Hello, Dostoevsky enthusiast!

List of articles by chapters you can find here

Reading schedule is here.

The discussion of the novel is completely free for my subscribers. Please subscribe and share the articles and your thoughts in the comments.

In discussions about the previous chapter,

expressed an interesting thought about the parallel lines that Dostoevsky creates: in 1.6 there was a conversation between students, which described in detail the theory of why the old woman should be killed. And in the previous chapter 2.6, Raskolnikov already speaks about killing the old woman from a practical perspective to the police officer Zametov, but as if in jest.In chapter 2.7, we can also see parallels with chapter 1.7. Both final chapters of the first two parts of the novel describe violent deaths. But in the chapter in Part 1, we read about how Rodion kills, and here we witness an accident and the death of Marmeladov.

If you've forgotten, Marmeladov is that alcoholic with whom Rodion conversed in chapter 1.2, Sonya Marmeladova's father. He poured out his soul to us about how difficult his fate is in the tavern.

Is Rodion involved in Marmeladov's death? He didn’t cause the accident, of course, but his actions here might’ve exacerbated the situation. Considering that for some reason he "ordered" Marmeladdov to be carried to his apartment so that his mutilated body could be seen by small children and his wife, rather than to the hospital. Most likely, 19th-century medicine wouldn't have helped him anyway, but his actions are still questionable. Can you imagine how they carried his body simply in their arms through the street and up the narrow staircase, blood flowing from it, bones broken - clearly this worsened the situation. At that moment, I completely hated Rodion - he ruins everyone's lifes, so far he only brought suffering, anxiety, and pain.

Raskolnikov enters the Marmeladovs' dwelling for the second time. The description of this squalid abode, with Katerina Ivanovna coughing and gasping for air, trying with her last strength to maintain some semblance of cleanliness and order, and the small children dressed in rags and tormented by hunger, cannot fail to break the heart of any reader who imagines that this is a picture of a hopeless existence that has lasted for many years.

Sonya

A little later, Sonia arrives in her gaudy, bright dress, which she wears while standing on the street in the evenings. Raskolnikov sees her for the first time and notices the discrepancy between her pale and sad face and her attire.

Dostoevsky describes her with sympathy (or is this just Raskolnikov's impression?):

“Sonia was a small, thin but quite attractive girl of eighteen, fair-haired and with splendid blue eyes. Out of breath with running, she stood staring at the bed and the priest. ”

This feather on the hat is emphasized twice in the description. Upon her appearance — "her absurd round straw hat with its bright flame-coloured plume."

The second time is in Rodion's memories of Sonia — "I saw another person there too… with a flame-coloured feather… but I'm getting mixed up"

The creature with the fiery feather is presented as something elevated. The feather on the hat seems to have transformed into an angel's feather. The name and Saint Sophia in the Christian tradition is considered "the personification of divine wisdom". Sonia's role in the novel can be compared to the roles played by Beatrice and Lucia combined in the "Divine Comedy". Rodion saw her and immediately understood this. We will see further how they will interact.

The death

The sufferings of Marmeladov's wife, Katerina Ivanovna, are exacerbated by the fact that, like Raskolnikov, she constantly torments herself with thoughts about the injustice of what is happening to her and her children. She is constantly tormented by the thought of the discrepancy between her noble origin and her current existence. She doesn't recall her own transgressions — for instance, how she tormented Sonia for many years (although she constantly feels guilt towards Sonia for that fateful evening), she is unable to forgive her husband even on his deathbed:

“And isn’t this a sin?’ exclaimed Katerina Ivanovna, pointing to the dying man.”

Shaken by the grief and tragedy of this family for the second time, Raskolnikov leaves them the remaining 20 rubles from the money his mother had last sent him.

He descends the stairs and thinks: "It was such a feeling as a man condemned to death might have if he was suddenly told that he had been reprieved."

We understand that these words have a special significance for Dostoevsky.

