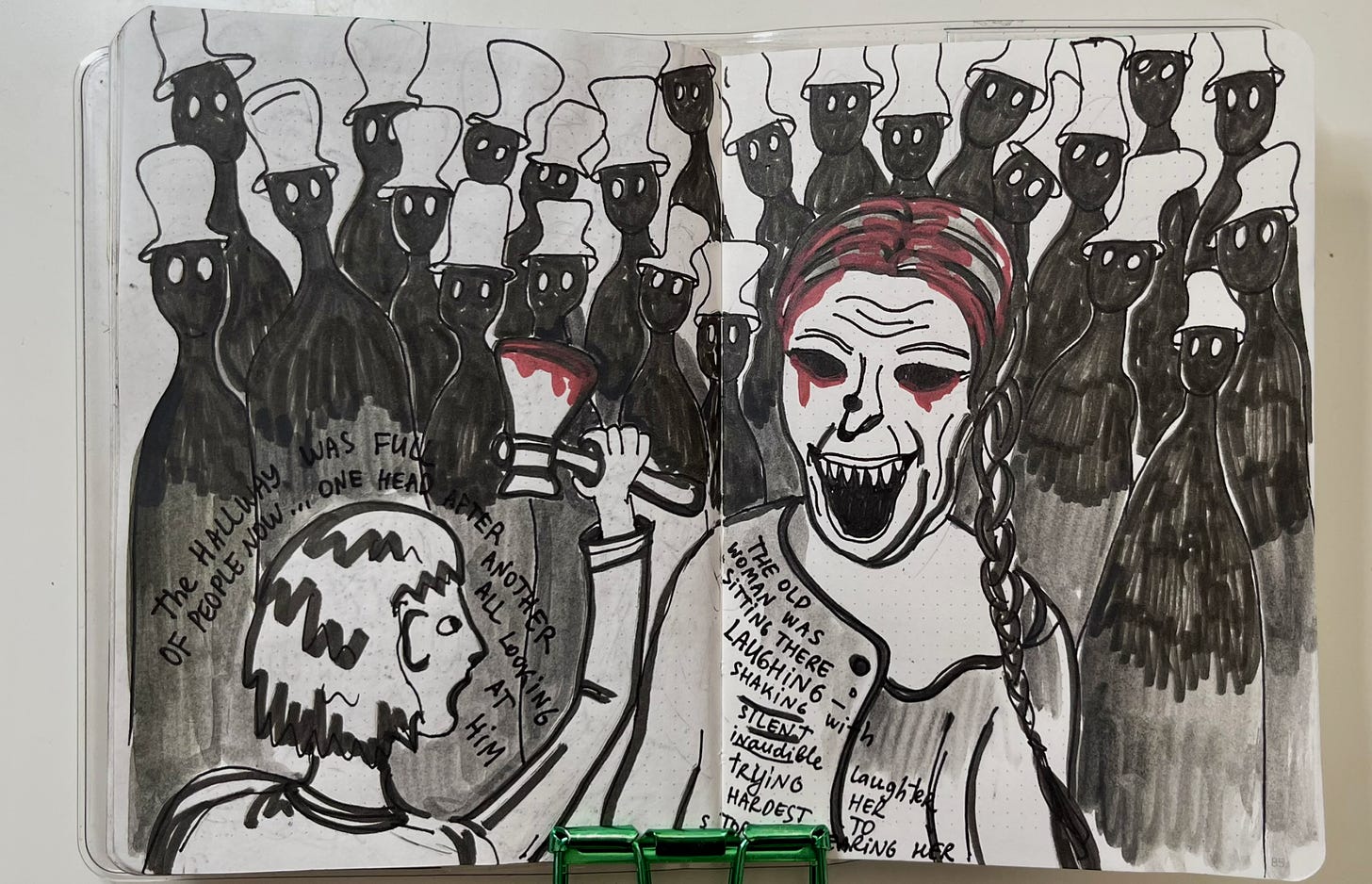

3.6 …everywhere was full of people, one head after another, all looking at him—but all pressed back, silently waiting…

