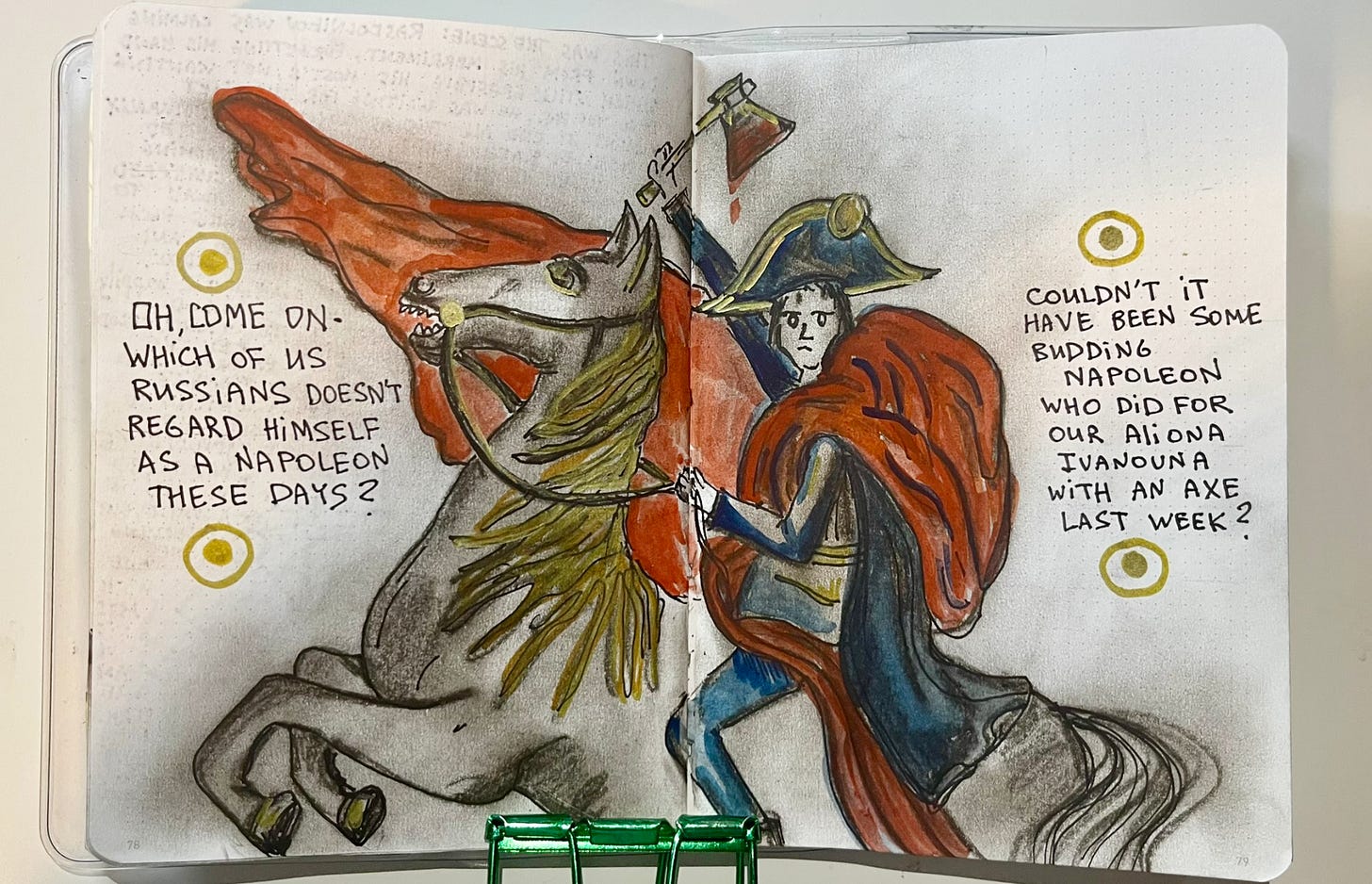

3.5 “Couldn’t it have been some budding Napoleon who did for our Aliona Ivanovna with an axe last week?”

This is the first meeting between detective Porfiry Petrovich and Raskolnikov. Now the game begins of who will outsmart whom. Will Porfiry be able to punish Rodion without having clear evidence?

Hello, Dostoevsky enthusiast!

List of articles by chapters you can find here

Reading schedule is here.

The discussion of the novel is completely free for my subscribers. Please subscribe and share the articles and your thoughts in the comments.

This chapter is particularly complex, diverging significantly from previous ones with its nearly uninterrupted philosophical discussions and minimal action. I've rewritten this summary multiple times, struggling to condense its lengthy content. My aim has been to distill the most crucial points in a simple manner. For those interested in exploring the numerous detailed aspects, I invite you to discuss them in the comments or group chat.