This psychological characterization has an autobiographical subtext. The writer himself experienced a similar moment on December 22, 1849, at Semyonovsky Square, as I mentioned previously.

"...I had no more than a minute to live," he wrote to his brother Mikhail that same day. "I remembered you, brother, all of yours; in the last minute, you, only you, were in my mind. I also managed to embrace Pleshcheyev and Durov, who were nearby, and say goodbye to them. Finally, they sounded the retreat, those tied to the posts were brought back, and we were read that His Imperial Majesty grants us life."

Dostoevsky later recalled his feelings after the cancellation of the death sentence like this: "I don't remember another such happy day! I walked around my casemate in the Alekseevsky Ravelin and sang, sang loudly, I was so glad for the life granted to me!" However, we should note that this describes the writer's state some time after the announcement of the pardon.

There are other memories of Dostoevsky about that day, which are considered more authentic and which were conveyed almost immediately, rather than after a time of reflection.

"Death is inevitable. If only it would come quicker... And suddenly complete indifference came over me <...> I remember some dull awareness of the inevitability of death... Precisely dull. And the news of the suspension of the execution was also perceived dully... There was no joy, no happiness of returning to life... Around me, people were making noise, shouting. But I didn't care - I had already experienced the worst. Yes, yes!! The worst..." (Dostoevsky in memoirs).

Thus, we must acknowledge that the reality of the pardoned person's experiences turns out to be much more complex and contradictory than what is reflected in this episode. And Dostoevsky in general had complex thoughts on this matter, which he partly conveyed though Rodion, where he constantly changes his emotions and feelings.

