2.4 & 2.5 «He’s got nothing to say about anything, except this one thing that drives him wild: that murder…»

What are the conversations around Raskolnikov's bed while he looks at the ceiling and then at the wallpaper? Of course, about murders and crimes...

Hello, Dostoevsky enthusiast!

List of articles by chapters you can find here

Reading schedule is here.

The discussion of the novel is completely free for my subscribers. Please subscribe and share the articles and your thoughts in the comments.

Today we will talk about two chapters at once, 2.4 and 2.5 — in fact, this is one scene, divided by Luzhin's arrival. That is why it is interesting to consider them together.

What are the conversations around Raskolnikov's bed while he looks at the ceiling and then at the wallpaper? Of course, about murders and crimes... Also, find out which real criminal (from a high-profile case!) was a relative of Dostoevsky.

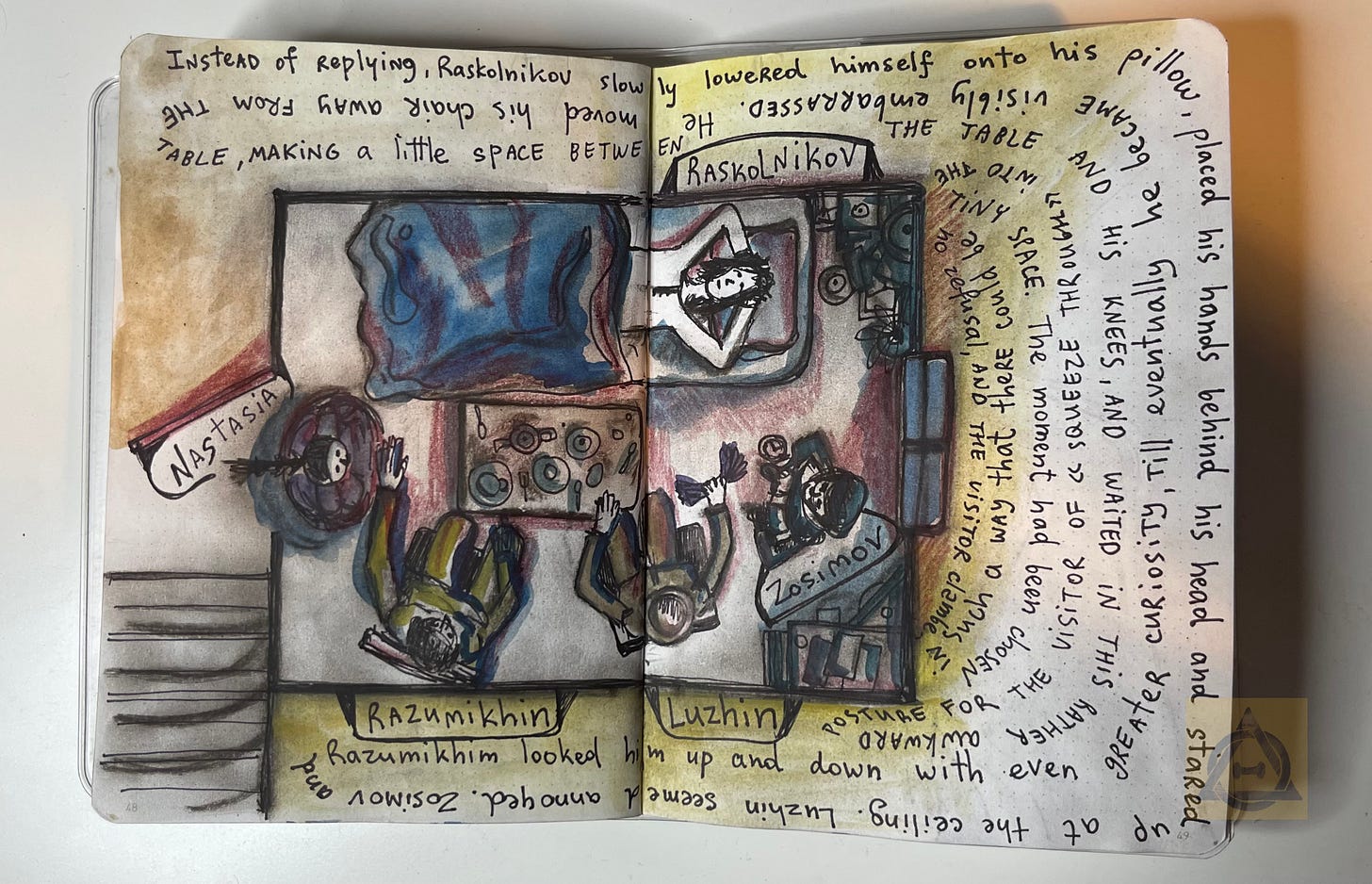

In 2.4, only Razumikhin and Zosimov (and Nastasya, but she is also silent) are in the room with Raskolnikov.

Discussion of the crime by armchair critics

— “That Lizaveta, she was killed too!’ Nastasia burst out, addressing Raskolnikov. She had stayed in the room the whole time, lurking by the door and listening.

—‘Lizaveta?’ mumbled Raskolnikov, almost inaudibly.

—‘Yes, Lizaveta, who sold old clothes, didn’t you know her? She used to visit downstairs here. She mended your shirt, too.’

Razumikhin and Dr. Zosimov discuss the murders. The interesting thing here is that Raskolnikov seems to have forgotten that he killed not only the old woman. When they mention Lizaveta, he seems to try to remember and piece something together. It is still a shock for him. I lean towards the idea that it was the murder of Lizaveta that was the breaking point for him. He had been preparing himself for the crime against the old woman for a month, and most likely everything would have been different if Lizaveta had not returned home then. But this is only a hypothesis; something would have definitely changed. He had his own reasons for the old woman; he had defined for himself why he would kill, and, as we remember, he even reflected that it was not a crime at all. He justified it in his mind, convinced himself. He did not want to kill Lizaveta and planned the murder so that she wouldn’t be home. But fate intervened again.

After this, he seems to lose interest in the people beside him and turns to the wall, thinking about Lizaveta, perhaps.

“Raskolnikov turned to the wall and contemplated the dirty yellow wallpaper with little white flowers; he picked out one odd-shaped white flower with some brown lines on it, and began examining it, counting the petals, looking at the scallopings on each petal and counting the little lines. His hands and feet felt numb, as if they didn’t belong to him, but he made no attempt to move—he just went on looking at the flower.”

