2.2 “You know what? You’re raving!”

So we have turmoil and chaos after the crime. Let me remind you that it is still the day after the murder. Raskolnikov cannot come to his senses and is still trying to comprehend what happened.

Hello, Dostoevsky enthusiast!

List of articles by chapters you can find here

Reading schedule is here.

The discussion of the novel is completely free for my subscribers. Please subscribe and share the articles and your thoughts in the comments.

A small survey. It will be interesting to understand if your attitude towards the novel changes as you read.

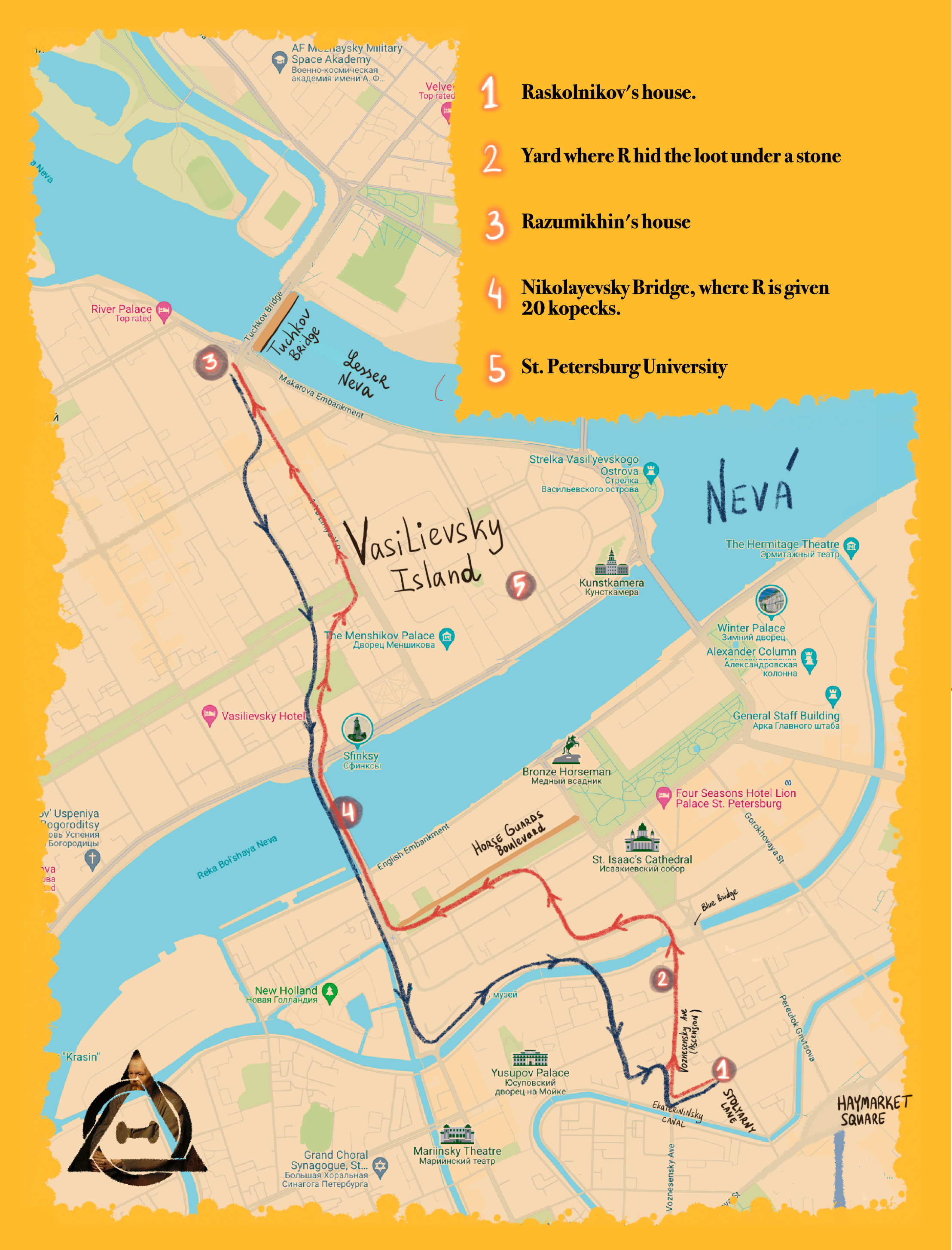

In this chapter, Rodion once again walks a lot and far through the city. His route is reminiscent of the one from chapters 4-5, when he ran out agitated after reading his mother's letter. But let's go in order.