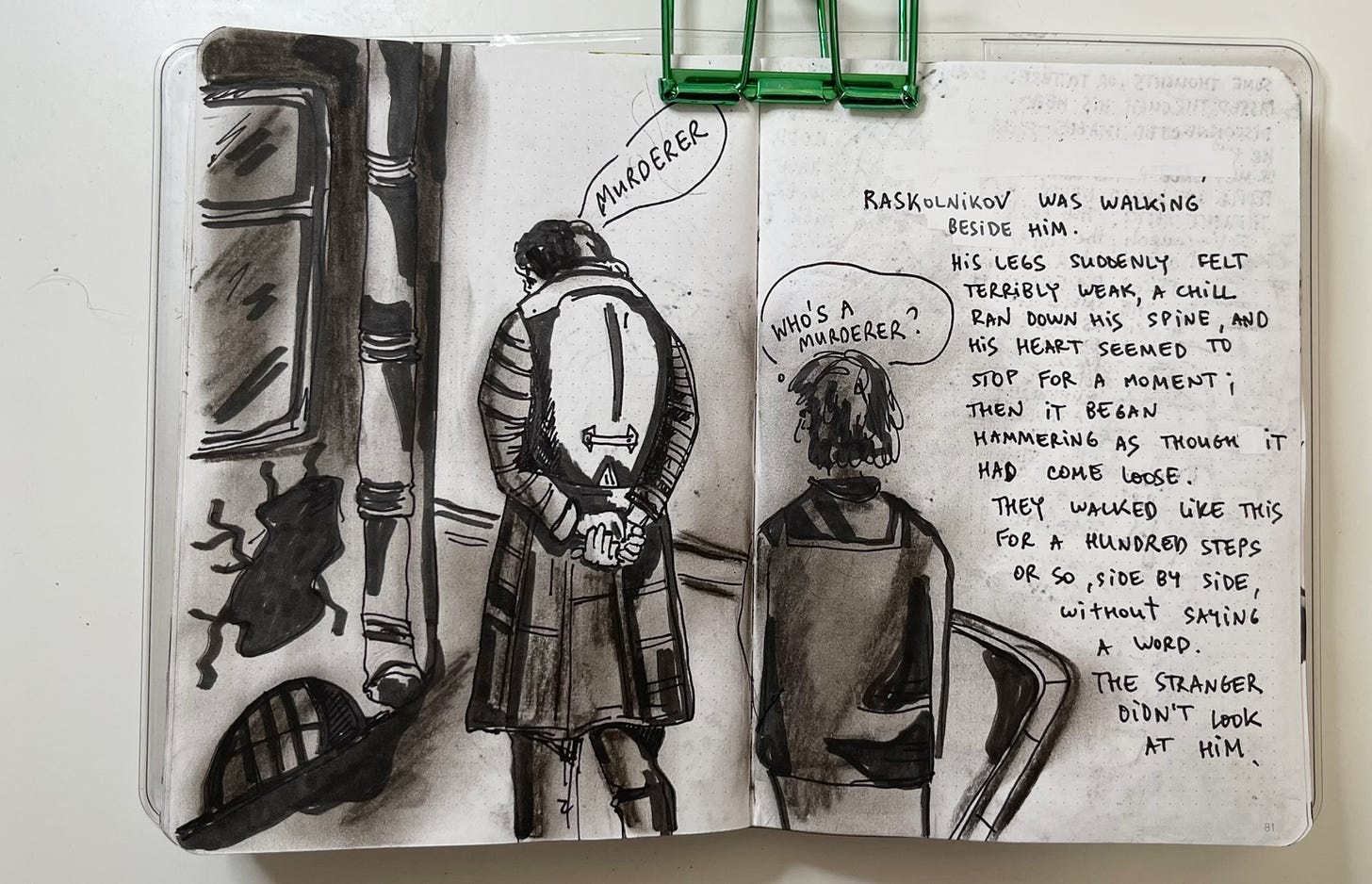

The stranger tells Rodion that he is a murderer. Why? Who is this person? Frightened, Raskolnikov goes home and there he has a terrible dream.

Hello, Dostoevsky enthusiast!

List of articles by chapters you can find here

Reading schedule is here.

How are you? I hope everything is well!

This week has turned into a literal natural disaster. If you haven't heard, Central Europe is experiencing severe floods right now. I live in Wrocław, a city bracing for the arrival of floodwaters that have already swept through many cities to the south.

There's a Netflix series called "High Water" that depicts a flood of similar magnitude in 1997, set right here in Wrocław.

We're expecting citywide shutdowns—from electricity to sewage—for a couple of days. Consequently, there won't be an article on Thursday. Instead, a double chapter covering 4.1-4.2 will be released on Monday.

By the way, congratulations to us all—we've read half the novel!

I can assure you that the second half is more straightforward in terms of pacing—there will be many events, and the reading should feel easier.

The third part of the novel concludes with another cliffhanger. Dostoevsky is a master at ending sections with tense moments—he could write scripts for TV series, given his skill at hooking readers.

