4.1-4.2 Incidentally, do you believe in ghosts?

First, we'll explore Svidrigailov's beliefs, particularly his encounters with ghosts. Then, we'll join the characters at the table—to discover whether Dunya will indeed marry Luzhin.

Hello, Dostoevsky enthusiast!

List of articles by chapters you can find here

Reading schedule is here.

We begin the second half of the book. Part 4 opens with a chapter featuring Svidrigailov. Let's revisit who Arkady Ivanovich Svidrigailov is. In the plot, he's about 45 years old.

He first appears in Raskolnikov's mother's letter (chapter 1.3). She recounts how he made advances towards Dunya, unfairly tarnishing her reputation. However, the situation resolved itself—Svidrigailov's wife, Marfa, realized her mistake and went about apologizing, assuring everyone of Dunya's respectability.

Subsequently, Dunya and Marfa formed an unlikely friendship. Marfa apologized profusely, even gifting Dunya an expensive watch—the same one Razumikhin jealously examined, mistakenly believing it was from Luzhin.

Then came Marfa's sudden death. She bequeathed 3000 rubles to Dunya—an enormous sum, considering Dunya's mother was earning merely 120 rubles a year. Arkady himself then decided to leave for Petersburg, following Dunya!

He took up residence near Sonya Marmeladova and even followed her home. He's the unsettling man with a cane from chapter 3.4.

Now, true to character, he's crept into Rodion's room while he sleeps and is watching him. It's hard to say which is more unnerving: being followed or being watched in your sleep.

At this point, Svidrigailov speaks for himself for the first time, becoming an active character in the novel.

The Surname Svidrigailov

As we recall, Dostoevsky often gives his main characters "speaking" surnames that convey meaning and reveal character traits. This holds true for Svidrigailov, though the decoding of his name remains somewhat enigmatic. I'll share the most widely accepted interpretation among literary scholars.

A Lithuanian prince named Švitrigaila lived in the 14th-15th centuries. This historical figure played a role in Russian history, making him familiar to Dostoevsky. Contemporary accounts described Švitrigaila thus:

"Polish writers depict Švitrigaila as a man devoted to wine and idleness, fickle, hot-tempered, reckless, swaying with every wind, and find in him only one redeeming quality—generosity."

Notably, Švitrigaila is a pagan name given at birth; his Christian baptismal name was Boleslav. However, in historical records, the pagan name overshadowed and supplanted the Christian one. Similarly, in Dostoevsky's character, we see the triumph of the pre-Christian, pagan element in man.

Dostoevsky incorporated a pagan element into Svidrigailov's character. Literary scholars believe that Dostoevsky found inspiration for this character in the pagan figure of Quintianus from Sebastiano del Piombo's painting "The Martyrdom of Saint Agatha." Dostoevsky encountered this striking artwork in 1862 at the Pitti Gallery during his visit to Florence. Such a powerful image would have left an indelible impression on the author.

I'd like to make an observation about the novel "The Leopard," which you can now begin reading in the group with

. In that work, too, pagan and Christian elements clash from the very first paragraph. Interestingly, Saint Agatha is a Christian martyr of Sicily—the setting for "The Leopard" and also an inspiration for our villain Svidrigailov. These literary connections never cease to amaze me—everything is interconnected. The timelines are also remarkably close: "The Leopard" begins in 1860, while Raskolnikov's story unfolds in 1865.We'll delve deeper into the significance of this pagan element when we reach Part 6.

What about Marfa's death?

Svidrigailov's account of his wife's death is far from reassuring. While there's no concrete evidence against him—hence his freedom—his past is deeply troubling.

Eight years ago, Marfa inexplicably paid 30,000 rubles to free him from debtors' prison. The novel never reveals why she chose to rescue this unpromising, middle-aged man. Were they previously acquainted? What motivated her to invest such a sum? Their relationship hardly seemed blissful—perhaps he had somehow bewitched her.

Six years ago, Svidrigailov beat his serf Filka (Филька) to death. Eerily, Filka's ghost reportedly appeared to him later! It's possible that Svidrigailov, angered by Marfa's defense of Dunya's reputation, murdered his wife. Had Dunya's name remained tarnished, his chances of seducing her might have improved—not immediately, but eventually out of desperation. The novel suggests that even worse fates can befall people in dire straits. Though Dunya, resourceful as she is, likely would have found an alternative path.