After visiting the police office, Raskolnikov developed a new obsessive thought that they were definitely onto him, watching him, and would come with a search warrant. He urgently needs to get rid of the evidence — the loot.

We learn for the first time what exactly Raskolnikov took from the old woman, and he took very little, just 8 items of uncertain value and a wallet. Rodion didn't even take or remember his own items that he had pawned to the old woman — his father's watch and a ring. And these things were dear to him once.

“There were eight items in all: two little boxes containing earrings or something of the sort—he didn’t look properly; and four small leather jewel-cases. One chain, simply wrapped in newspaper. And something else, also in newspaper—probably a medal…”

Yard (2 on the map to the chapter)

Rodion thinks for a long time about where to hide the loot. At first, he wants to throw everything into the canal, but then he decides to take it as far away from home as possible. However, he comes across an entrance to a yard. And there's no one there.

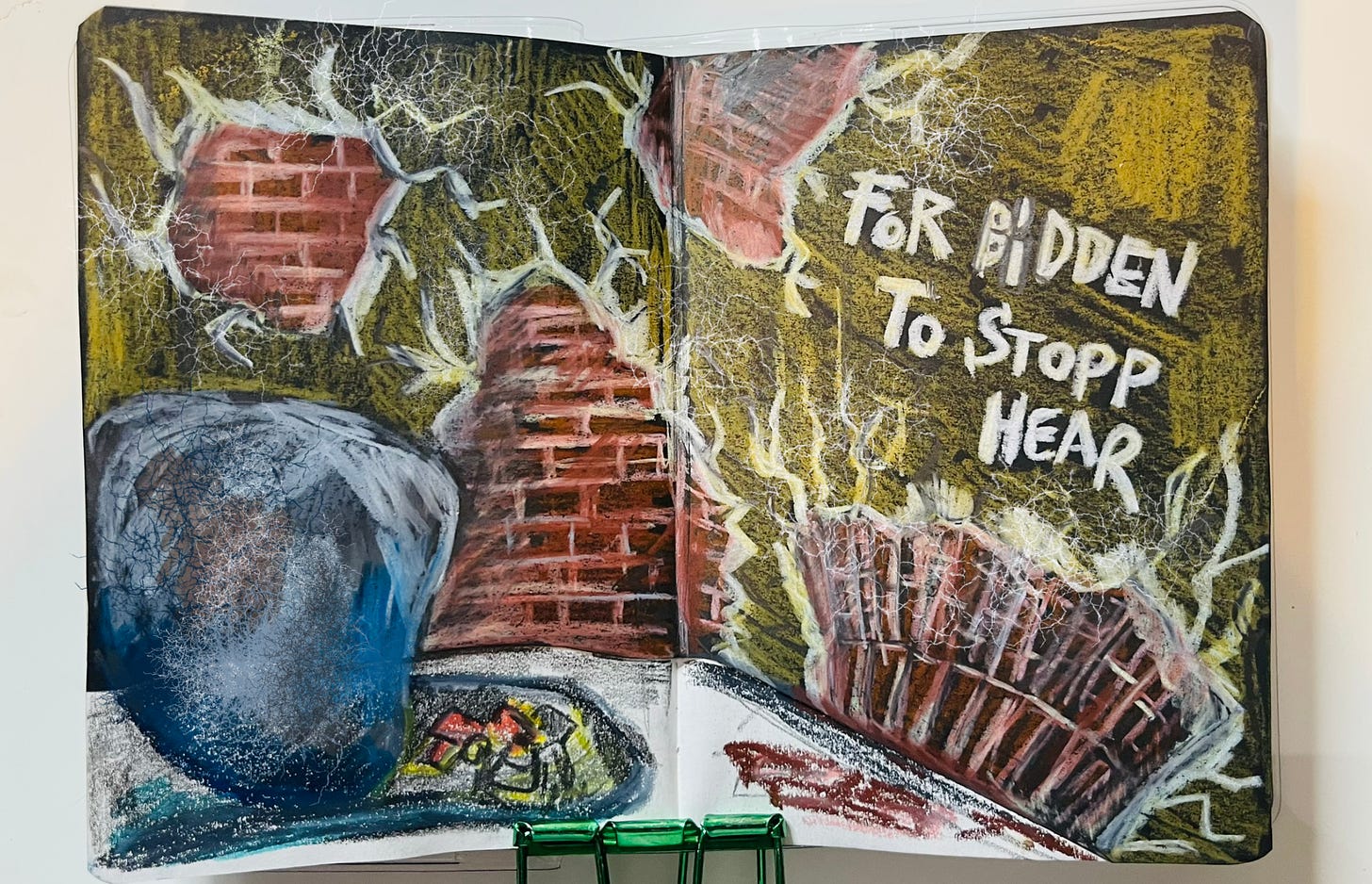

“Something else happened instead. Coming out of V—— Prospekt onto a square, he suddenly noticed to his left a passage leading to a yard entirely surrounded by blank walls.”

We are talking about Voznesensky Avenue and Mariinsky Square in front of the Blue Bridge over the Moika River.

Anna Dostoevskaya, his wife, wrote:

"Fyodor Mikhailovich, in the first weeks of our married life, while walking with me, took me to the courtyard of a house and showed me the stone under which his Raskolnikov hid the items stolen from the old woman. This courtyard was located on Voznesensky Avenue, the second from Maximilianovsky Lane (now Pirogov); a huge house has been built on its site, where the editorial office of the German newspaper ('St.-Petersburger Herold') is now located. When I asked him, why did you wander into this deserted courtyard? Fyodor Mikhailovich replied: 'For the same reason that passersby go into secluded places'."

That is, to relieve himself.

Thus, it becomes definitely clear what Dostoevsky meant with his poorly spelled chalk-written message on the wall. It was a warning not to stop there to go to the toilet. For some reason, in some translations, it was decided that carts couldn't be stopped there. It must be understood that this was a smelly corner, and most likely the stone was also dirty. And Raskolnikov decides to lift it and hide things there. It seems to him that this — the dirtiest place can make him unnoticed, save him, he wants to merge with the stench of the city, become invisible. And immediately he feels relief.