In the novel, plants, and nature have their own symbolism. If we recall how Raskolnikov changed when he left the city and walked through the green islands in the north, he almost got rid of the thought of committing a crime. He enjoyed the flowers, the open air. And here in this cramped, dirty room, Raskolnikov finds his peace — in this white flower on the wallpaper. It is a tiny point of hope that can flourish or wither. Raskolnikov needs to understand how to take care of this flower.

In the reflections of Razumikhin and Zosimov, several details are interesting:

“Because everything comes together so perfectly… and fits in so well… just like in a play.”

In general, as Zosimov remarked, it’s all like a play script. This is a trick of Dostoevsky, which can be called a "false bottom." We know that we are reading fiction, yet we accept it as fact for ourselves and reason logically within the framework of the novel, applying everything to reality. And the characters remind us that this is all fiction, the author's invention.

And indeed, Dostoevsky comes up with this "false" version of the murder disclosure. The police have "false" suspects and evidence. There is the painter, who worked on the second floor, and in this apartment, Raskolnikov hid on his way down to avoid being caught.

The Arrival of Pyotr Petrovich Luzhin

And now there are already 5 people in Rodion's small room. It's not clear at all how they fit in there, to be honest.

“His face, which he had turned away from the curious flower on the wallpaper, was unusually pale and bore an expression of great suffering, as though he had just emerged from an excruciating operation or been delivered from torture.”

Rodion turns away from the flower, which seemed to have a calming effect on him. And now he expresses suffering entirely. I think he has started to torment himself with thoughts of Lizaveta and the old woman again. But Dostoevsky in these chapters does not allow us to read Rodion's thoughts, we can only guess what he’s going through at this point.

It seems like Rodion does not immediately recognize Luzhin. For some reason, it seems to me that he is pretending and waiting until the last moment. Yes, a lot had happened to him after reading his mother's letter, but he could not forget it — because of it, he ran all the way to the north of the city in a rage. His name and surname must have been imprinted in his mind. Raskolnikov’s pose — hands behind his head — suggests some kind of demonstration in front of Luzhin. I think he immediately understood who it was.