Svidrigailov claims Marfa died of apoplexy—a brain hemorrhage or stroke. Interestingly, the ambiguity surrounding Marfa Petrovna's death—whether natural or violent—mirrors the mystery of Dostoevsky's own father's demise. Mikhail Andreevich Dostoevsky was also said to have died from an apoplectic stroke, yet suspicions of foul play persist to this day. This parallel makes it challenging to determine whether Svidrigailov actually beat his wife to death. While I suspect he did, Dostoevsky likely left this question deliberately unresolved, allowing readers to draw their own conclusions.

If you're curious about the enigmatic circumstances of Dostoevsky's father's death, I'd be happy to delve into some known details around Halloween—it's quite the spine-chilling tale for the season.

Marfa's Ghost Haunts Svidrigailov Thrice

We've already heard about Marfa's ghost from Raskolnikov's mother. Now it appears to Svidrigailov as well. When multiple characters perceive the same phenomenon, it becomes an integral part of the novel's world. Ghosts, in some form or another, exist in Dostoevsky's universe. The question is: how do they manifest? Are they dreams, fantasies, memories, or reality?

Intriguingly, Svidrigailov suggests that ghosts are seen by the sick or dying. If this is true, what does it imply about Raskolnikov's mother? What are your thoughts on this?

“Well, she’s been three times. The first time I saw her was on the actual day of the funeral, an hour after we’d left the cemetery. That was the day before I left to come here. The second time was the day before yesterday, on the way here, at daybreak, at Malaya Vishera station; and the third time was two hours ago, in the flat where I’m staying, in my room. I was alone then.”

Should we believe in the reality of ghosts and their ability to communicate with us? During this era, séances were gaining popularity, sparking both belief and skepticism about the supernatural. Dostoevsky himself attended séances in the 1870s and even wrote an essay on the subject. Much later, after penning the novel, he reflected:

"In subsequent years, I became more familiar with these phenomena. I've concluded that these beings or semi-beings, whatever they may be, are mostly such rubbish that no self-respecting person or Christian should maintain any friendship or acquaintance with them."

The grotesque portrayal of Marfa Petrovna's ghost, appearing to Svidrigailov amid mundane details and chattering about trivialities, echoes Hoffmann's novella "From the Life of Three Friends" (1818). In it, "the deceased aunt haunts the house as a ghost both day and night. <...> During her lifetime, she suffered from stomach problems; there was a cabinet with a medicine chest in the wall, and she would come to count out stomach drops for herself."

Hoffmann explores the metaphysical triumph of the ordinary—an artistic breakthrough where prose pushes its boundaries before venturing into fantasy. Similarly, Svidrigailov's deceased wife appears to him in an eerily ordinary manner. But did Arkady truly see his wife, or was it merely a vivid memory?

Notably, he doesn't link the ghosts' presence to notions of heaven, hell, or the afterlife—another manifestation of his pagan roots. Instead, he posits that eternity follows life, envisioning it as a bathhouse with spiders—a potent image. Does this remind you of anything?

It strongly reminded me of the anime film "Spirited Away". There are also bathhouses with spiders there.

Raskolnikov's room, comparable in size to a small bathhouse, must be stifling and sweltering. Are there spiders lurking in its corners? Or is Rodion himself the spider? Indeed, he will later remark: "I scuttled back into my corner, like a spider." These allusions further emphasize his alienation from the world around him.

Dunya Resolves the Ultimatum

In chapter 4.2, we witness Dunya's formidable character. She articulates her thoughts with such clarity and reason that one might argue she's more deserving of the surname Razumikhin (which, as you'll recall, stems from the word "reason").

Remember, Dunya faced ultimatums from two men who despise each other: Luzhin and Rodion. Luzhin, adhering to patriarchal norms, insists that a future husband should take precedence over family ties. This view was common in a society where, post-marriage, a woman often joined her husband's household, potentially severing ties with her own family. Raskolnikov, too, issued his own ultimatum—choosing Luzhin would mean losing him as a brother.

Dunya, however, spoke eloquently, attempting to broker peace in this impasse. Yet neither man was willing to offer or accept apologies, leaving the situation unresolved.

“You wrote to say that he had insulted you; I think this has to be sorted out at once, and the two of you must make your peace. And if Rodia really did insult you, then he must and shall apologize to you.”

