4.3 You understand now?…

One could say that this chapter is an interlude. That is, a brief respite between the conclusion of one arc and the beginning of another.

Hello, Dostoevsky enthusiast!

List of articles by chapters you can find here

Reading schedule is here.

We have just resolved the issue of Dunya and Luzhin's marriage, a question that has been lingering since the very beginning of the novel. And at the end of the chapter, Rodion "finally" (or not?) breaks ties with his family. But in his style - without really saying anything, only causing pain.

A bit about Luzhin and the history of Dostoevsky's family

Dostoevsky’s older sister Varvara married Piotr Karepin, who was 26 years her senior! She was only 17-18 at the time. She married more out of necessity, as both Dostoevsky parents had died. Varvara’s husband also became the guardian (more financial than in terms of upbringing) of Fyodor Mikhailovich and his other siblings. There were five children in total. But that’s not all—all of the Karepins’ children were somewhat sickly. The Dostoevsky family wasn’t known for good health, especially the men.

Varvara’s son Alexander, who became the inspiration and prototype for Luzhin, suffered from a mild psychological disorder. It didn’t particularly interfere with his studies or work as a military doctor. However, his relatives’ testimonies about him are quite strange. Fyodor Mikhailovich’s daughter even called him an idiot.

In the summer of 1866, while writing the novel, Dostoevsky spent time in Lublin with his sister’s family and this nephew, getting to know him well. Everyone mocked Alexander’s behavior and his desire to find an «ideal» young bride of 16-17 years old, «far from all modern ideas about women’s equality and work.» He simply despised emancipated women. At that time, he was 27 years old. Dostoevsky wrote about him:

«For years, he had been dreaming lustfully of marriage, all while saving money and waiting. He thought with rapture, in deepest secrecy, of a virtuous and poor girl (necessarily poor), very young, very pretty, noble and educated, very timid, who had experienced great misfortune and would submit completely to him. She would consider him her savior for life, worship him, obey him, and admire him alone. How many scenes, how many voluptuous episodes he had created in his imagination on this seductive and playful theme, while resting quietly from his affairs!»

As always, every character or event can be traced back to some reflection from Dostoevsky's life.

Literary allusion

“Piotr Petrovich, having fought his way up from nowhere, had become morbidly fond of admiring himself, and had a high opinion of his own intelligence and abilities; sometimes, when alone, he even used to gaze in admiration at his face in the mirror. ”

This is another trait that brings Luzhin's character closer to Gogol's Chichikov from the novel "Dead Souls". In Gogol's work, Chichikov "being left alone, began to examine himself at leisure in the mirror, like an artist - with aesthetic feeling and con amore. It turned out that everything was somehow even better than before <...> it was simply a picture. Artist, take up your brush and paint!"

For those unfamiliar with "Dead Souls," Chichikov is a cunning landowner and swindler. His scheme involves purchasing "dead souls"—records of deceased peasants from the last census—to mortgage them as if alive and sell to the state. Driven by greed, Chichikov will stop at nothing for financial gain. He embodies the petty, vulgar evil that lurks in society, masquerading as a respectable gentleman "in a dress suit."

But this Chichikov himself also has a dead soul. Just like Luzhin.\

Publishing in the mid-19th century

The second half of the 19th century marked the dawn of typography in Russia. One could say that before this, the printing industry was practically non-existent for many reasons, but primarily due to censorship. With the death of Nicholas I, amid strengthening liberal sentiments, the "era of censorship terror" came to an end. The most reactionary censors were removed from their positions. In 1865, a new law was enacted—according to it, metropolitan periodicals and books exceeding ten printed sheets for Russian works and twenty printed sheets for translated editions were exempted from preliminary censorship.

This was a huge relief for magazines and books. Post-publication censorship is always more liberal than that which doesn't allow printing at all. Nevertheless, there were still many punishments—publishers of "harmful" content were penalized with fines, confiscation and seizure of books, and were brought to trial.

In the 1860s, everything was developing—many fields of science, so specialized educational literature also began to appear. This is precisely why Dunya and Razumikhin chose for their future company this very promising business. If they were to open a publishing house, they could become rich, but they could also go bankrupt.

However, it's important to remember that this business was very costly and complex. The book printing process itself consisted of a huge number of steps.

