2.6 “Rodia, you’re a clever lad, I grant you, but you’re an idiot!”

Raskolnikov is trying to understand the consequences of the murders he commited. And as we can see, in this chapter he is walking almost the path as on the day of the his crime.

Hello, Dostoevsky enthusiast!

List of articles by chapters you can find here

Reading schedule is here.

The discussion of the novel is completely free for my subscribers. Please subscribe and share the articles and your thoughts in the comments.

This is a very rich chapter in terms of meanings and symbolism. I will only cover the main points. I think you will have questions about other details, so please write your questions - here in the comments or in the Q&A chat for the second part. Depending on how complex and detailed an answer is needed - I will respond either there or there.

“This was the first minute of a strange state of sudden tranquility.”

Rodion finally felt a sense of freedom. After all his encounters in the cramped room, not that he particularly participated in them, I think he really needed to clear his head. For the 4 days while he was delirious, someone was always around, people often visited him, talking "over his bed". How hot it must have been in his room — considering it was a hot July, the room was the size of a closet, and not well-ventilated. Plus, Rodion had a high fever. I think that's why he gave that speech to Razumikhin on the street, so that everyone would leave him alone.

Raskolnikov is trying to understand the consequences of the murders he commited. And as we can see, in this chapter he is walking almost the path as on the day of the his crime. They say in modern detective stories that the criminal always returns to the scene of the crime. I don't know if this is true in reality. But we have our own kind of detective story here.

Let's follow Rodion's route

In this chapter, Dostoevsky also has some inaccuracies with the real map of the city; he sometimes confuses turns and distances. But he didn't aim to reflect the real St. Petersburg; he rather used it as a canvas. The houses do stand at their correct addresses, but Rodion doesn't walk as if in the real city, rather a bit as if in a dream - he goes in the wrong direction, but arrives where he needs to.

