3.3 "What a liar! Are you in a sensitive mood today or something?"

Six people are crammed into a room the size of a closet. Rodion behaves like an automaton, speaking as if reciting a memorized script. Even his own mother is afraid of him.

Hello, Dostoevsky enthusiast!

List of articles by chapters you can find here

Reading schedule is here.

The discussion of the novel is completely free for my subscribers. Please subscribe and share the articles and your thoughts in the comments.

I apologize for the delay in the schedule. Today I will give a few points for chapter 3.3, and tomorrow chapter 3.4 will be released, and on Thursday - 3.5. Due to my illness, it's a bit rushed, but in fact, the chapters themselves are interesting and quite easy to read. We have several female characters appearing at once, which give the novel more lines of thought.

A brief reminder of what happens in chapter 3.3.

Rodion's sister Dunya, his mother Pulkheria Alexandrovna, accompanied by Razumikhin, come in the morning to visit Raskolnikov. Doctor Zosimov is already sitting in his room. And so in his cramped room, which is the size of a closet, 6 people are sitting and standing - Nastasya is also there, the housekeeper who works for Rodion's landlady and who often helps him, despite the fact that he pays nothing.

Nastasya's role is much bigger than it seems. After re-reading the novel, I began to notice how much she is present throughout, although she seems inconspicuous. Translated from Greek, the name Nastasya, Anastasia means "returning to life". A small reminder of how many times she brought Rodion back from the verge. She brought him food, tea, soup, almost every day that we observe the plot.

The story began on July 7, and today is the 15th. Together with Razumikhin, she helped when Rodion was sick and delirious, with clothes (she might have even gone with Razumikhin to buy them). It was also she who visited him after his second dream or hallucination, in which Rodion thought that a policeman was beating his landlady. And she said these words, that blood is screaming in him. And now she is also part of this "family" gathering.

Light and Torment

"However, even this pale and gloomy face was illuminated for a moment as if by light when his mother and sister entered, but this only added to its expression, instead of the former melancholy distraction, a kind of more concentrated anguish. The light faded quickly, but the torment remained"

Light and torment are the harbingers of salvation for the fallen. When Raskolnikov's mother and sister visited him, he appeared slightly better than the day before, yet remained tormented. Dostoevsky observes that he "lacked some kind of bandage on his arm or a taffeta cover on his finger to complete the resemblance to a man with, for instance, a painfully festering finger or an injured hand."

Raskolnikov endures the anguish of a guilty conscience—a pain that, while currently unproductive, is nonetheless spiritual in nature. He bears no visible, physical marks of damnation. In Dostoevsky's works, tangible signs invariably correspond to something intangible within a person's psyche.

Detachment from the World

Recall how, before succumbing to delirium, Raskolnikov seemed to sever himself from the world, as if with scissors, while on the bridge. Though he survived the fever, he remains mentally distant.

Cast out by society, Raskolnikov exists in a limbo-like state, paralyzed by indecision. He alone must summon the inner strength to choose his path—towards God or the devil. Yet, to remain frozen in this terrifying void is unbearable, unthinkable. Those once dear to him have become strangers; there's no shared language between them. And without a common tongue, words lose their meaning, becoming lifeless.

Though outwardly communicating with those once close and dear, Raskolnikov can only acknowledge his profound isolation—a cursed loneliness that has severed him from all living things.

"Here you are... it's as if I'm looking at you from a thousand miles away... And devil knows why we're talking about this!"

During this conversation, Raskolnikov realizes that his past experiences seem to have occurred "in another world." Now, he views current events "as if from a thousand miles away," and everything around him feels unreal. Raskolnikov intuitively senses that the true origins of these events lie in a realm beyond the physical.

This profound concept will resurface in Dostoevsky's later novel, "The Brothers Karamazov." There, he will express the idea that "The roots of our thoughts and feelings are not here, but in other worlds."

In this otherworldly state, Raskolnikov suddenly spoke of his deceased fiancée, his beloved, reminding us that he loved her. Why does Dostoevsky abruptly reveal this tale of ill-fated love, seemingly insignificant until now? In the previous chapter, his mother, sister, and Razumikhin reminisced about her in Rodion's absence. Now, Rodion himself brings her up unprompted. This recollection isn't random. Does she represent a beacon of Light for him? Or a source of Torment?

Is Rodion Human?

The question "Is he human?" recurs throughout the novel. It echoes Marmeladov's cry about Sonya and Razumikhin's article asking, "Is a woman human?" Here, "human" transcends mere biological classification—it embodies divine creation, demanding correspondence to that ideal.

"Is he answering us out of obligation?" thought Dunechka, "he reconciles and asks for forgiveness as if he's performing a service or reciting a memorized lesson."

