5.1-5.2 “And might I a-a-ask you just what you meant, madam”

Are you ready for the last third of the novel? The first two chapters are warm-ups, describing the overall challenging atmosphere, and then each new chapter will be captivating, I promise.

Hello, Dostoevsky enthusiast!

List of articles by chapters you can find here

Reading schedule is here.

Part Five opens with a shift away from Raskolnikov's narrative. He fades into the background, barely present as a character. In the first chapter, Luzhin merely inquires about his attendance at the funeral feast. The second chapter finds Raskolnikov as a silent observer, sitting at the memorial dinner table, watching the quarrel unfold between Katerina Ivanovna and Amalia (whose patronymic curiously changes).

Are you ready for the last third of the novel? The first two chapters are warm-ups, describing the overall challenging atmosphere, and then each new chapter will be captivating, I promise.

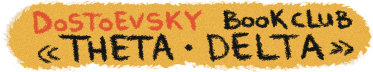

Lebeziatnikov — the "progressive"

The fifth part of the novel opens with a conversation between Luzhin and his friend, the "progressive" Andrei Lebeziatnikov. Pyotr Petrovich is staying in Lebeziatnikov's apartment, located in the same building as the Marmeladovs.

Through the "vulgar and simple-minded" Lebeziatnikov, Dostoevsky satirizes the prevailing ideas among many "advanced" thinkers of the time. These ideas called for a radical revision of all human relationships—between children and parents, men and women, husbands and wives—as well as the organization of communes. They even asserted that "social activity" was "much higher, for example, than any Raphael or Pushkin, because it's more useful!"

This critique also takes aim at Turgenev's novel "Fathers and Sons" (originally titled "Fathers and Children" («Отцы и дети»), not just sons).

Dostoevsky's disdain for the society he encountered after nearly a decade of isolation in prison, jail, and the army is palpable. Returning to the capital in the late 1850s after leaving in the late 1840s, he witnessed a dramatic shift: thinkers had grown more bitter, and youth more harsh. These were the seeds of ideas that, despite Dostoevsky's opposition, would later capture the masses and lead to the catastrophes of the 20th century—its revolutions and wars. Yet this transformation occurred gradually, with society, like a frog in slowly heating water, unaware of its impending fate.

Lebeziatnikov's ideas reflect those fashionable at the time, many drawn from Chernyshevsky's works—the youth's idol—particularly his novel "What Is to Be Done?" and the article "The Anthropological Principle in Philosophy" (1860). Dostoevsky also engages in a literary debate with Turgenev's "Fathers and Sons."

Advocating for the rejection of all "vile prejudices," including funeral feasts, Lebeziatnikov refuses to attend Marmeladov's memorial dinner. He quips, "However, it might be possible to go, just to laugh. But it's a pity there won't be any priests. Otherwise, I would definitely go." He even laments his parents' death, but only because "if they were still alive, how I would have struck them with protest!" This echoes Turgenev's Bazarov, the nihilist protagonist who expresses similar sentiments about his parents.