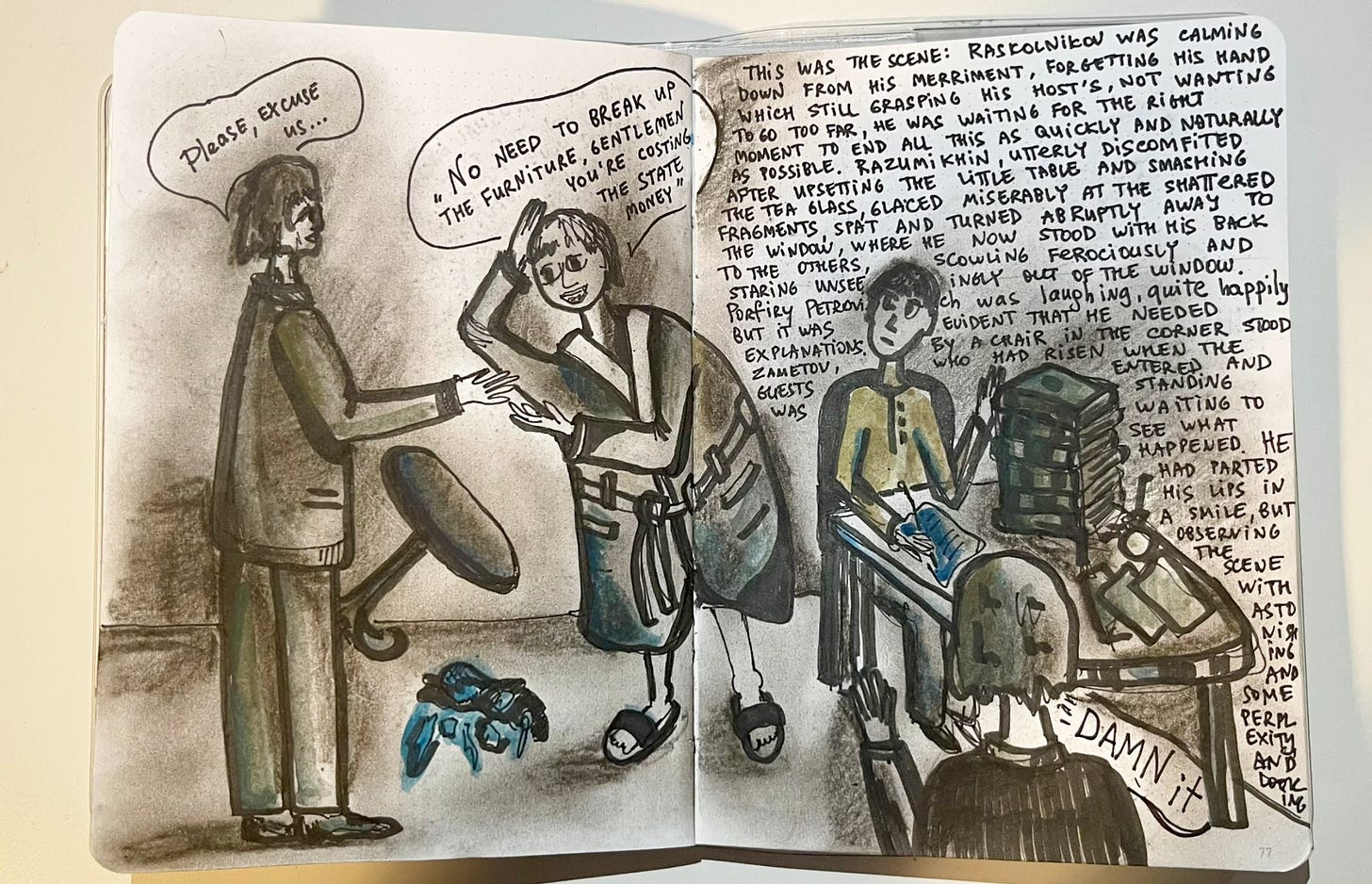

The scene unfolds in Porfiry Petrovich's personal apartment, evident from his attire—a dressing gown. Present is Zametov, the police station secretary whom Raskolnikov encountered in chapter 2.1 when summoned for unpaid rent and then he also talked to him at the "Crystal Palace" tavern (2.6), where he directly said that he had killed the old woman, but then laughed it off. Into this setting, Raskolnikov and Razumikhin arrive to meet Porfiry Petrovich.

Who is Porfiry Petrovich?

Porfiry Petrovich is an investigator assigned to the murders of Alyona Ivanovna and Lizaveta. We've already gleaned much about the suspects and evidence from Razumikhin's earlier accounts. Razumikhin, being Porfiry Petrovich's relative, has learned a great deal from him. It seems that, at the time, there was little regard for the confidentiality of the investigation.

Why Porfiry Petrovich lacks a surname, which never appears in the novel. Petrovich is his patronymic, indicating he is Pyotr's son.

