3.4 “Look here, brother, I’m… Oh, you really are a swine!”

Seven people crowd the small room. After they leave, a mysterious man follows Sonya, while Rodion taunts Razumikhin—a strategic ploy to avoid suspicion.

Hello, Dostoevsky enthusiast!

List of articles by chapters you can find here

Reading schedule is here.

The discussion of the novel is completely free for my subscribers. Please subscribe and share the articles and your thoughts in the comments.

The chapter continues the previous scene in Rodion's cramped room. (Its smallness is striking—how do they all fit?) Six people are present: Raskolnikov himself, his sister Dunya, his mother Pulkheria Alexandrovna, his friend Razumikhin, the doctor Zosimov, and the house servant Nastasya. Then a seventh person enters—Sonya (full name: Sophia Semyonovna Marmeladova).

Sonya steps into this overcrowded room where six strangers intently observe her. It's an intimidating situation, particularly as she's unfamiliar with Rodion. While he has already idealized her as a saintly martyr and dwelled on thoughts of her, she knows nothing about him. Yet, Luzhin has already conveyed his opinion of her in a letter.

This new arrival dramatically shifts the room's dynamic. Let's consider Sonya's perspective. Imagine being in Sonya's position: an 18-year-old who has just lost her second parent. She's left with a stepmother who drove her to prostitution and three step-siblings. The burden of caring for these three lives now rests on her fragile shoulders, as Katerina Ivanovna seems incapable of providing for them. To compound matters, Katerina is gravely ill—in the chapter detailing Marmeladov's death, she coughs up blood in the doctor's presence. Sonya's circumstances are truly desperate.

The Coffin Motif

Sonya arrives to invite Rodion to her father's funeral service and wake—events financed, ironically, by Rodion's mother. She had sent her son money that was hard to come by, which he promptly gave away. We learn that Marmeladov's body still lies in their apartment, exposed to the sweltering July heat.

The mention of Marmeladov's coffin stirs something in Raskolnikov. Recalling his mother's recent comment, he unexpectedly asks Sonya:

"Why are you looking at my room like that? My mother says it looks like a coffin too."

"You gave us everything yesterday!" — Sonya suddenly replied in a strong, quick whisper, her eyes downcast. Her lips and chin quivered. Long struck by Raskolnikov's poor living conditions, these words burst out unbidden. A silence followed. Dunechka's eyes brightened, and even Pulkheria Alexandrovna gave Sonya a friendly look.

The scene's surface meaning is clear: Sonya is moved by how someone living in such poverty could give away his entire savings—a considerable sum equal to her father's monthly salary—to strangers. Her heartfelt gratitude touches Dunya and Pulkheria Alexandrovna. In the ensuing silence, it's as if a quiet angel passes by. But do we always fully grasp the meaning of our own words? Don't they often carry significance we fail to notice?

Through Sonya's unconscious words, the wisdom of existence answers Raskolnikov: Yes, your room resembles a coffin, reflecting your mortal sin, yet you still aided strangers in need. Herein lies the promise of your possible salvation.

Dunya — A Woman of True Character

Among all present, only Dunya treats Sonya with genuine respect, refraining from judgment. This interaction highlights Dunya's intelligence and tact. Rodion might have behaved similarly had he not been consumed by his dark thoughts.

"But Avdotya Romanovna, as though waiting her turn, on passing Sonya with her mother, made her a careful, courteous, and full bow."

Pulkheria Alexandrovna, however, displays a peculiar attitude towards young women, including Sonya. Despite the absence of a romantic connection between Sonya and Rodion, Pulkheria already expresses disapproval. This mirrors her reaction to the girl Rodion once wished to marry—unseen and unknown, yet disliked. Even with the mere hint of acquaintance between Sonya and Rodion, Pulkheria's aversion is evident. One might wonder what term describes a mother who instinctively dislikes any girl her son shows interest in.

"You know, Dunya, looking at you both, you're his perfect portrait, and not so much in face as in soul: you're both melancholic, both gloomy and quick-tempered, both haughty and both generous..."

Dunya, once again, demonstrates her empathy and respect for others.

"Who cares what he writes! They talked about us too, and wrote about us, have you forgotten? And I'm sure she's... wonderful and that it's all nonsense!"

Dunya stands out as the most agreeable and level-headed character thus far. Her behavior, words, and judgments have been consistently admirable. It's particularly noteworthy that Dostoevsky crafted Raskolnikov's sister—a female character—to be entirely positive and likable.

The Mysterious Man Following Sonya

Some readers may already know this man's identity, while others will discover it later. For now, the mystery remains.

This scene stands out as one of the novel's most unsettling, with palpable suspense. Who is this enigmatic figure trailing a young woman, and what are his intentions in following her home?

How do you perceive this character? What might have prompted him to follow Sonya after overhearing Raskolnikov's name?

His eerie exclamation "Bah!" (sometimes translated as "Well!"), repeated throughout the pursuit, adds another layer of unease to Dostoevsky's writing. The original Russian "Bah!" is particularly chilling—an excited utterance devoid of inherent meaning. Yet this man seems unable to contain his strange delight and astonishment as he shadows Sonya.

Dostoevsky's detailed description of the man and narration of their journey, without revealing his name, masterfully heightens the sense of mystery.