About Luzhin's Money

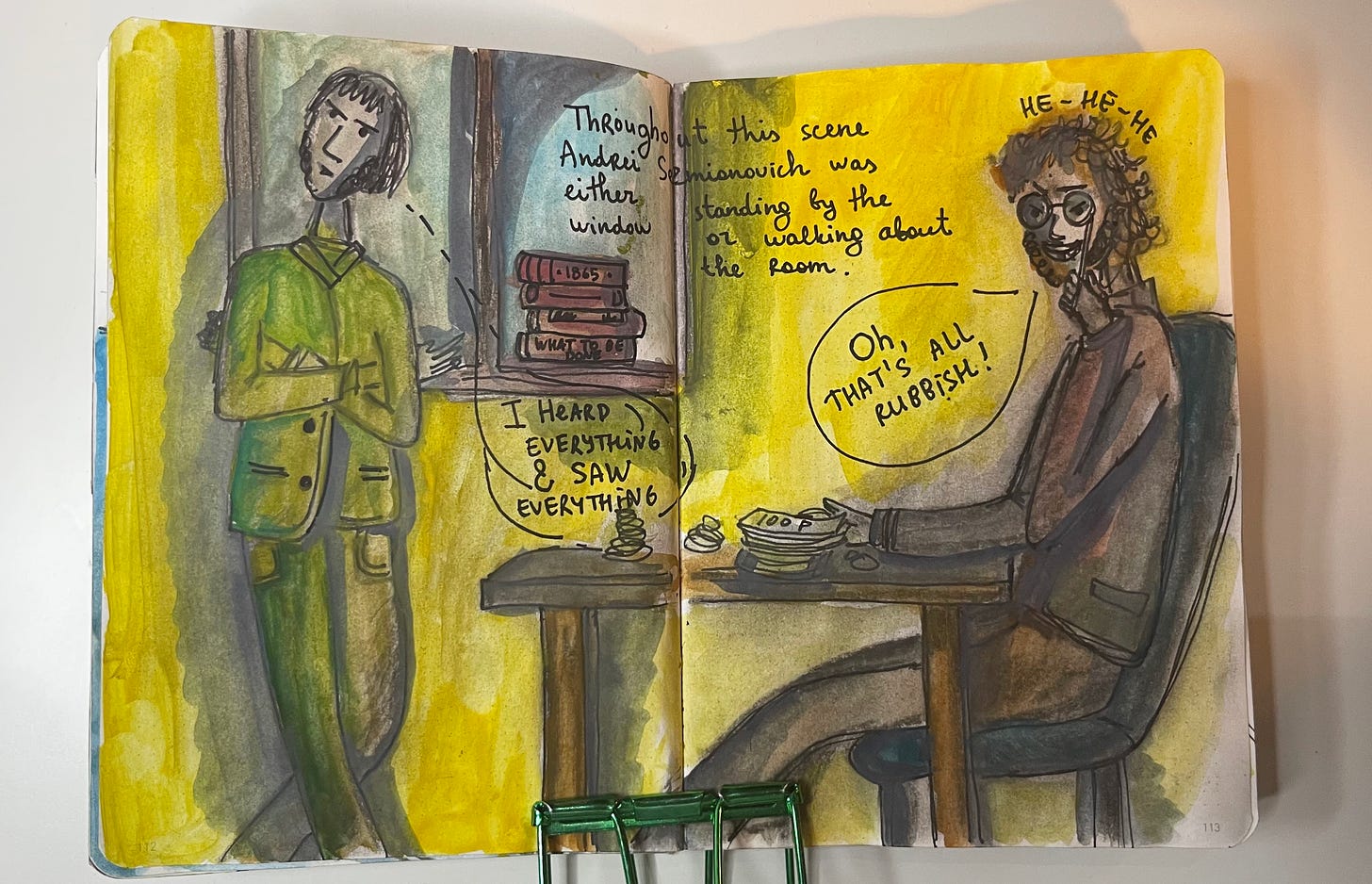

Luzhin sits and counts bundles of banknotes and series. Series are state treasury bills worth 50 silver rubles, issued in batches. They yield interest—2 rubles 16 kopecks per year—functioning like a short-term deposit in a current account and valid for 8 years.

In the first chapter, I touched on money in the Russian Empire when the old woman gave Raskolnikov "2 yellow tickets" (2 rubles). Paper tickets resembled today's banknotes but operated differently. Their exchange value in silver could fluctuate based on circumstances. These credit bills varied in color according to their value:

1 ruble — yellow

3 rubles — green

5 rubles — blue

10 rubles — red

25 rubles — purple

50 rubles — gray

100 rubles — light yellow until 1866, then rainbow-colored with Catherine II's image. Dostoevsky takes a slight liberty here; in his 1865 novel’s year, Raskolnikov's 100 rubles are already rainbow-colored. We'll forgive this minor anachronism.

Due to this color coding, people often referred to money by color rather than denomination.

Luzhin gave Sonya a red bill of 10 rubles, while on the table, he had bundles of rainbow banknotes—the highest denomination.

Could Katerina Ivanovna receive assistance as a widow?

Luzhin mentions the possibility of temporary assistance for the widow of a civil servant who died while in service.

According to the laws of the Russian Empire, civil servants were entitled to a full pension after 35 years of impeccable service. For 30 years of service, two-thirds of the full pension was awarded, and for 20 years - one-third. In the event of a civil servant's death, the widow could receive half of the allotted amount, as well as one-sixth for each child. However, the question arises: did Marmeladov have a sufficiently long and impeccable service?

There was also a provision according to which the family of a civil servant who had not served long enough for a pension could receive a benefit equal to one year's salary. But considering Marmeladov's behavior, his family would most likely not receive anything.

There was a similar case in Dostoevsky's family. In 1856, the writer tried to obtain a benefit for his future first wife Isaeva after the death of her first husband. Despite having many patrons, the outcome of the petition was unfavorable. The benefit, equal to her husband's annual salary of 285 rubles, was paid only 5 years after his death, and even then only after numerous reminders and requests.

Thus, Katerina Ivanovna Marmeladova would probably not receive any assistance.