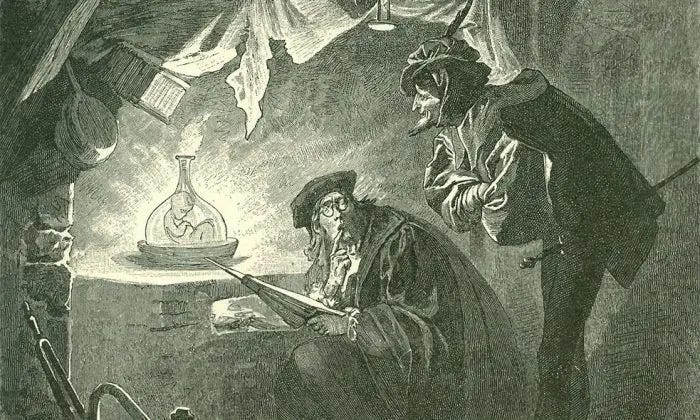

Rodion's behavior resembles that of a robot or homunculus. Razumikhin previously raised this "homunculus" question when encountering Rodion outside the "Crystal Palace" tavern (2.6 chapter). If you've read Constance Garnett’s translation, you might have missed a crucial phrase (As inquired about this in the comments, I'll take this opportunity to revisit the topic).

The original Russian states: "You're made of spermaceti ointment, and instead of blood you have whey!" Pasternak Slater's version renders it as: "You're all made of whale oil, with whey instead of blood!"

This reference alludes to an artificial human—the method by which "homunculi" were supposedly created. In essence, Raskolnikov is portrayed as an unnatural being. Now Dunya, his sister, is also contemplating how unnaturally Rodion is behaving. He responds mechanically, as we might say, like a robot. However, before the invention of robots, people referred to other artificial entities—such as the homunculus. This concept is far more sinister, as homunculi were believed to be created with blood.

Hatred

"He's lying!" he thought to himself, biting his nails in anger. "The proud creature! She won't admit that she wants to be charitable! Oh, such base characters! They even love as if they hate... Oh, how I... hate them all!"

In the conversation with his mother and sister, Raskolnikov's emotions escalate to hatred, as he habitually shifts blame onto others. He fails to consider a crucial question: why did he commit the crime for their sake?

Could it be that this situation stems from Raskolnikov's refusal to depend on their kindness, preferring instead for them to rely on his self-sacrifice?

When he accuses his sister of committing a vile act by agreeing to marry Luzhin, Dunya retorts: "If I ruin anyone, it will only be myself... I haven't killed anyone yet!.." Ironically, Raskolnikov's attempts to lecture others backfire, turning into a metaphorical axe pointed at his own face. His inclination to accuse those around him invites swift retribution, regardless of the other person's intentions.

Love manifesting as hatred—this paradox drives the aspirations of excessively proud individuals. Raskolnikov dissects his sister's motives, oblivious to the fact that he's inadvertently defining himself in the process. Yet, he exposes Dunya's situation with brutal clarity:

"You're lying, sister... You can't respect Luzhin: I've seen him and talked to him. Therefore, you're selling yourself for money, and therefore, in any case, you're acting basely..."

Coffin

What a terrible apartment you have, Rodya, just like a coffin

The recurring comparison of the protagonist’s room to a "coffin" is a key element in the novel's system of biblical allusions. This imagery supports a crucial parallel in Dostoevsky's artistic vision between Raskolnikov and Lazarus, who was dead for four days before being resurrected. We'll explore the Lazarus connection in more depth later in the novel, though we've touched on it several times in our discussions of previous chapters.

However, in the system of Gospel allusions, the comparison of Raskolnikov's room to a "coffin" takes on a different, more sinister meaning. This demonic connotation is echoed in the Gospel of Luke (Luke 8:27):

"...When Jesus stepped ashore, he was met by a demon-possessed man from the town. For a long time this man had not worn clothes or lived in a house, but had lived in the tombs."

Also in Mark (Mark 5:3-5):

This man lived in the tombs, and no one could bind him anymore, not even with a chain. For he had often been chained hand and foot, but he tore the chains apart and broke the irons on his feet. No one was strong enough to subdue him. Night and day among the tombs and in the hills he would cry out and cut himself with stones.

Notably, in Mark's account, alongside the motif of "living in the tomb," we find the motif of "stone" ("cut himself with stones"). This stone imagery serves as a powerful "figurative accompaniment," which plays a significant role in "Crime and Punishment" as an element of its Petersburg poetics. Petersburg, after all, is a city of stone with sparse greenery. We can also recall the large, dirty stone under which Rodion concealed all the stolen items.

"What a terrible thought you've just expressed, mama" he suddenly added, smiling strangely.

It wasn't the coffin-like apartment that led Raskolnikov to criminal thoughts, but his long-standing pride. This pride had nurtured these thoughts, settling the future murderer in a room that mirrored his evil spiritual state and the essence of his crime. Whether or not Raskolnikov fully grasped what he meant to express, his strange smile perfectly matched Pulkheria Alexandrovna's unsettling observation. Such smiles and thoughts could make even a moderately sensitive person's hair stand on end.