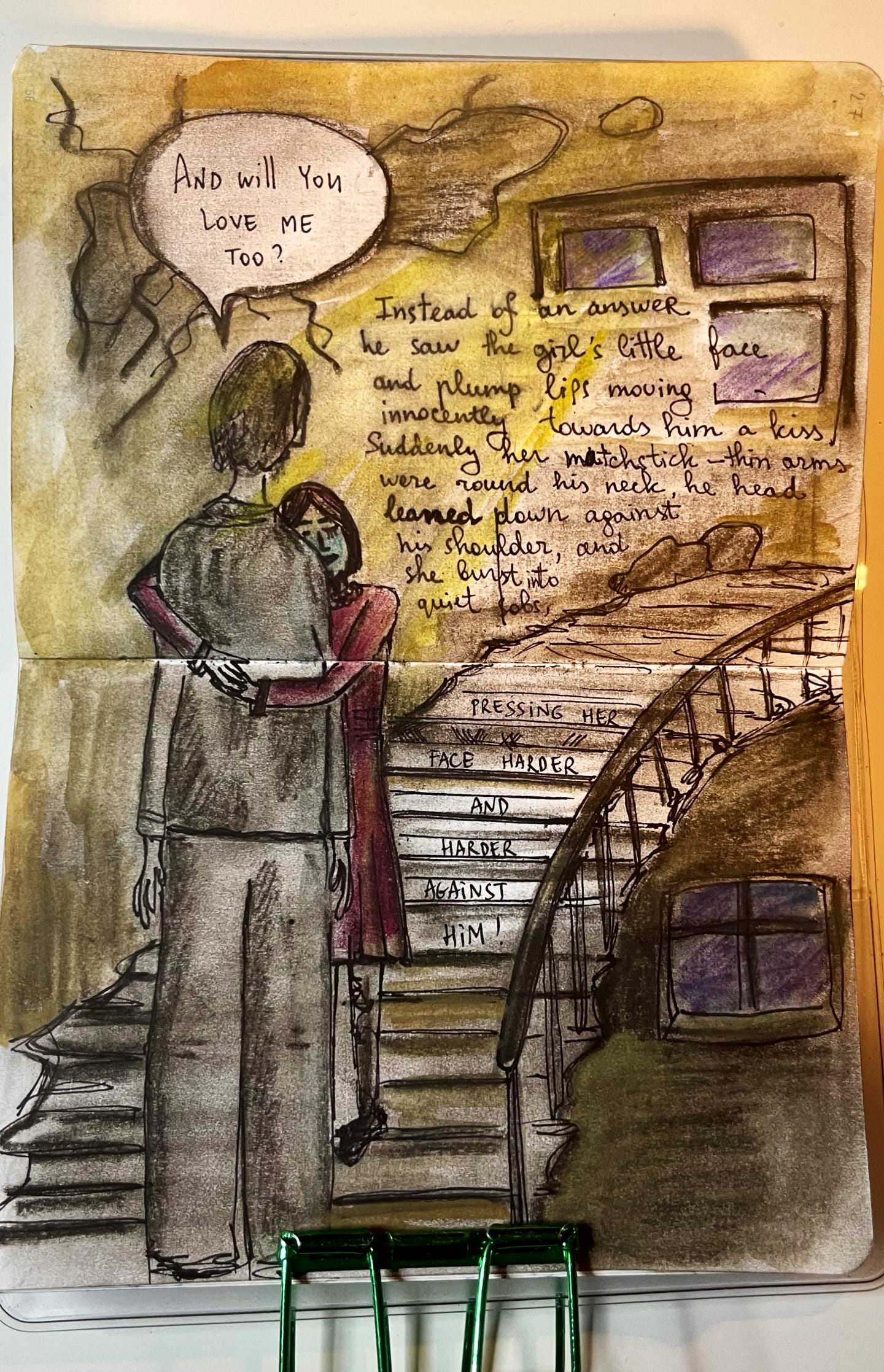

On the stairs, he is caught up by the eldest of Katerina Ivanovna's daughters, ten-year-old Polya, with words of gratitude and an invitation from her mother to come to the wake. Raskolnikov asks the child to pray for him.

“And will you love me too?’ Instead of an answer he saw the girl’s little face and plump lips moving innocently towards him to give him a kiss. Suddenly her matchstick-thin arms were round his neck, her head leaned down against his shoulder, and she burst into quiet sobs, pressing her face harder and harder against him.”

“Polechka, I’m called Rodion; pray for me sometimes too, just say “and thy servant Rodion”, that’s all.”

This first good deed after a long period of alienation from God and turning to Him gives strength to the exhausted Raskolnikov. And just five minutes later, he was again on the bridge where he had previously wanted to throw himself into the canal. But now he had different feelings.

But again, Rodion misunderstands everything that has happened - as an opportunity to continue the struggle. Cynically wishing "the Kingdom of Heaven" to the pawnbroker he killed, he thinks:

"Away with mirages, away with false fears, away with ghosts! The reign of reason and light is now and... and of will and strength... and we shall see now! Let us measure ourselves now!"

<…>

“Strength, strength is what I need; you can’t gain anything without strength; but it takes strength to win strength, that’s something they don’t know”

He added proudly and confidently as he walked off the bridge, barely dragging his feet. Pride and self-assurance were growing in him every minute. Now he thinks that he asked the girl to pray for him "just in case," and that he has already been forgiven. Rodion's relationship with God, of course, is surprising — it's roughly the same as with all of Rodion's emotions — sometimes he rejects Him, sometimes he thinks he has reconciled with Him, sometimes he asks for forgiveness, sometimes he rejects Him by killing. Here he seems to be thinking that with his own strength alone he can get through it all, and God is there… just in case. That he can rely on his own will, even though we all saw where his will led him already.