Let's recap:

At the end of the first part, Rodion has just killed Alyona Ivanovna—an excellent finale.

The second part closes with Raskolnikov's mother and sister arriving. He faints, mistaking them for the police.

Now, the third part concludes with Raskolnikov's terrifying dream and an unexpected visitor.

The Strange Tradesman

Just as Raskolnikov was walking away from his conversation with Porfiry, confident in his strategy to confuse him, a terrible blow awaits—he is visited by a tradesman who had witnessed his strange behavior during his second nighttime visit to the old pawnbroker's house. A quote from Chapter 2.6 illustrates this encounter:

"What's there to look at?"

"Why not take him to the police station?" — the tradesman suddenly interjected and fell silent.

Raskolnikov glanced over his shoulder, scrutinized him, and said just as quietly and lazily: "Come along!"

"Yes, take him!" — the emboldened tradesman chimed in. "Why did he come asking about that? What's he got on his mind, eh?"

This was the same tradesman from before, who had already harbored suspicions. The tradesman confronts Rodion triumphantly:

"You are a murderer"

This accusation shatters Raskolnikov's newfound confidence, obliterating the sense of "victory" he had felt after his encounter with Porfiry.

Raskolnikov is tormented by thoughts of what this man might have seen and known, and from where. He doesn't recall that the tradesman was in the crowd at the old woman's house. This incident forces Raskolnikov to once again question whether he truly belongs among the "extraordinary" ones.

The tradesman's motives for confronting Raskolnikov remain unclear. However, this isn't the last we'll see of him; he will reappear later in the novel.

New Thoughts on Napoleon

Raskolnikov's thoughts circle back to Napoleon. He wonders: Would Napoleon have stooped to crawling under the old woman's bed for money? Would he have quailed before a drunken commoner?

No, such men are not made that way; a true sovereign, to whom everything is permitted, bombards Toulon, carries out a massacre in Paris, forgets an army in Egypt, wastes half a million men in the Moscow campaign, and gets off with a jest at Vilna. And when he dies, idols are set up to him—which means everything is permitted. No, such men, it seems, are not of flesh but of bronze!

Raskolnikov, berating himself for falling short of the "extraordinary," fixates on Napoleon while disregarding the other luminaries he previously mentioned (Newton, Kepler, Solon). His inadvertent use of "sovereign" unveils his true aspirations. Through his internal monologue, the theory of "benevolent ideas" justifying bloodshed morphs, exposing Raskolnikov's genuine motives.

He grapples with the contradictions in his actions: The old woman was merely a symptom, he muses. He killed a principle but failed to transcend. In the end, he merely committed murder.

His thoughts vacillate between truth and self-delusion. He clings to the belief that humanity is divided into those with the right to kill and those without. Likening himself to socialists, he declares, "I too want to live, or else it's better not to live at all." Paradoxically, for him, living equates to killing. He rationalizes his actions, claiming he couldn't bear to pass a hungry mother with money in his pocket while awaiting "universal happiness."

The mere proximity of his mother and sister sometimes ignites fits of hatred in Raskolnikov (it's a truism that love is easier from afar, "in absentia"). Yet he recognizes his error in "troubling divine Providence, invoking it as witness that I acted not for my own benefit or desires, but with a grand and noble purpose in mind, ha-ha!"—though he interprets this realization merely as proof of his status as an "aesthetic louse." These ruminations lead him not to enlightenment, but to a deepening hatred:

"Oh, how I hate the old woman now! I think I'd kill her again if she came back to life!"

Well, another opportunity will soon present itself to him...

The World of Dreams and Bells

After his encounter with the tradesman, Rodion lies down on the couch and drifts into a half-sleep. His mind conjures images from the past, present, and possible future.

The billiard table and the officer harken back to the overheard conversation where Rodion firmly decides on Alyona Ivanovna as his victim (Chapter 1.6).

The Voznesensky bell tower and its ringing bells feature prominently. This church and bell tower lie at the heart of Rodion's route from his home to the old woman's. Though now demolished, it was once a grand structure where many services were held. Notably, in Chapter 2.1, while en route to the police station, Rodion turns towards this church, momentarily confusing it with the old woman's house—the scene of his crime.

Of the four types of bell ringing, Rodion hears the trezvon («трезвон»)—a festive, joyful peal of all bells with brief pauses, typically reserved for Sundays and holidays.

This ringing carries deep symbolic weight—it hints at the possibility of Rodion's resurrection.

In Russian, the words for Sunday («Воскресенье») and to resurrect («Воскресение») are nearly identical, differing by just one letter. Indeed, the seventh day of the week literally translates to "resurrection day."