Porfiry Petrovich—unique among "Crime and Punishment's" main characters—has no surname. This peculiarity emphasizes both his isolation and enigmatic nature in the novel, while also conveying an intimate, "homely" portrayal of Porfiry, who conducts his investigation without leaving his apartment.

The first phrase with which Porfiry greets Raskolnikov is a reference to Gogol's "The Inspector General".

Porfiry Petrovich paraphrases the famous words of the Governor from Gogol's "The Inspector General": "Of course, Alexander the Great was a hero, But that's no reason for breaking chairs. The state must bear the cost." This opening remark seems to reflect Porfiry's initial attitude towards Raskolnikov's crime. Notably, such Gogolian moments recur whenever Raskolnikov encounters Porfiry Petrovich.

"The Inspector General," a comedy by Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol, satirizes corruption, human vices, and fear of authority. It mocks officials who mistake a passing adventurer for an important state inspector, exposing their foolishness and corruptibility.

Dressed in a dressing gown, Porfiry makes a pleasant first impression. He laughs genuinely alongside Raskolnikov, who forces laughter, inadvertently humiliating his friend.

Stages of the investigation

Porfiry immediately deduces that the murderer was someone familiar to the old pawnbroker—someone she willingly opened the door for. This is why he has already questioned all the pawners, with Rodion being the last.

In reality, the detective has only three pieces of circumstantial evidence against Rodion, and no direct proof. He must work with the following:

Rodion was a pawner who personally knew the old woman. This is a fact. Porfiry knows the dates of Raskolnikov's visits to her.

The article outlining Rodion's theory. He wrote this piece six months ago, but it was published recently. We can infer that the desire to kill someone and prove his theory arose much earlier, perhaps a year ago, partly influenced by the death of his fiancée. The overheard conversation in the tavern merely determined his victim—Alyona Ivanovna.

Rodion's peculiar behavior, specifically his confession to Zametov about the murder. Whether a bluff or not, it's suspicious.

That's the extent of it. We know that no one witnessed Raskolnikov at the old woman's place on the day of the murder.

The beginning of the psychological game

Porfiry needs to push Rodion towards self-incrimination. During their first meeting, Porfiry almost drives Raskolnikov out of his mind by hinting at his knowledge of the crime. To provoke Raskolnikov, he raises the topic of crimes, discussing with Razumikhin a theory popular in "progressive" circles — environmental theory. According to this theory, crimes are caused only by "abnormalities in social structure" and the environment - eliminate these, and the causes of crimes will disappear on their own. This new idea, described by Chernyshevsky in his work "The Anthropological Principle in Philosophy" (1860), was considered revolutionary at the time.

"Under certain circumstances, a person becomes good, under others - evil".

Today, this theory may seem naïve, but it was taken seriously at the time. It essentially became the foundation for socialist revolutions, leading to crimes and bloodshed that far surpassed those of "everyday" crimes. This theory is as dangerous as Raskolnikov's, both potentially resulting in widespread violence.

The astute Porfiry endorses the "environmental theory" to provoke discussion between Razumikhin and Raskolnikov. Raskolnikov then elaborates on his own theory: "extraordinary" individuals have the right to transgress societal norms for the sake of great ideas, even if it demands sacrifices. He contends that exceptional people often become criminals by violating outdated laws. In his view, these "extraordinary" individuals drive progress, guiding humanity towards a better future. He posits a constant struggle between them and "ordinary" people until the emergence of an ideal society—the New Jerusalem (Revelation of St. John the Theologian, 21:1-3).

Raskolnikov's Theory and Napoleon

Raskolnikov expounds his theory in detail throughout several episodes of the novel. At its core, the theory posits that all people fall into two categories:

"Ordinary people"—unremarkable individuals whom Raskolnikov terms "material." These people are obedient and conservative.

"Extraordinary people"—outstanding individuals or "Napoleons," who drive progress, enjoy greater freedoms, and set their own moral boundaries.

While it's true that at any given time, society comprises a few geniuses, several dozen talented individuals, and the "ordinary" masses, Raskolnikov overlooks a crucial point. He fails to consider that exceptional people can exist in various fields without necessarily resorting to crime to advance humanity. Instead, he fixates on the notion that extraordinary individuals have the right to transgress laws, specifically by sacrificing others' lives.

Razumikhin astutely challenges Rodion:

"But shouldn't these truly ingenious individuals, those granted the right to kill, suffer at all for the blood they've spilled?"

Raskolnikov retorts:

"Why use the word 'should'? There's no permission or prohibition here. Let them suffer if they pity their victims... Suffering and pain are essential for a broad mind and a deep heart. I believe truly great people must experience profound sadness in this world," he added pensively, his tone shifting from the conversation's earlier tenor.