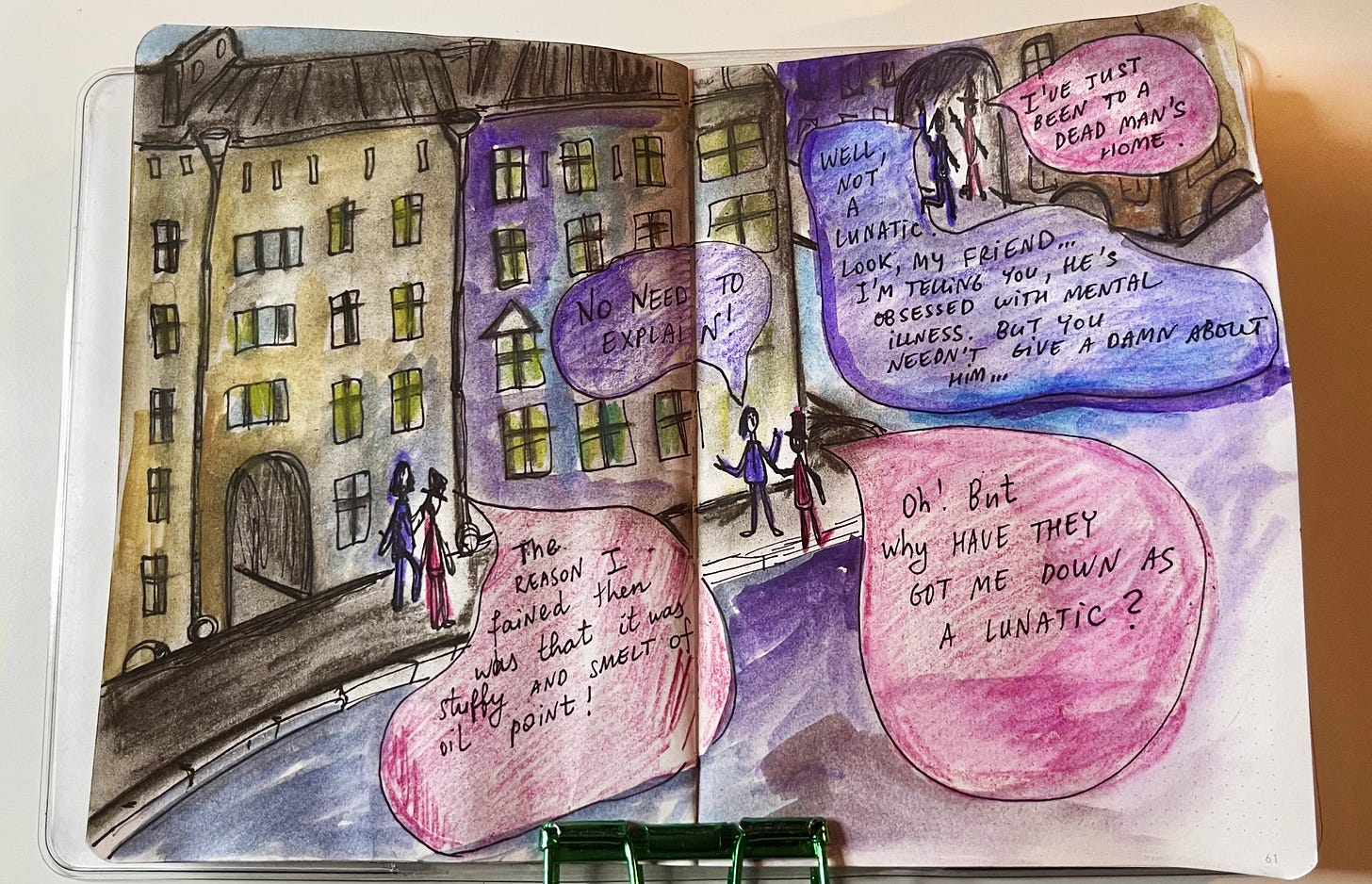

Rodion goes home

He even decides to visit Razumikhin and ask for forgiveness for his behavior. It seems to him that everything has worked out. The two of them walk through the night city and chat like two friends. Rodion now seems unafraid that he will be caught, that they will think he is a murderer. He has logical explanations, alibis for everything. But all this ends instantly as soon as he sees the light in his room. All his confidence disappears in a moment.