Raskolnikov felt as if he was plummeting into a void of his own making.

He was determined to have his way, insisting that Dunya immediately agree to break off her engagement with Luzhin. Why did Raskolnikov want this so urgently? Primarily because he vaguely sensed his metaphysical guilt towards his sister: if not for his long-harbored evil thoughts and spiritual rebellion, Dunya would never have encountered either Luzhin or Svidrigailov.

Fear

"What, are you all afraid of me?" he said with a distorted smile. "That is indeed true," said Dunya, looking directly and sternly at her brother. "Mother even crossed herself in fear when coming up the stairs."

The pervasive awkwardness in the room, dialogues, and behavior stems primarily from fear. Rodion's family fears him due to his inappropriate behavior, but they also fear for his health and well-being. They worry about their own futures—what might happen if something befalls Rodion or if the engagement falls through. Their fears are compounded by financial insecurity and uncertain prospects.

Everyone harbors some form of fear.

Rodion fears the discovery of his crime. Yet, paradoxically, he also dreads that no one will uncover it, forcing him to bear this burden indefinitely—a weight he struggles to shoulder.

While fears can often be assuaged by the presence of a loving individual, the current atmosphere of hatred, inhumanity, suspicion, and ultimatums only intensifies the fear. I began by stating that Light and Torment are key to the salvation of the fallen. However, when light fades, only torment persists. In this novel, you can sense this torment permeating every line.

NB Literary reference

Crevez, chiens, si vous n'êtes pas contents!

A French phrase appears in the novel, like a saying: "Crevez, chiens, si vous n'êtes pas contents!" The translation is "Drop dead, [you] dogs, if you aren't satisfied!" This is a slight paraphrase of a line from Victor Hugo's novel "Les Misérables," which Dostoevsky read upon its publication in 1862.

In Chapter "A Rose in Misery" of Hugo's novel, the young student Marius receives a visit from his neighbor Jondrette's emaciated daughter. During their conversation, she tells him:

"Do you know what it will mean if we get breakfast today? It will mean that we shall have had our breakfast of the day before yesterday, our breakfast of yesterday, our dinner of today, and all that at once, and this morning. Come! Parbleu! if you are not satisfied, dogs, burst!"

However, this omits a crucial detail that follows when Marius realizes how much worse off the Jondrettes are than he:

By dint of searching and ransacking his pockets, Marius had finally collected five francs sixteen sous. This was all he owned in the world for the moment. "At all events," he thought, "there is my dinner for today, and tomorrow we will see." He kept the sixteen sous, and handed the five francs to the young girl.

This scene presents a striking parallel to Raskolnikov's actions in relation to money and giving it out to people around him.

What emotions did you experience while reading this chapter?

Did you feel the awkwardness, as if you were in this cramped room?

Did you feel the urge to escape as quickly as possible?

The plot thickens as a seventh person enters the room. In tomorrow's article about chapter 3.4, we'll discover who this newcomer is and whether their presence intensifies the awkwardness or perhaps alleviates it.

This might be a bit of a stretch, but I’ve been thinking... Rodion is often surrounded by blood—on his clothes, the floor, or when he's washing it off. But inside, it feels like there’s no blood in him. He doesn’t have what blood symbolizes—love, life, warmth. While he’s dealing with crime and its mess on the outside, inside he feels empty and disconnected. It’s almost like being bloodless shows how he feels inside.

I think the void, the distance between Raskolnikov and the others, is a two-way street. I finally pinpointed what has been annoying me about Razumikhin and his "intervention": he never acknowledged Rodion's illness, he just went, nonsense, you're fine, pull yourself together!

You know what I mean? And Zosimov is doing it, and Mamenka is doing it too. This whole chapter felt so awkward and frustrating because there's this giant elephant in the room: Raskolnikov's mental state. They all see it and they're afraid to admit it.

I feel like Rodion's big revelation, that he hates his family after all, was supposed to be shocking, but a lot of people with dysfunctional or toxic families are going to relate: you meet them again after a while and think, dang, I forgot how awful they make me feel. Pulkheria Alexandrovna is an egregious example I think, she says at the end that she hates lies and deception but she's been lying the whole time, pretending that all it's fine when it's not. When she told Rodion how his being ill made HER feel bad, that is such a hurtful thing to say to a child. And she does the same to Dunya too, she acts like her daughter is about to enter a happy marriage when she's clearly not.

Dunya is the one who's treating Rodion like a human being, in this case arguing is better than pretending, you know? It's like she cares about him as a person, while P.A. cares to preserve the perfect mental image she has of his son. At least Dunya is challenging him and calling him out. I don't know, of course Rodion would feel alienated (or in this case, homunculus-ated?) if people around him are treating him like he's not even there. Am I making any sense?