A funeral feast "beyond one's means"

Katerina Ivanovna spent all her money on a "luxurious funeral feast" while her children lacked proper clothing and shoes. Her motivation was to "show off," though it's worth noting that she's gravely ill, both physically and mentally. She's disappointed that the respectable guests she had hoped for didn't attend the funeral feast.

Funeral feasts have a unique characteristic: they bring together people from various social strata, differing significantly in class, status, and position. Only aristocrats might be absent. Despite the vast financial disparity between Luzhin and Marmeladova, their coexistence doesn't seem out of place. This is a hallmark of Dostoevsky's prose—readers don't question why such diverse characters interact. Unlike Tolstoy, who emphasizes class distinctions, Dostoevsky creates a sense of equality that feels natural and harmonious.

Irritated and indignant, Katerina Ivanovna addresses only Raskolnikov, whispering her pent-up feelings and righteous indignation about the failed funeral feast. She then begins making public, ironic, and offensive remarks about the guests. Katerina Ivanovna particularly targets the landlady Amalia, sitting next to her, nodding openly at her while speaking to Raskolnikov:

"Look at her: she's goggling her eyes, she senses we're talking about her but can't understand, and her eyes are popping out. Pah, what an owl! Ha-ha-ha!"

Katerina Ivanovna boasts about a commendation certificate stating her father was a colonel, while simultaneously lamenting her terrible life, insisting she should have been rich and successful. She recalls a Frenchman named "Mangot," who taught her French at the institute.

This character has a real-life counterpart from the Moscow boarding school of Chermak, where Dostoevsky studied in 1834-36. Mangot was a 45-year-old supervisor and tutor during Dostoevsky's time there.

The scandal intensifies. Neither Amalia Ivanovna nor the guests are as oblivious as Katerina Ivanovna assumes. Despite it being her husband's funeral feast, and the guests trying to be patient with her grief, tensions rise.

"The red spots on her cheeks glowed stronger, her chest heaving. She was on the brink of causing a scene."

Amalia Ivanovna endures until they both start boasting about whose father was better. The situation escalates when Amalia threatens to evict Katerina for non-payment and disrespectAnd it completely spirals out of control when Sonya's "yellow ticket" is mentioned, meaning that she works as a prostitute. At least in this, Katerina Ivanovna is consistent — she doesn't let anyone insult Sonya, recognizing the sacrifice she made for her and her children. As the conflict nears a physical altercation, Luzhin appears...

By the way, what do you think, did Lebeziatnikov really beat Katerina Ivanovna, as Marmeladov told Raskolnikov in the second chapter? Or did she attack him herself if he started saying something about Sonia? What do you think now, after everything you know about the characters?

PS Literary reference

At the end of chapter 5.1, Lebeziatnikov says:

“And if—to assume an absurd idea—I were ever to enter into a legal marriage, I should actually be glad to wear your wretched horns: I’d say to my wife: “My friend, up till now I have merely loved you, but now I respect you, because you have actually made a protest!” You’re laughing? That’s because you’re incapable of shaking yourself free from your preconceived ideas!”

The source for the motif "My friend, until now I have only loved you, now I respect you" is Druzhinin's 1847 novella "Polinka Saks." In this work, the protagonist Konstantin Saks, upon discovering his wife's love for another man, selflessly grants her freedom and facilitates her union with her beloved. This is a relatively obscure novella now, remaining mostly known to literary scholars, but English translations exist; I've seen at least Katz's translation.

But this book greatly impressed Dostoevsky at the time, as he references it not only here in "Crime and Punishment," but also in "Demons." In the drafts for them, there are numerous remarks such as "like Saks' role," "to play Saks," "want to play Saks here," "to act out from Polinka Saks." In general, the character of Konstantin Saks was unusual for that time, which is why it stuck in Dostoevsky's memory. It wasn't so much that he liked it, but rather that he wanted to engage in a polemic again. The venom of sarcasm, embedded by Dostoevsky in the formulation that respect is higher than love in relationships, speaks to his perception of these innovations in marriage among the "new people" — modern progressives. He didn't understand them. For Dostoevsky, love is above all else.

Was digressing in a novel to criticize current thoughts a thing with these Russian authors? Last week was a slog through War and Peace reading Tolstoy’s attempt to dismantle the Great Man Theory in History.

Katarina is another unstable character. Judging by her past, she probably was the instigator in the tussle with Leb. She has reasons to lie, he does not. And Luzhin is getting more dislikable as the book progresses. Counting his money but he would not part with any to bring Dunya and Pulcheria to St. Petersburg. Reminds me of Scrooge.

I second others’ comments about how helpful your summary is. And i so enjoy your art work. It’s such a rich experience to have you & this group for my first reading of Crime & Punishment.