After this, he goes north of the city again, as he did the day before yesterday. He walks past that bench where he saw the drunken girl, goes through Vasilievsky Island, and reaches Tuchkov Bridge. The last time he crossed it and went to the islands, and this time he decides to visit Razumikhin.

At Razumikhin's (3 — on the map)

Razumihin Dmitry Prokofyevich (son of Prokofy). Razumikhin — the surname is derived from the word "razum" (reason).

Rodion already mentioned his friend from university. He said that he is a friendly, optimistic person. It seems that he is the opposite of the depressive Rodion. Despite not being in contact for 4 months, Razumikhin is immediately ready to help Rodion with work. We see that he lives in the same poverty as Rodion. However, while Rodion has started destructive activities and thoughts of murder due to poverty, Razumikhin seems to be brimming with creative energy. He translates a lot of work from German and French. And he even immediately gives Rodion a job and an advance of 3 rubles. In fact, this is quite a bit of money — for the pawned watch he received 1 ruble 15 kopecks.

What do you think of Razumikhin, is he a good person and the opposite of Rodion?

And what do you think about the reason for the visit to Razumihin? He just hid the stolen goods, and the money, and came to his friend asking for work. Is he securing an alibi?

Woman question

“Take these two-and-a-half sheets of German text—if you ask me it’s the stupidest sort of humbug, I mean it’s all about whether a woman is a human being or not. And of course it proves triumphantly that she’s human.”

Dostoevsky ironically paraphrases one of Yeliseyev's feuilletons from the magazine "Sovremennik".

"Are peasants, at least Russian peasants, human?", the author then writes: "Now we move on to the question of women. Are women human? - This question is much more difficult or, more precisely, more delicate to resolve than the question about men. There are the most extreme opinions regarding women. Some say they are incomparably lower than men, others that they are infinitely higher." Examining the attitude towards women in ancient society, the East, etc., from the perspective of contemporary ideas of women's emancipation, the feuilletonist concludes his review by stating that women are beings "much higher than men."

The topic of women's emancipation in the 1860s was very acute. It was precisely at this time that the serfs were liberated, and along with this, the question of women’s rights began to appear. From this point on they could receive education in special Women's Institutes. Of course, they were mainly taught how to be good wives, but the education also included other topics, expanding the knowledge of the world, art, foreign languages, and religion.