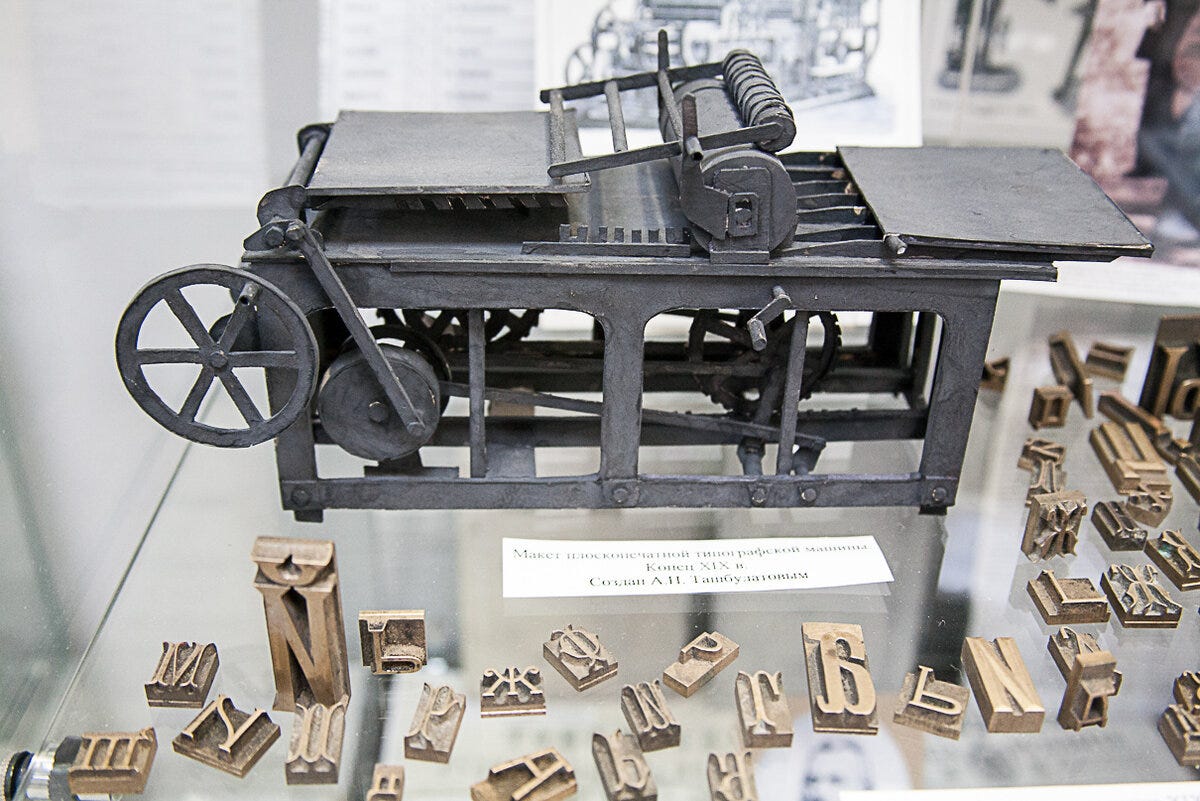

If Dunya and Razumikhin took on the role of publishers-printers, they would incur costs for equipment, paper, as well as for typesetting the text itself. Most likely, they wouldn't be able to afford huge printing machines, but would do everything on a small hand-operated press, which looked something like this.

Typesetting was the most complex part of this chain. It had to be manually composed from individual letters — stamps into words and sentences, formatted to fit the page size. Mechanized typesetting only appeared by the end of the century. If a correction was needed, the text was completely disassembled and reassembled. This was a very lengthy and resource-intensive process

However, under favorable circumstances, this brought great profit: for example, a separate edition of the novel "Demons," undertaken by Dostoevsky himself in 1873 (thanks to his wife Anna), brought the writer almost 4,000 rubles in income, while the publisher A. F. Bazunov offered only 500 "and even with payment in installments over two years."

By the way, publishers very often offered Dostoevsky an "unfavorable price," as they knew that he was "in need" and often could not wait for more advantageous offers.

"Everyone was happy, and within five minutes they were even laughing."