Luzhin's Theories

“The result would be that I would tear my cloak in two and share it with my neighbour, and each of us would be left half-naked, for as the Russian proverb says, “chase several hares at once and you’ll catch none”

Luzhin reinterprets the parable of the torn coat from the commandment of John the Baptist (Luke 3: 10-11).

10-11. “What should we do then?” — the crowd asked. John answered: “Anyone who has two shirts should share with the one who has none, and anyone who has food should do the same.”

Both Raskolnikov and Luzhin are "theorists." Luzhin's views resemble "rational egoism," but he articulates them in an absurdly down-to-earth manner—much like he tries to ingratiate himself with his neighbor Lebezyatnikov (this is the character who beat Marmeladov's wife and expelled Sonia because she did not want to sleep with him, although before that he gave her a contemporary and radical book "Physiology" to read — see more in the article for chapter 1.2) , a grotesque "new man" who goes against the biblical commandments.

“But science tells us: “Love yourself above all, for everything on earth is founded on self-interest.” If you love yourself alone, you will manage your concerns properly, and your cloak will remain whole. And economic truth adds that the better that private concerns are managed in our society—the more whole cloaks there are, as it were—the firmer society’s foundations become, and the more the common good is promoted.”

The point of view presented by Luzhin seems like a parody. This is how he defines the highest justice and the way to progress. He’s not talking of personal responsibility, though, merely of personal gain which in his mind will elevate the whole society and therefore help the less fortunate too.

These ideas were expressed in Pisarev's article "Historical Ideas of Auguste Comte", and Dostoevsky made them a part of Luzhin’s philosophy. In the 1860s, these ideas were very widespread, but also radical at the same time.

The "moral" with which Luzhin concludes: "If you love yourself alone, you will manage your concerns properly, and your cloak will remain whole". Through Luzhin, Dostoevsky contrasts Christian morality with the popular contemporary morality (of that time), which tries to transform it.

That is why the saying "Chase two rabbits — catch none" is also mentioned here. This may refer to the fact that it is impossible to simultaneously live by Christian commandments and try to adhere to new economic principles. However, society tries to combine both.

We know what Dostoevsky himself chose. But what do his characters choose?

It is also worth noting the callback from the torn shirt to the shirt mentioned before. A ripped shirt Lizaveta mended for Raskolnikov once. And that is displayed against the backdrop of Luzhin discussing the idea of committing selfish acts, justifying them as a way to the greater good.

What crime of ticket forgery are they discussing?

In the pages of "Crime and Punishment," this matter is mentioned by Luzhin. During his first meeting with Raskolnikov, he keenly joins the discussion of the murder of the old pawnbroker, contemplating the global changes in society that push not only representatives of the lower classes but also educated people to break the law.

“So we hear of a former student robbing the mail on the highway; or of people in the topmost ranks of society forging banknotes; or of a whole gang of forgers in Moscow caught counterfeiting the latest issue of lottery tickets, and one of the ringleaders was a lecturer in world history; or of one of our embassy secretaries murdered abroad for some mysterious financial reason…”