Raskolnikov discovers his mother and sister who have arrived in Petersburg. But he is unable not only to rejoice at their presence but even to embrace them — feeling that the chasm between him and the world, formed after the murder, has most deeply separated him from those for whom he, mainly (at least, claiming this when contemplating the crime) committed the bloody deed. But in fact, no, it gives no advantages to his relatives. Unable to bear all this, he even loses consciousness...

What will he say to his mother and sister? This is how the 3rd part of the novel will begin.

How did you like the chapter? And all the second part?

At the end of next week, there will be a post with answers to questions about this part of the novel. You can still write your questions in the chat.

I gotta say Raskolnikov's ever changing mental state is the least interesting thing to me, or maybe the less poignant? How can one call him good or evil when his mind is never set on anything? He himself keeps repeating he doesn't know where his reactions come from, he cannot regulate how he responds to his own emotions and what happens around him. So who's the real Rodion, the one who asks to pray for him or the one who shrugs at God a moment later? The one who kills or the one who gives all his money to widows? Looking for an answer seems pointless. There isn't one. He's obviously not in his right state of mind.

I'm surprised you hated him for bringing Marmeladov home, Dana. He wasn't the only person there, the street and then the house were flooding with people, with police who just wanted to get rid of the problem and let the rich man's carriage pass. Of neighbors who nosed about, laughed, smoked in front of a sick woman. The doctor was useless (do you think an hospital would have been any better? Did they even have ambulances?). I was the most shocked at the priest's uselness. He didn't offer one word of comfort, and even called Katerina Ivanovna's very raw, very understandable reaction a SIN. Nobody in that room saw those three wretched children and thought for one second to help this family or offer comfort, except Rodion, and he's insane. Why is he to blame?

I wonder if Marmeladov killed himself? The carriage driver couldn't tell. It would be the second suicide attempt Raskolnikov witnessed in one evening. Was Marmeladov aiming to find some comfort at last in the presence of God? That speech he gave when we first met him really stood with me. And yet suicide is a sin, and he had the devil's hoof imprinted over his heart (talk about symbolism!) Like I said last week, Dostoevsky's morality baffles me. No, that's not the right word. I understand what he's doing, and I don't like the conclusions he comes to.

Another fantastic chapter…and I certainly never saw this death coming. I was most touched by the final interactions between Sonya and her father. When M. see Sonya’s shame on display in her clothing, he instantly regrets what his actions have done to her…far too late. It’s as if having never seen the attire of her trade, he’s been able to deceive himself into believing she has not sunk to these depths. But just as his realization comes too late to change what Sonya has become, so does his reach for forgiveness. He falls onto the floor, dying before Sonya is able to release him from his guilt.

We have to look at Rodion in the light of this interaction. Does he still have time to be forgiven or is it too late? He is clearly longing for the forgiveness that M. preached about in 1.2 (below). Sonya’s sister promises to pray for him, but is the faith of a child enough?”

“And He will say, ‘Come to me! I have already forgiven thee once.... I have forgiven thee once.... Thy sins which are many are forgiven thee for thou hast loved much....’ And he will forgive my Sonia, He will forgive, I know it... I felt it in my heart when I was with her just now! And He will judge and will forgive all, the good and the evil, the wise and the meek.... And when He has done with all of them, then He will summon us. ‘You too come forth,’ He will say, ‘Come forth ye drunkards, come forth, ye weak ones, come forth, ye children of shame!’ And we shall all come forth, without shame and shall stand before him. And He will say unto us, ‘Ye are swine, made in the Image of the Beast and with his mark; but come ye also!’ And the wise ones and those of understanding will say, ‘Oh Lord, why dost Thou receive these men?’ And He will say, ‘This is why I receive them, oh ye wise, this is why I receive them, oh ye of understanding, that not one of them believed himself to be worthy of this.’ And He will hold out His hands to us and we shall fall down before him... and we shall weep... and we shall understand all things!”