Luzhin reveals his true nature, confirming Raskolnikov's initial assessment based on his mother's letter. There's no mystery here—everything is exactly as Rodion surmised.

Marfa's bequest of 3000 rubles to Dunya completely upends Luzhin's schemes, providing her with a foundation for the future. Luzhin had sought a wife who was destitute and entirely dependent on him, yet still intelligent, beautiful, and well-mannered. Dunya fit this rare profile almost perfectly. However, Luzhin failed to realize that well-mannered, intelligent individuals—even if poor—have no need for the likes of him.

At last, we witness what we've been hoping for, just as Razumikhin did—Dunya decisively ends her engagement with Luzhin. It's a welcome positive development in the story.

The Disturbing Tale of a Young Girl

Luzhin recounts a chilling story:

“There used to live here, and I believe still does, a certain woman called Resslich, a foreigner and furthermore a small moneylender, who also has other business interests. And with this woman, Mr Svidrigailov has long been in some sort of extremely close and mysterious relationship. She used to have a distant female relative living with her, a niece as I believe, a deaf and dumb girl of some fifteen or even only fourteen years of age, for whom this Resslich nursed a violent hatred, grudging her every morsel she ate and even subjecting her to inhuman beatings. One day the girl was found hanged in the attic. The verdict was suicide. After the usual procedures, the case was closed, but later on a report was received that the child had been… cruelly ill-treated by Svidrigailov. ”

It's worth noting that Svidrigailov is currently renting a room in Resslich's apartment. They are well acquainted, and he has frequented her place in Petersburg numerous times. This story likely occurred before his marriage to Marfa. A slightly different version of events will emerge later. Throughout the novel, there are multiple hints suggesting Svidrigailov's involvement in heinous crimes.

The tale of the girl who took her own life was based on a real incident, published in Dostoevsky's journal "Vremya" (Time / Время) in 1861. Notably, the 13-year-old girl was also named Marfa. She hanged herself with her own belt in the attic. This event clearly left a profound impact on Dostoevsky, as he revisited this taboo subject in his later work, "Demons".

Intriguingly, Dostoevsky used the surname Resslich to represent a real-life moneylender named Reisler (Рейслер), whom he despised. In his notes, he wrote that she tormented him and hindered his work.

Defending Sonya's Honor

Luzhin once again disparages Sonya's way of life, prompting Rodion to come to her defense.

"You are not worth the little finger of this unfortunate girl at whom you throw stones."