The three thousand rubles bequeathed to Dunya by Marfa Petrovna drastically changed the situation. There was now reason to hope and dream of a better future. Razumikhin was especially joyful, pleased with Luzhin's disappearance. "Only Raskolnikov remained sitting in the same place, almost gloomy and even distracted. He, who had insisted most strongly on Luzhin's departure, now seemed the least interested in what had happened."

He suddenly felt his alienation from all living things once again. An abyss separated him from his once beloved mother and sister. He stood up, "slowly turned towards the door and slowly walked out of the room."

More about Gogol — and why I remembered him

Nikolai Gogol is one of those writers in whose work the mystical merges with reality. He is a visionary artist who believed that the world is inhabited by devils, creatures that man himself generates through his sins, vices, and misdeeds. His death is also shrouded in mystery. He feared being buried alive. And legends circulated that this indeed happened — when he was reburied, his body was found turned over, as if it had moved in the coffin. But that's not what we're discussing now. Before his death, he wrote to his friends about these sinister beings, saying he was afraid to encounter them.

It's terrifying!.. The soul freezes with horror at the mere premonition of the afterlife's grandeur and those higher spiritual creations of God, before which all the magnificence of His creations that we see and marvel at here is but dust. My entire dying constitution groans, sensing the colossal growths and fruits, whose seeds we sowed in life, not foreseeing and not hearing what monstrosities would rise from them...".

Weren't these the very monstrosities that Goya, another visionary artist like Gogol, tried to depict?

The seed is Raskolnikov's crime, the fruit is the otherworldly monster that grew from this seed. When Raskolnikov killed, he "did not suspect or hear" anything, but now he understood. As does Razumikhin.

The corridor was dark; they were standing by a lamp. For a minute they stared at one another in silence. Razumikhin remembered that minute all his life. Raskolnikov’s intense, burning gaze seemed to grow more intense moment by moment, penetrating into his very soul and consciousness. Suddenly Razumikhin shuddered. Something strange seemed to have passed from one to the other… Some idea, some hint had flashed between them, something terrible, monstrous, suddenly understood on both sides… Razumikhin grew pale as a corpse.

‘You understand now?…’ Raskolnikov suddenly asked

Immediately after these words of Raskolnikov, something extraordinarily significant occurred, as if visually summarizing everything that Dostoevsky had said before about "human nature" - the possessor of two consciousnesses - the external rational and the internal spiritual.

Raskolnikov asks Razumikhin twice if he understands him. The first time before this stunning scene and the second - immediately after it. But the word "understand" has two completely different meanings here: in the first case, quite concrete, mundane, in the second - deeply mystical, relating essentially not to understanding, but to comprehension.

What was comprehended "from both sides?"

This is not about Raskolnikov's crime itself, but about what it metaphysically gave birth to. A strange "something", like some kind of snake-idea, slipped between Raskolnikov and Razumikhin. This is the creature Gogol spoke of. Standing face to face with Razumikhin, Rodion suddenly "understood" - he sensed with his spiritual consciousness the presence of some terrible, hideous "creature" next to him.

Raskolnikov's gaze, intensifying with each moment, penetrated into Razumikhin's soul, into his consciousness. Then Razumikhin "understood" too and turned pale as death. He remembered this minute for the rest of his life. But, as it turns out later, even after this minute, he did not understand rationally that Raskolnikov was a murderer.

Immersing oneself in Dostoevsky's work, one must forget about psychology or psychoanalysis. With them, one can approach character, the mental makeup, but not the spiritual makeup of a person. Dostoevsky, in many scenes and in analysis, resorts precisely to the spiritual, to what cannot be described by textbooks, but works at the level of intuitions.

Spiritual consciousness rarely coincides in us with rational consciousness. That is why Dostoevsky says that much can be known unconsciously. But it is precisely this knowledge, unconscious in relation to reason, that leads a person to comprehend genuine realities.

What are your thoughts on this chapter?

Rodion is the only one in the room not feeling relief because of the deathly darkness that has taken over him—no wonder he must entirely retreat from his family and friend. What a horrible existence. How does one break out of such a prison?

I was intently reading your comments of 4.3 while sitting at a coffee waiting for a friend. At the end, I looked up and she was sitting at the table with me! She said, “ I have been here for five minutes.” I told her I was absorbed in Dostoevsky and apologized. We both laughed. This is a great compliment to your essays!