And it should not be forgotten that the question "Is a woman a human?" is a significant element in the artistic structure of the novel, resonating with Marmeladov's words about his daughter Sonia: "Behold the human!" obviously quoting Pilate’s words about Jesus, showing the kinship with this man through the suffering he undergoes.

This question is not so much about the differences between men and women and their rights, but about who is a human being in general, and what it means to be human. Rodion also begins to worry about this question concerning himself - can he call himself a Human?

On Nikolaevsky Bridge (4 — on the map)

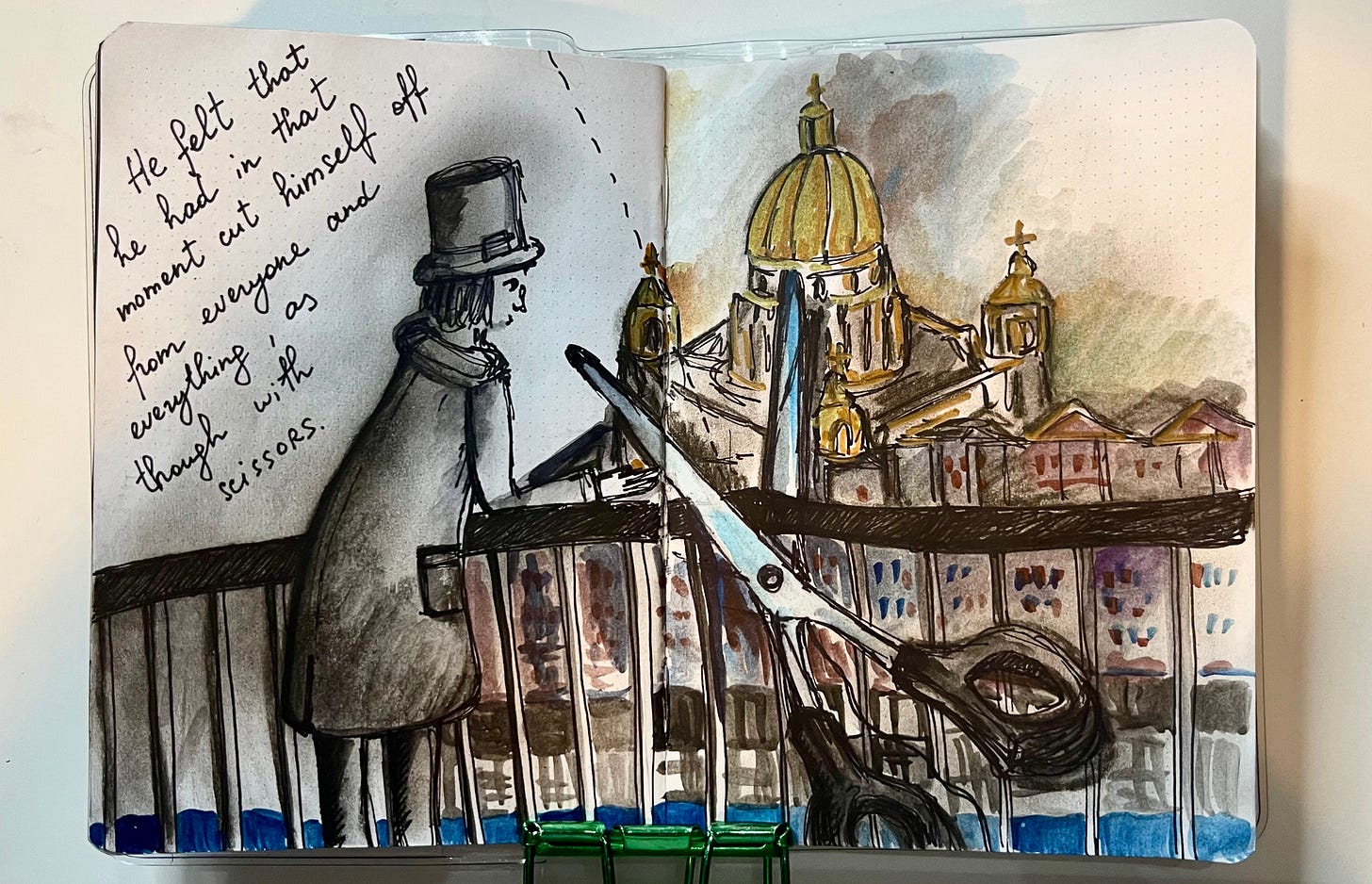

He stopped on the bridge and began to look at the panorama of the city. Before that, he was hit on the back with a whip. This is most likely a reference to Pushkin's poem "The Bronze Horseman," since the monument can be clearly seen from the bridge. If so, then the theme of the "little man" is raised here, and that this man is simply insignificant before to the power and authority.