The Detective Game Begins

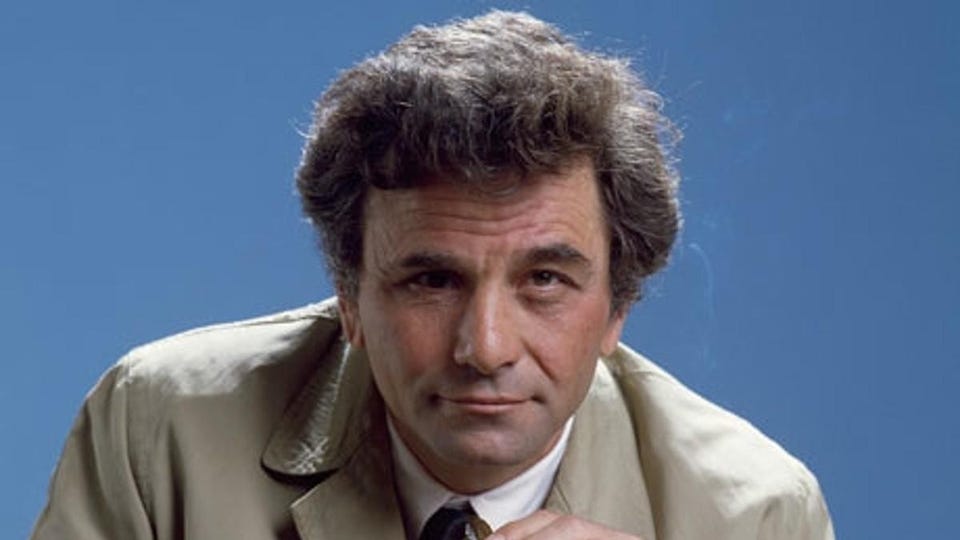

Rodion seems to have regained his composure, once again donning the mask of innocence. He meticulously plans his next move: visiting Porfiry Petrovich—the novel's Columbo, a detective with keen insight into criminal psychology.

For the uninitiated, Columbo is a TV detective series (1968–1978) with a unique twist. Unlike typical crime shows, in this series the crime was shown to viewers at the very beginning, and they immediately knew the killer. The audience then watches as the astute Detective Columbo methodically unravels the case, often using clever psychological tactics to expose the culprit. This approach is very close to what will unfold in the books. I think this series was inspired by the book.

Porfiry Petrovich emerges as a central character for the latter half of the novel. We're about to witness a battle of wits between the criminal and the detective—who will outwit whom?

Rodion resolved to declare himself a client of the murdered pawnbroker. Though indifferent to the pawned items, he concocted a plausible story—his father's pawned watch might be precious to his recently arrived mother. For Raskolnikov, the reasons aligned conveniently, as if scripted for a play. He recalled pawning two items: a ring a month before the murder, yielding 2 rubles, and his father's watch—pawned in the novel's opening chapter—for 1 ruble and 15 kopecks.

Sing the Song of Lazarus

"I'll have to sing the song of Lazarus to him too," he thought, turning pale and with his heart pounding. "And sing it as naturally as possible. The most natural thing would be to sing nothing at all. Emphatically sing nothing! No, that would be unnatural again... Well, we'll see how it turns out... we'll see... right now... is it good or bad that I'm going? The moth flies to the candle itself. My heart is pounding—that's what's bad!"

"To sing the song of Lazarus" is an idiom meaning to feign poverty, complain, evoke pity, or beg. In Rodion's thoughts, it refers to his plan to pretend, hiding behind the mask of a "poor and sick student, oppressed by poverty."

The expression originates from a folk spiritual verse titled "Two Lazaruses," a literary adaptation of the biblical parable of the rich man and Lazarus (Luke 16:19-31). You can read the parable here: where various translations and languages are available.

Beggars seeking alms would sing this "Two Lazaruses" verse in a particularly plaintive manner. To hear how it sounded, you can listen to theater artists performing it in Russian:

Interestingly, Raskolnikov's reference to the "poor Lazarus" foreshadows Porfiry Petrovich's question in the next scene about belief in the resurrection of "Lazarus of four days"—though these are distinct stories.

Rodion's Calculated Teasing

Rodion resorts to mocking his friend for personal gain—a calculated move to appear relaxed before Porfiry and to distract Razumikhin.

"Raskolnikov laughed so much that he seemed unable to contain himself, and they entered Porfiry Petrovich's apartment still laughing. This was exactly what Raskolnikov wanted: from the rooms, one could hear that they had entered laughing and were still guffawing in the hallway."

Yet, Raskolnikov alone was truly laughing.

He taunts Razumikhin, dubbing him "Romeo"—an allusion to Shakespeare's star-crossed lover. Rodion insinuates that Razumikhin has fallen for Dunya, constantly sighing and blushing in her presence.

Razumikhin's reaction, however, is genuine. Caught off guard by his friend's mockery, he becomes increasingly irate. Furious and enraged, Razumikhin retorts by calling Rodion a "Swine"!

In this agitated state, they arrive at the police office.

The next chapter is very important but also quite challenging—it's lengthy and filled with philosophical monologues. We'll meet Porfiry Petrovich and learn a great deal about Raskolnikov's ideas.

What are your thoughts on this chapter? Did any moments stand out to you, either positively or negatively?

Happy reading!

I loved to see arch Colombo when I was young! I can’t wait to watch this battle of wills unfold. I found this article from the makers of Colombo about creating the character and show. They did, indeed, use Crime and Punishment as inspiration after studying it in college. http://www.columbo-site.freeuk.com/created.htm

There would be so much to discuss about this chapter! But I’ll just point out the incredible and seamless changes in point of view: we see through the perspectives of Sonya, both mother and daughter, Sonya again, Svidrigailov, and finally, Rodion and Razumikhin. These shifts in perspective are easy to follow, but in the hands of a less skillful writer, they could have been quite confusing!