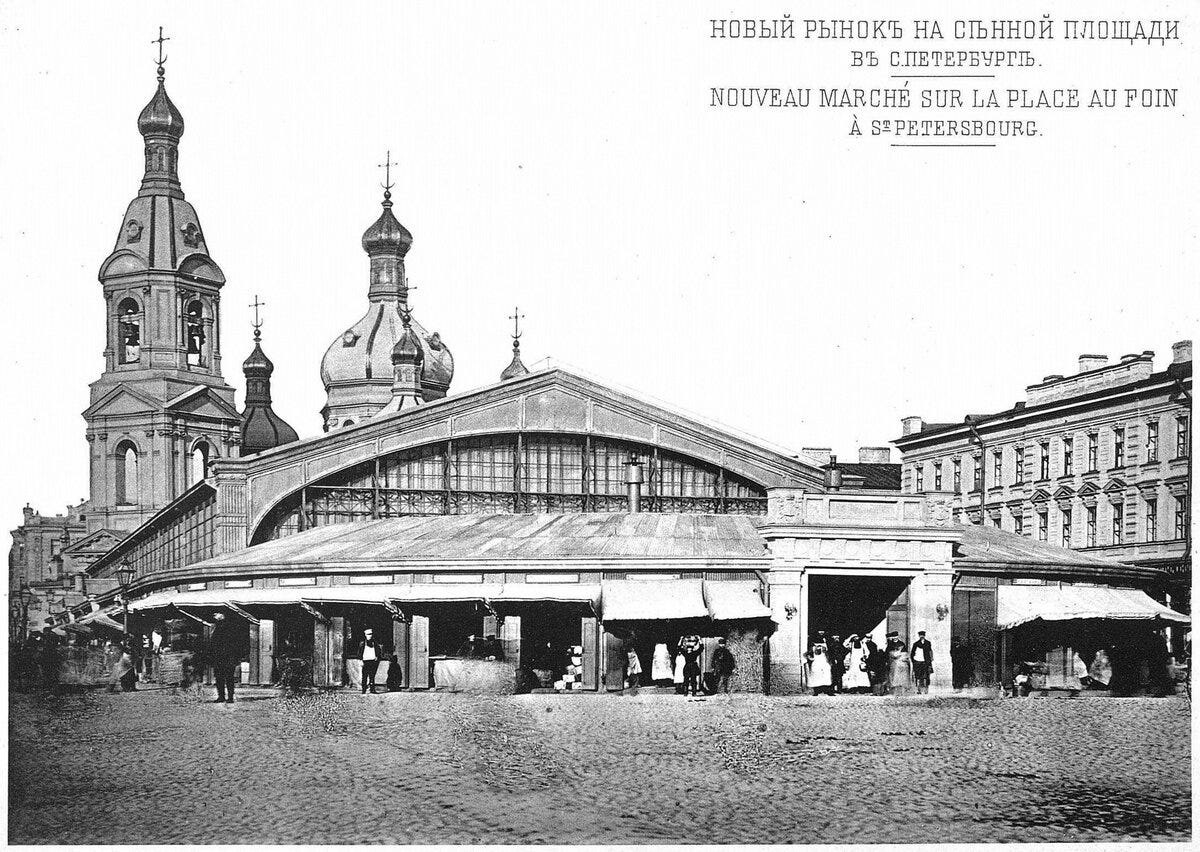

The seedy areas of Haymarket (Sennaya) Square (2 — on the map)

“Yes, it’s a tavern, and they’ve got billiards; and you’ll find princesses there too… Heigh-ho!”*

At the beginning, Raskolnikov stops at Haymarket Square, at the corner of Konnaya Lane. This is where one of the seediest places of Haymarket Square was located, the so-called "Malinnik" (literary Raspberry bush, figuratively, this was used to refer to places where there were many young girls). Much is known about this house from Krestovsky's book about the slums of 19th century Petersburg. They even interviewed one of the prostitutes there, which could be interesting, but we could make a separate article about her. Here's what they wrote about the "Malinnik" of that time.

"The ground floor of this house is occupied by a small shop, two warehouses, and, of course, a tavern. The middle floor of the facade wing is fully occupied by an inn. The upper floor above the inn and the three remaining courtyard wings - all of this, divided into fourteen apartments, is occupied by thirteen dens of the most gloomy, horrifying debauchery. And each of these dens invariably contains several more corner cubicles, separated from each other by thin, wooden partitions. A miserable bed or two boards placed on two log blocks and covered with dirty rags constitute all the furniture of these cubicles, each of which occupies no more than two or two and a half arshins of space (1.4-1.7 meters or 4.6-5.8 feet). Here, in these dens and wooden cells, nest from eighty to a hundred of the most wretched, outcast creatures, given over to murderous depravity."

The price for these women's services did not exceed 50 kopecks. On holidays, a prostitute from the "Malinnik" often served up to 50 men. The girls in such establishments dressed not only poorly, but also indecently primitively. Sometimes their clothing consisted of nothing more than a dirty towel wrapped around their hips.

At this same intersection, Rodion learned that Lizaveta was not supposed to be at home on that fateful evening. And this was the final argument 'for' the crime at that time.

What do you think now, if he hadn't met Lizaveta then and hadn't learned that she wouldn't be home, would he still have gone through with the crime?

Thoughts on the way to the Crystal Palace

After seeing the poorest houses of Petersburg, full of despair, Rodion once again felt a thirst for life.

“Where was it,’ wondered Raskolnikov as he walked on, ‘where was it that I read about someone who was condemned to death, and an hour before his execution he said, or thought, that if he was made to live on some great height, on a cliff, on a platform so narrow that there was just room for his two feet, with the abyss all around, the ocean below him, everlasting darkness, everlasting solitude, and everlasting storms—and he had to stay up there, standing on a foot of ground, for all his life, a thousand years, for all eternity—it would be better to live like that than die at once!* Just to live, live, and live! No matter how one lives—just to be alive!… How true that is! Lord, how true! Humankind are villains! And anyone who calls them villains for being like that is a villain himself,’ he added after a minute.”

This recollection of Raskolnikov partly stems from Victor Hugo's novel "The Hunchback of Notre-Dame," which was published in the Dostoevsky brothers' journal "Time" in 1862. It presumably refers to the episode of Archdeacon Claude's death, his feelings a few minutes before falling from the height of the cathedral. It also relates to another Hugo novel, "The Last Day of a Condemned Man," which was already mentioned in chapter 1.6, when Rodion described how he felt while going to the old woman's place.

