and a sign of Dostoevsky's favor with Christ.

Fascination with Mystics

Contemporary Dostoevsky scholars are examining the Orthodox writer's apparent interest in mystics and spiritualism. Evidence includes a book by the Swedish mystic Emanuel Swedenborg in his library and his documented reading of an article by N. Stakhov titled "Inhabitants of Planets" (Жители планет).

Dostoevsky studied occultists, but likely as source material for his books rather than out of personal belief. His "polyphonic" writing style allows characters—even those opposing Christ—to speak convincingly, as if Dostoevsky himself held their views. He believed a writer's ability to transform was crucial to creating truthful literature.

Swedenborg's concept of a "voluntary hell"—where sinners choose eternal damnation due to their hatred of Christ—found its way into Dostoevsky's works. Swedenborg describes a vision of a demon lifted towards God, suffering more intensely the closer it gets to Christ, until the angels mercifully release it.

The haunting vision of eternity as a "smoky little room with spiders," seen by Arkady Svidrigailov in "Crime and Punishment," (this topic is described in chapter 4.1 of the novel, you can read more about it here) echoes Swedenborg's vivid descriptions of the afterlife's materiality. Dostoevsky even penned a satirical story, "Bobok," inspired by these ideas.

I invite you to read "Bobok" with me, which will be in December. See this post for more details.

In this story, the deceased visit one another and engage in depraved activities, which Dostoevsky terms "the debauchery of final hopes." Swedenborg's notion that one's earthly life determines their afterlife status as angel or demon may have influenced other works by Dostoevsky.

A Second Séance?

There are reports on the internet that Dostoevsky participated in a second séance, at the home of close acquaintances, where a female medium, a certain Madame B., was also present.

To be honest, I haven't found reliable confirmation of this. There is supposedly his confession to the linguist Jan Baudouin de Courtenay that after this second séance, Dostoevsky intended to engage in spiritualism in the most serious manner. There were apparently also "tricks" with a handkerchief under the table, flying tables, and guessing of chosen numbers.

Nevertheless, Dostoevsky did not take up spiritualism, so we can consider the information to be false. Although he died couple of years after.

In his perception of spiritualism, Dostoevsky is caught between the Scylla of souls being seduced by devils and the Charybdis of disbelief. For Dostoevsky, in matters of faith, moral conviction in truth was extremely important, not proof of faith through miracles.

The real séance, in Dostoevsky's opinion, takes place within each person's soul, with its doubts, contradictions, and dark secrets. As Bakhtin (the great schollar of Dostoevsky’s poetics) showed, the world itself was not the subject of Dostoevsky's depiction, but rather the reflection of this world in the consciousness of his characters. Similarly, spiritualist phenomena themselves, their truth or falsity, did not interest Dostoevsky; he was interested in the influence of these phenomena on human consciousness and the soul. The séance, where these phenomena manifest, testing the human soul, becomes similar to Dostoevsky's creative method of creating certain situations that are meant to test the souls of his characters. Thus, the medium here is the writer himself, materializing through his writing the "unknown forces" hidden in the soul: "the séance becomes a metaphor for the creative process".

After Dostoevsky's Death

On February 22, 1881, N. P. Wagner—who had invited Dostoevsky to his first séance and had become a family friend—paid a courtesy visit to Mrs. Dostoevskaya. During their conversation, the writer's widow, responding to Wagner's critical remark about her "sickly appearance," noted that she was not only deeply shaken by her husband's death (who had died on January 28 according to the old style calendar) but also felt helpless in practical matters. During the writer's lifetime, she had always consulted with him on her actions; now she had to make decisions on her own. Wagner hinted that such consultation with F. M. Dostoevsky remained possible—one only needed to attend a spiritualist séance.

The story continued. In a letter dated February 23, 1881, Wagner approached Dostoevskaya with a request to allow him to summon the spirit of the deceased writer and invited her to meet with his spiritualist acquaintances. Dostoevskaya accepted his latter proposal; however, the other spiritualists made an extremely negative impression on her. Apparently, she felt they were too insistent on drawing her into spiritualist activities. During the meeting, she made N. P. Wagner promise: under no circumstances to attempt to summon the spirit of the deceased writer.

That same evening, as Dostoevskaya indicates in her memoirs, she and her daughter had the same nightmarish dream. They both saw F. M. Dostoevsky "deathly pale, with a suffering face, rising from somewhere, as if from the grave." Taking into account this coincidence of dreams, Dostoevskaya assumed that Wagner had broken his promise. Characteristically, she interpreted the writer's "suffering face" as a prohibition addressed specifically to her:

"...the first thought that came to my mind was: N. P., in the company of two spiritualists who had been with him, held a séance and began to summon Fyodor Mikhailovich's soul. And it was at this moment that Fyodor Mikhailovich appeared in a dream before both of us and, with his suffering appearance, forever forbade me to disturb his eternal peace."

In her letter to Wagner dated February 25, 1881, Dostoevskaya asked him to honestly tell her if he had been involved in summoning the spirit of the deceased writer. Wagner assured her in response that he would under no circumstances engage in such a thing without her permission. Moreover, considering that in her letter, unlike in her memoirs, she did not mention her daughter's dream, he suggested that her dream was caused by ordinary emotional distress.

From the spiritualists' point of view, F. M. Dostoevsky, after his transition to another world, became common property, to which all who wished should have access. However, it is also believed that spiritualists cannot force a spirit to come if it does not want to. In general, whether or not Wagner summoned Dostoevsky's spirit remains authentically unknown.

Do you believe in ghosts, spirits, and séances? Share your thoughts.

Wow! This is fascinating material. I’m embarrassed to admit that I might have been a bit creeped out in parts. It’s interesting to see how long seances have been practiced and how, even then, they knew tricks were (sometimes?) employed. Still going strong today!

I’m going to have to try to find a copy of Dostoevsky’s journals in English. They would be such an interesting read. He is a fascinating man.

Thank you for this very interesting article.