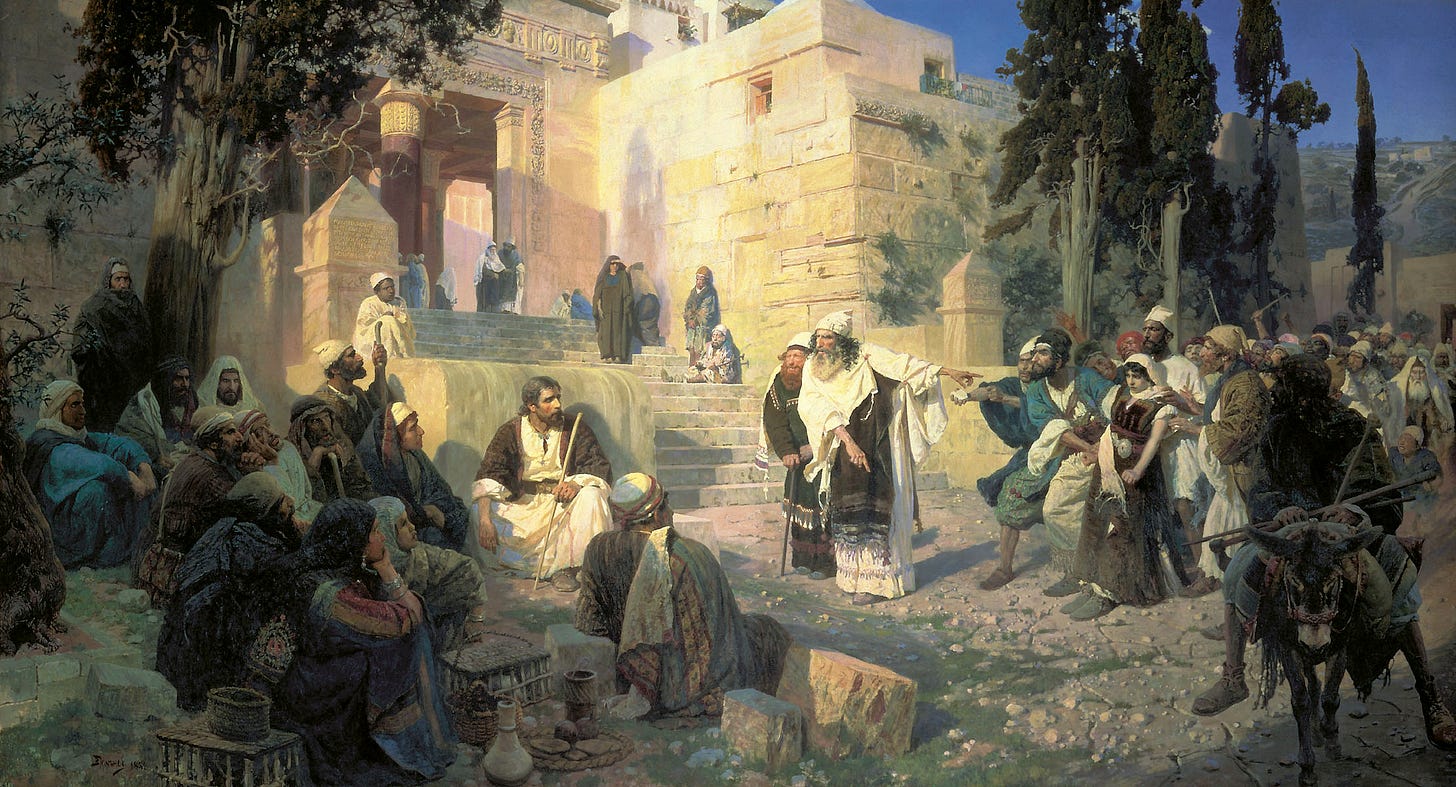

This scene evokes the Gospel episode of "Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery." In that story, scribes and Pharisees bring to Jesus a woman accused of adultery, saying: "Moses commanded us to stone such women. What do you say?" Jesus responds, "Let any one of you who is without sin be the first to throw a stone at her." Faced with this challenge, the accusers, exposed and ashamed, disperse (John 8:3-9).

The Gospel's forgiveness of the adulteress in the temple is central to Dostoevsky's philosophy. In this novel, Sonya's role is crucial for understanding Rodion's journey.

In these first two chapters, we've been introduced to Svidrigailov and bid farewell to Luzhin—though perhaps not for good. Both these unsavory characters seek Dunya's attention and a meeting with her.

What lies ahead?

Will Razumikhin fulfill his promise to Rodion and protect Dunya?

What are your thoughts on this chapter? Did any moments stand out to you, either positively or negatively?

There's something about Svidrigailov that is almost alluring. He's even more despicable than Luzhin, but while Luzhin is so pompous and ridiculous you can just laugh at him, Svidrigailov has this chilling, perfectly calm way to explain himself that makes you almost want to believe him, especially because a lot of his bad deeds are just rumors. I can see why Rodion would be intrigued and even tempted by him, here's someone who's allegedly committed heinous crimes but seems perfectly sure of himself and at peace with his conscience. He's not, of course, or he wouldn't be seeing ghosts. I'm interpreting ghosts in this novel as both hellish creatures wanting to drag sinners down with them, and someone's own conscience tormenting them.

(Side note: this is the time period when ghosts became transparent or translucent in people's imagination, with the invention of photography it was an easy trick to pull, a simple matter of double exposure. So-called "ghost photos" were circulating everywhere.)

I have two theories about Svidrigailov: he's planning to marry Sonia (he's clearly a stalker), and/or possibly he's planning suicide? He talked a lot about a "voyage". Worth nothing that I find his idea of afterlife, a little bathhouse with spiders, strangely cozy and reassuring. I like spiders.

Thank you for promoting The Leopard, Dana! I hadn't realize both novels were set in the same years, indeed it was a time when religion was put under scrutiny. Freemasonry was another symptom of it, with all its pagan symbolism. Do we know what Dostoevsky thought of Freemasons, has he left something on the subject?

After he muders two women (he can be as chilling as Svidrigailov) Razkolnikov holds Razumikhin back from attacking Luzhin and then quietly and distinctively says to him, “Kindly leave the room.” Wish this Raskolnikov showed up more often. Definitely a split up person.