But here's the strange thing — being, as usual, focused on himself, Raskolnikov doesn't think at that moment that all other people are consumed by the same desire to live, and therefore — what a terrible sin it is to willfully deprive them of life; moreover, one can't help but notice here Raskolnikov's inclination towards a romantic perception of the universe and himself in it — a hero on a cliff, with an eternal storm all around.

Now he would need to combine this indestructible thirst for life with what helps a person to live, promotes life — and what, on the contrary, leads him to death — and then, possibly, understand the whole foundation of the universe.

But that's still far off; for this, mental work alone is not enough — the entire inner being of a person must change. For now, Raskolnikov draws only this conclusion: «Humankind are villains! And anyone who calls them villains for being like that is a villain himself»

“Aha! The “Crystal Palace”!” (3 — on map)

Dostoevsky refers to a real hotel by this name, which was located at the corner of Voznesensky Prospect and Sadovaya Street. However, he transforms it into a dirty tavern. This is likely done to show the contrast between the pompous name and the squalid content. The Crystal Palace was the name given to the magnificent glass and metal building constructed by architect Joseph Paxton in Hyde Park, London, for the Great Exhibition of 1851.

The Crystal Palace made a strong, but not quite usual, impression on Dostoevsky during the writer's visit to London in 1862: "You feel the terrible force that has united all these countless people, who have come from all over the world, into a single flock; you recognize the gigantic thought; you feel that something has already been achieved here, that there is a victory, a triumph. You even begin to fear something. No matter how independent you are, you somehow become frightened. Is this, indeed, the achieved ideal? <...> Will we have to accept this, indeed, as the complete truth and fall silent forever? <...> you feel that something final has been accomplished here, has been accomplished and completed. This is some kind of biblical picture, something about Babylon, some prophecy from the Apocalypse, visibly coming true. You feel that much eternal spiritual resistance and denial is needed in order not to succumb, not to submit to the impression, not to bow down to the fact and not to deify Bael."

(Bael is a powerful demon, his name translates from the common Semitic as "master", "lord". Human sacrifices were offered to him. In the infernal hierarchy, he is the commander-in-chief of the hellish armies)

The name "Crystal Palace" was also used to denote happy places of human habitation in a future just social order by various "progressive" thinkers and revolutionary utopian activists.

And in this Crystal Palace, newspapers were served to visitors - and Raskolnikov wants to read what they write about the murder of the old woman and Lizaveta. Catching him in this process, a clerk from the police office, Zametov, approaches him - and Raskolnikov once again returns to aggressive confrontation with the world: he begins to mock Zametov ("Not at all, my little sparrow!"), and then starts a psychological duel with him, as if provoking the clerk to suspect him of murder. The conversation turns to the topic of various kinds of crimes, and Raskolnikov, in the spirit of his favorite idea, again states that "ordinary" people usually commit crimes very stupidly and therefore get caught, but the chosen, extraordinary ones (he, Raskolnikov) - smartly, cold-bloodedly take into account psychological subtleties. He seems to forget at that moment what an absolute unbridled chaos and mess his crime was, an the fear that was eating away at him ever since.

Furthermore, Raskolnikov expresses a very significant thought, clearly conveying not only his current state but also his general view of the world up to this point: speaking about - as we would say nowadays - criminal organizations or gangs, in this case counterfeiters (I wrote about this case in the previous article for 2.4-2.5, where one of the main criminals is a relative of Dostoevsky himself), and the fact that if anyone from the whole group "blabs while drunk, everything goes to dust!", he declares.

“What about the rest of their lives? Each one of them depending on all the others for the rest of their lives! Better hang yourself right away!”

Raskolnikov has yet to understand that it's impossible to live any other way than to depend on and be connected by the strongest threads to all people around - both near and far. He hatefully asks Razumikhin, who has rushed after him, to stop his "benefactions" (he, the "benefactor" of humanity, cannot stand others' benefactions). And he again falls into melancholy, again having thoughts about wanting to die. Razumikhin even fears that he might drown himself.