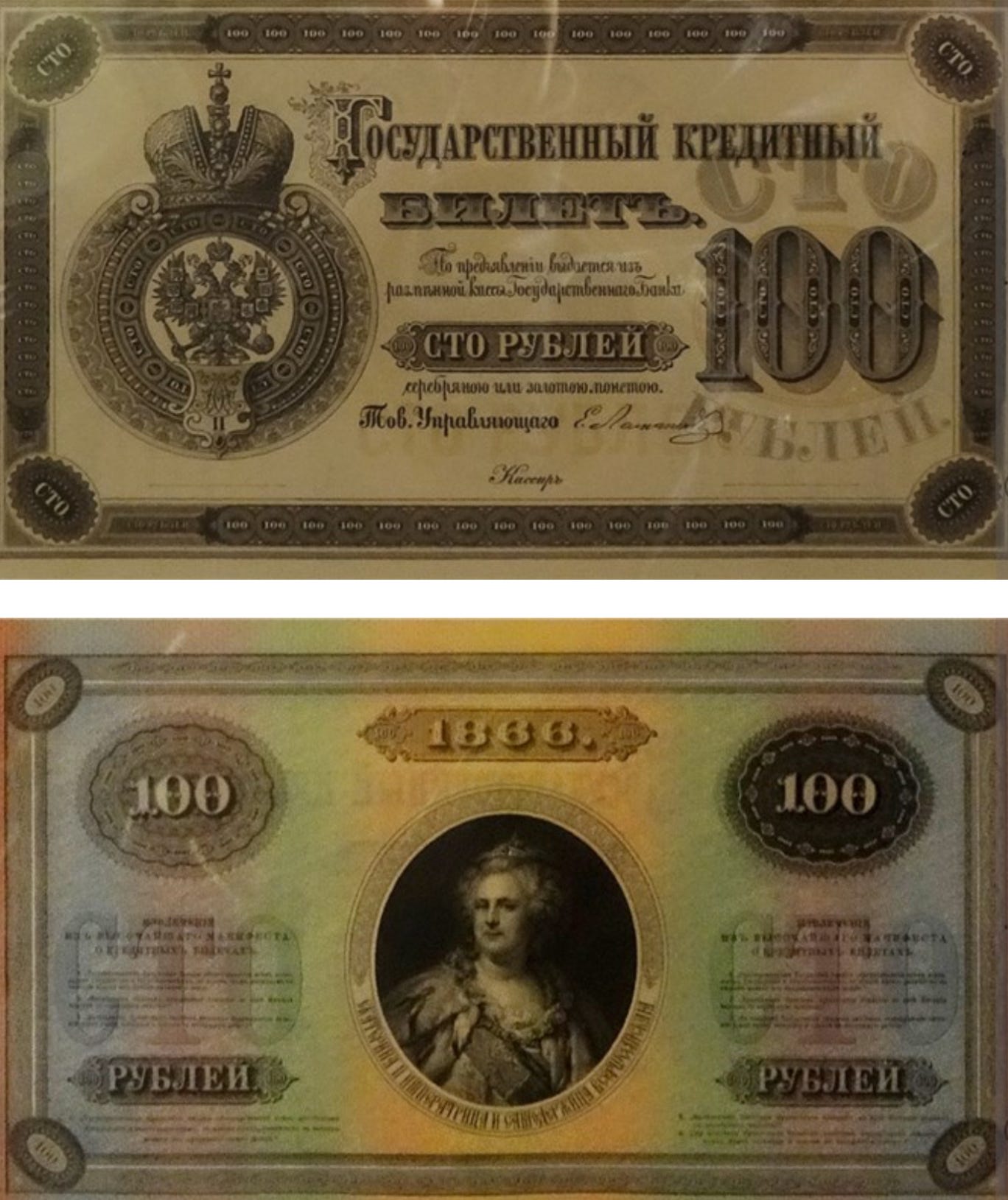

At the turn of 1865-1866, "Moscow News" published materials of a court case about the forgery of internal loan tickets. These securities appeared a year earlier and became popular among the population as they offered an unconventional interest payment on the bonds. Every citizen could purchase a ticket with a nominal value of 100 rubles with a promised 5% annual interest. The term of the paper was 60 years.

Tickets with a face value of 100 rubles were also called "rainbow tickets" because they were multicolored on the front side.

At the same time, the State Bank held annual drawings similar to a regular lottery. Two drums were loaded with paper tubes containing combinations of numbers. Two slips were taken from the first drum to determine the series. One slip was taken from the second drum to determine the number of the winning ticket. The winner received 200 thousand rubles. The holder of the second lucky ticket received 75 thousand rubles. A total of 300 prizes of various monetary values, totaling 600 thousand rubles, were given out in a single drawing. Soon, due to the growing popularity of the lottery, it was officially allowed to sell tickets for 105 and 107 rubles; on the stock exchange, one bond could be purchased for 150 rubles.

Fraudsters also appeared, seeking to profit from the popularity of securities. They forged them and exchanged them with wealthy citizens for real money or sent proxies to exchange the securities in private offices.