As Rodion hears the "Sunday ringing of bells," the specific day matters less than its symbolic resonance with "Resurrection bells"—evoking the resurrection of Lazarus.

Dostoevsky likely drew inspiration from the religious processions common during this period. This scene may also allude to Goethe's Faust:

"On Christ's Resurrection day, after mingling with the people (...) the pealing bells saved Faust from self-poisoning, rekindling his pious devotion as his chest swelled with prayer."

In his reverie, Rodion also envisions a black servants' staircase, awash with slops and eggshells—a potent symbol of the arduous path to redemption. The question lingers: will Rodion find the strength to ascend it?

Raskolnikov's Third Dream

Let's recap Rodion's previously described dreams:

The first dream depicted the beating of a horse (Chapter 1.5).

The second dream involved Rodion hearing a policeman on the stairs beating his landlady and his would-be mother-in-law (Chapter 2.2).

Dostoevsky masterfully crafts Rodion's transition into his third dream, making it nearly imperceptible. We, like Raskolnikov himself, don't immediately realize we're wandering through a dreamscape of Petersburg. However, one might notice the city's unnatural darkness and the moon's clear visibility—impossible during the white nights of summer. Following the tradesman, Raskolnikov finds himself at the old woman's apartment. In the corner, a figure resembling the revived old woman sits on a chair—her head bowed, her face obscured. Raskolnikov, finding the axe right there in the fateful loop, strikes the old woman's crown without hesitation—once, then again. Yet the blows cause her no harm. As he bends down to see her face, he discovers the old woman shaking with laughter. Eerily, someone in the adjacent bedroom also laughs. Enraged, Raskolnikov continues his assault, but the laughter in the bedroom only grows louder, and the old woman's mirth intensifies.

Who is laughing? Could it be that "mute and deaf" spirit that drove Raskolnikov to murder, turning him into a mere instrument of evil intentions, now mocking his impotence? M.M. Bakhtin, the renowned Russian literary critic, offers a different interpretation. He suggests that the laughter in Raskolnikov's dream represents "the dethroning public mockery in the square of the carnival king-impostor."

In Dostoevsky's works, laughter without an explicit source often signifies the presence of evil forces. Raskolnikov himself suspects that the devil has mocked him. These malevolent spirits lack independent power or the ability to fulfill their desires—they can only act through individuals who open their souls, agree with them, and become their instruments.

This agreement likely occurred when Raskolnikov was formulating his article on the permissibility of bloodshed according to conscience, or while he lay on his couch fantasizing about murder. Perhaps it happened even earlier, when he allowed what Dr. Zosimov describes as "furious, exceptional vanity" to take root within him.

Terrified, Raskolnikov attempts to flee, only to find a silent crowd lurking in the hallway, on the stairs, and downstairs— “everywhere was full of people, one head after another, all looking at him—but all pressed back, silently waiting…”

Literary reference:

The dream about the old woman bears a striking resemblance to the protagonist's dream in Hugo's "The Last Day of a Condemned Man." The similarities are numerous—the structure, the room-by-room search, the living room's appearance, and the old woman's hiding place in the corner.

Awakening from this terrible nightmare, Raskolnikov sees Arkady Ivanovich Svidrigailov standing in the doorway of his tiny room. Svidrigailov is also a rather unpleasant person. As you've already guessed from the description of his cane, it was he who was following Sonya. And now he has even entered the room of a sleeping person without permission.

Tell me, did you enjoy the first half of the novel?

PS

Dostoevsky often employs "semantic excess" in relation to the protagonist. He constantly adds details that perplex the reader and seem more complex than they should be. This is manifested in Raskolnikov's constant judgments and his inconsistency. Dostoevsky always had great faith in his readers. He even wrote in his drafts:

Please be careful and, if you can, let us know how you are doing.

The tradesman being described as having sprung from the "underground" reminds me of another Dostoevsky character. Maybe he's a ghost or an allegory, rather than a person?

I remember when Raskolnikov first visits the old woman's house, and later when he kills her, there's a ray of sun struggling to enter the room. I think it's significant that the events of the book happen during the time of white nights, when the sun is always present, like an eye watching Raskolnikov discreetly, a higher presence that follows him but can't quite reach him yet. Instead the moon, who has not been there in real life, is engulfing the whole house in the dream, as if he's in a different dimension altogether.

The faceless crowd laughing at him reminded me of all the heads nosing in the room when Marmeladov died. Maye the real demon is people's indifference?

I hope the floods are under control by now, Dana. Hang in there! And as always, your illustrations are wonderful.