Let's reflect on this further. Raskolnikov's assertion that figures like Napoleon have "not a body, but bronze" and lack reflection on their victims, carelessly "spending" countless lives, reveals a deeper truth. Unconsciously, Raskolnikov doesn't truly consider them great. For him, true greatness lies in those who possess both a broad consciousness and a deep heart—individuals capable of profoundly experiencing the world's imperfections and the consequences of their actions. This perspective represents a novel framing of the problem, introduced by Raskolnikov and, through him, by Dostoevsky himself.

To become Napoleon, one must forsake the heart. Napoleon himself acknowledged this:

"Two different people live within me: the man of the head and the man of the heart. Don't think that I don't have a sensitive heart, like other people. [...] But from my early youth, I tried to silence this string, which now no longer produces any sound in me."

It's telling that in Raskolnikov's theory, Napoleon and the other "extraordinary" figures he cites belong to disparate categories. He invokes these names merely to lend credibility to his "theory," which ultimately seeks not to benefit humanity, but to gain power over it. Raskolnikov's fixation on Napoleon alone underscores this ulterior motive.

Porfiry's Traps and Raskolnikov's Behavior

Raskolnikov is prepared to engage in a battle of wits with the detective, meticulously weighing his words, calculating his responses, and remaining suspicious. The reader is drawn into his intense focus through his inner monologue. Porfiry needs concrete evidence to implicate Raskolnikov. He attempts to ensnare him, first by trying to determine if Raskolnikov views himself as "extraordinary"—someone capable of "stepping over the line."

To further provoke Raskolnikov and elicit more revealing statements, Porfiry mockingly challenges the theory of categorizing people:

"But tell me this: how does one distinguish these extraordinary people from the ordinary ones? Are there some kind of signs at birth?"

Porfiry, proving himself an exceptional investigator, aims not only to expose Raskolnikov but also to offer him paths to redemption. His probing questions about faith are far from casual:

Does he truly believe in the New Jerusalem?

Does he believe in God?

Does he believe in the resurrection of Lazarus (as recounted in the Gospel of John)?

Curiously, Raskolnikov arrives at Porfiry's intending to feign vulnerability through a pseudo-confession. He planned to "sing Lazarus" (as mentioned in the previous chapter). This expression alludes to the biblical parable of the rich man and poor Lazarus (Gospel of Luke, 16:19-31). In life, Lazarus lay covered in sores at the rich man's gate, yearning for fallen crumbs from the rich man's table. After death, the rich man, now in hell, begged the heavenly Lazarus to ease his torments.

However, Porfiry swiftly steers the conversation back to reality: poverty isn't the primary motive for Raskolnikov's crime, nor did it warp his destiny. Porfiry reminds him of another Lazarus—the one Christ resurrected, demonstrating His mastery over life and death.

Which Lazarus resonates more with Raskolnikov? How will he respond?

Porfiry then employs an indirect tactic, posing a cunning question about painters, hoping to catch Raskolnikov admitting his presence at the old woman's apartment on the day of the murder. Raskolnikov, however, deftly sidesteps this trap.

Given Rodion's reflections and responses, do you think Porfiry's suspicions have intensified, or has Rodion managed to outwit him?

When Porfiry Petrovich said "let me ask just one little question," that was SUCH a Peter Falk moment, my second read-through had a whole other flavor thanks to that mental image alone.

My experience with Dostoevsky has been such a roller coaster compared with Tolstoy's smooth sailing, I hate him and love him and hate him and love him. Just like with Raskolnikov himself.

Those words Porfiry nudged out of him at the end stood out to me too, "Truly great people, I think, must feel great sadness for the world." In all his delusions of grandeur, I do believe that one thing completely, Rodion is suffering and has been suffering for a long time, the state of the world (judging by how suffocating St. Peterburg is) must seem unbearable. I wouldn't be surprised to find out a lot of lonely young boys today can still relate to Rodion, and just like him, have come to all the wrong conclusions.

(Sorry I'm uploading all my ramblings together Dana, this week I really bit more than I could chew, I did read the chapter but had no time to comment them)

A bit late for the discussion,but just a couple of comments. This was such an engrossing chapter and such a clever point and counterpoint in the dialogue. This may sound strange, but I found it a bit comical; I could imagine it as some sort of witty farce. Even Rasumikhin asks if their talk is a joke: "Are you pulling each other's legs, or aren't you?"

Of course, though it is deadly serious for both men, and I think Raskalnikov wins this round. What I found interesting is that it is Razumikhin who divines that Raskalnikov's argument for justifiable killing is put "on grounds of conscience." Isn't this the way Raskalnikov originally rationalised his killing of the old woman, that she was somewhat of a social pariah, or something to that effect? It seems to me that, at bottom, it is the murder of Elizabeta, which is barely mentioned, that is the source of Raskalnikov's now agonised state.