Crime

A young man named Vinogradov, who introduced himself as a student, came to one of the Moscow offices. He offered to redeem a state certificate with a winning loan of 5000 rubles. While counting the received money, he got confused and aroused suspicion. When the student was arrested, he testified: it turned out that Vinogradov had been hired for 100 rubles, and through a chain of intermediaries, the investigation led to the authors of the criminal scheme. One of the evil geniuses was Alexander Neofitov, a professor of world history at the Practical Academy of Commercial Sciences. Neofitov explained his involvement in the criminal plot by his desire to quickly earn money and help his mother:

"Seeing the difficult situation of his affairs and his mother's affairs, wishing to strengthen his position as much as possible, and at the same time observing people who easily enrich themselves by illegal means without any responsibility, he came up with the idea to take advantage of the ease of illegal acquisition and secure himself and his mother's family."

Interestingly, this Alexander Neofitov was a relative of Dostoevsky on his mother's side. Neofitov's mother was the first cousin of the writer's uncle, A. A. Kumanin (the husband of Dostoevsky's mother's older sister), and the writer could not help but be painfully affected by all the details of his case. Like Dostoevsky himself, A. T. Neofitov was an heir of A. F. Kumanina, from whom he borrowed 15,000 rubles against the security of three forged lottery loan tickets. These events personally affected the writer.

Neofitov confessed to everything, but, as the newspapers wrote, "not to the investigator, but to his own conscience, as a criminal he had every opportunity to further deny and remove the accusation from himself... <...> The moment of Neofitov's confession was a sacred moment of the awakening of his honest, uncorrupted soul, which had been carried away by temptation. He brought his sincere repentance through all the investigations and now presents it to the court as a purifying sacrifice," wrote "Moscow News" (1865, No. 3).

Moreover, neither the investigators, nor the newspapers, nor Dostoevsky could have guessed that the seemingly repentant Neofitov would continue his criminal activities even in prison. In 1877, he would become one of the figures in the case of the “Jacks of Hearts Club” (Klub chervonnykh valetov) as a member of a group of counterfeiters. Together with other inmates, Neofitov established a mechanism for counterfeiting banknotes and a system for delivering them outside the prison. It is believed that this was the strongest Organized Crime Group of the Russian Empire.

Dostoevsky's relatives were excellent — they provided interesting material for his books!

There are more and more suspicions that something is wrong with Rodion.

“But did you notice that Rodia doesn’t care about anything, he’s got nothing to say about anything, except this one thing that drives him wild: that murder…”

In general, their suspicions, based on absolutely nothing except Rodion's condition, will move the plot of the novel forward. And so Rodion finally drives everyone out of the room. And he is left alone.

How did you like these chapters and the discussions around Rodion? What would you like to note?

What do you think Rodion will do next?

The sixth chapter is long and rich (18 pages) — so plan your reading time accordingly.

I'm curious to see what "team" Razumikhin and Zosimov end up on, especially as things start to unfold. It seems like they're taking pity on Raskolnikov with some level of caring, but I don't seem them as potential friends or defenders. As far as recognizing Luzhin or not, I took it as more of he's living in two "worlds" and in the context of "fugitive world" anyone from "family drama world" might seem out of place at first. PS I love the drawing of everyone in the room--it reminds me of the Marx Brothers scene where people kept piling into a ship's stateroom ( https://youtu.be/rCyR113uZ_o )

Chapter five is especially interesting. All the characters are so vivid in my mind, especially Razumikhin and Luzhin, who is just as snobbish and selfish as Rodion's mom suggested. His rants about biblical cloaks sounded like trickle down economics according to Ayn Rand, it was weirdly satisfying when Raskolnikov told him to f*** off. In a sense our Rodion is right, you can't expect others to be nice to you if you won't be nice to them, selfishness is a two-way street. He's once again villain and victim, he's fallen from the upper classes and is now wallowing in hell, a strange champions to the misfits that Luzhin is helping create. Razumikhin is shocked by his rudeness because he still plays by the rules. There are no rules left for Raskolnikov.

I can see that Razumikhin has not bad intentions, but I still don't like him, ahahah. As the good doctor said, he's a nosy busybody. He enjoys being right and proving how smart he is, I think.

Thank you Dana for pointing out the "false bottom"! It's like we accept all the people fitting in that small room because we low-key know that the room is actually a stage and the 4th wall is down to let us look in.