Here again - before the Crystal Palace he was for a moment overtaken by a desire to live, no matter the conditions, but then again - despair and a desire to end it all.

Why do you think his thoughts jump around like this?

Voznesensky (Ascension) Bridge (4 — on the map)

Stepping onto the bridge and leaning on the railing, feeling as if all his vital energy was draining from him, he gazed into the water "attentively". But from falling off the bridge, whether consciously or involuntarily, he is saved by the action of a drunk woman who throws herself into the water from the bridge next to him.

Perhaps this is again a metaphor, that this is Raskolnikov's own soul, drunk with sin, as if fulfilling its owner's subconscious urge for suicide (which will later take hold of him with full force), committing this wild act. This woman, as it turns out later, is called Afrosinyushka (i.e. Efrosinya - meaning "joy" in Greek). Dostoevsky constantly reminds us of the contrast between what should have been - and what, due to human sins, actually is, but her appearance does not correspond to her name at all. She is a woman with a yellow, elongated, haggard face and reddish, sunken eyes. There is no joy in her.

But they won't let her die. She was fished out and laid on the granite slabs of the embankment. She regained consciousness soon. This scene of suicide on the canals is not uncommon. Newspapers of that time frequently wrote about such cases. It was a mundane reality of life in that area of the city.

«What about the rest of their lives? Each one of them depending on all the others for the rest of their lives! Better hang yourself right away!”

Remember?

Life immediately shows Raskolnikov — "you're a clever lad, but you're an idiot," as Razumikhin tells him — that hanging oneself is actually most likely possible when there is no dependence on and help from others.

The house of the old pawnbroker woman, the crime scene (number 5 on the map)

But this painfully obvious example is also not yet understood by Raskolnikov. In complete apathy, almost mechanically, he again goes to "turn himself in" at the police station — more out of despair and loss of all strength for further existence than anything rational. But his feet lead him not to the station at all, but "to the scene of the crime".

Does the criminal really always return to the scene of the crime?

Driven by an "irresistible and inexplicable desire," Raskolnikov obeys and enters the apartment where he committed the murder. He very much dislikes that everything has changed here; on the wall in the bedroom, he notes the place where the icon case stood then. After looking at the workers remodeling the apartment, he begins to ring the doorbell, just as the people who came to the old woman did then, this time himself, as if wanting to experience again those sensations when he froze at its ringing on the other side of the door.

And then he begins to ask the workers about the blood, of which there was a whole puddle there. After that, he tries to provoke the workers and the janitor into taking him to the police.

He keeps wanting someone else to resolve his fate — he wants to be caught, after all, he could have turned himself in many times already.

Eventually, he is thrown out onto the street, where he continues to ponder whether to go to the police or not. Rodion, «stopping in the middle of the roadway at a crossroads and looking around as if expecting a decision from someone else. But no reply came; all was as silent and dead as the stones he trod on, dead for him, for him alone».

It seems the darkness around Raskolnikov and his loneliness in the world have reached their extreme limit. He is alone in the middle of the street, silence all around.

Suddenly, far away, about two hundred steps from him, at the end of the street, in the gathering darkness, he distinguished a crowd, voices, shouts... Among the crowd stood some kind of carriage... A small light flickered in the middle of the street... Raskolnikov walked towards this light, somehow firmly knowing that everything would end for him now. And indeed, at this moment that former self of his ends and a new story begins…

How did you like the chapter?

The 7th chapter is the last chapter of the second part of the book!

As we're discussing Part 2, Chapter 6, I was reminded of a scene in Part 1, Chapter 6, where students are talking about crimes and murderm in a pub. They create theories on how things should be done. What do you think about this parallel? Perhaps the protagonist wants to return to that world, to that time before the murder, and behave as the students did?

I'm struggling a bit here. I've only ever read another Dostoevsky book before this, Notes from the Underground, I disliked it so much I wanted to throw it across my room. This chapter reminds me of Notes the most so far. Raskolnikov's mood swings seem narratively cheap and morally exhausting at this point, as do the various portraits of human misery and debauchery. I see that Dostoevsky was reacting to the rational egoism of his time, but his conclusions are soooo frustrating.