Raskolnikov indeed looks insignificant against the majestic backdrop of St. Petersburg — after all, he stands against the background of the Winter Palace, the Imperial Palace, and St. Isaac's Cathedral. Note that he himself does not approach these beauties, but bypasses them or observes from a distance. He belongs to a different St. Petersburg.

“He looked and saw an elderly woman from the merchant class, in a kerchief and goatskin shoes, with a young girl—probably her daughter—wearing a little hat and carrying a green parasol. ‘Take it, my dear, in Christ’s name.’ He took the money, and they walked on. It was a twenty-kopek piece.”

A few moments after he was lashed on the back by the coachman, the elderly merchant woman gave him alms. Note that it was 20 kopecks, the same coin Raskolnikov gave to save the drunken girl.

Money in the novel plays a metaphorical role — it is in a way a means of energy exchange, who helps whom and who accepts help. Raskolnikov establishes a hierarchy between himself and the world: he is the giver, but not the receiver. He believes that he gives money to others out of a sincere sense of compassion, but for some reason does not allow the same sincere compassion to be shown towards himself.

Raskolnikov is embittered by the world and cannot forgive the world for the good that exists in it: such simple, selfless goodness, and mercy from strangers (and not only from Razumikhin) destroys his convincing logic about the abnormality of the world order.

He is observing the splendid view before him and muses about a strange impression he gets from this seemingly lovely place. He feels the cold terminating from this place and a mute and deaf spirit permeating everything. Such a spirit is a gospel image of demonic possession (see: Mark 9: 25). Petersburg is a city of demons.

You can view a modern panorama from this bridge on Google Maps

At the same time, it is important to emphasize the contrasting perception of Raskolnikov's view of the "splendid panorama" visible from the Nikolayevsky Bridge, both before and after the murder. Thus, stopping while crossing the Nikolayevsky Bridge turns out to be a "crisis point" for Raskolnikov, in which he finally realizes the completed break with the world:

"It seemed to him that he had cut himself off from everyone and everything at that moment, as if with scissors".

Returned home (1 — on the map)

He walked around the city all day. At the beginning of this day, he was at the police station, then he went to hide the stolen things. And now he returned at dusk, that is, close to midnight. And then he had a nightmare that he could not distinguish from reality.

It seemed like the chief’s assistant — lieutenant Ilya Petrovich, nicknamed "Powder / Gunpowder" was beating his landlady on the stairs. Why so? Both of these people generally cause Raskolnikov discomfort, he lies to them and hides from them. He doesn’t pay rent to the landlady and avoids meeting her, and he has obvious fears regarding the police officer from whom he wants to conceal the truth about his crime. He can surrender to both of them, but he continues to struggle with his emotions.

Nobody came here. That’s the blood crying out in you. When the blood can’t get out, and starts curdling in your liver, that’s when you begin seeing things… So are you going to eat anything, then?

The words of Nastasya quite definitively correlate with the biblical words of God addressed to Cain (Genesis 4:10), as if presenting their colloquial equivalent.

The LORD said, “What have you done? Listen! Your brother’s blood cries out to me from the ground.

The guileless Nastasya uses the word "blood" in its folk interpretation: disease, fever, but the language of the common people turns out to be wiser than the speaker herself. As it was in the first chapter, when a passerby mocked Rodion's hat, calling him a German (what it really means for a foreigner who cannot speak) . And here for Raskolnikov, the words of this simple woman are the voice of the people, exposing him. He is increasingly losing his roots. He is imbued not with his own blood, but with a disease that devours him from within.

In such a painful state, we leave Rodion Raskolnikov until Monday. What do you think this blood means? Which came first: Rodion's illness or the crime? What triggered what?

Enjoy your reading!

To me there are two way to interpret this story: Raskolnikov is both guilty and innocent. Just like his name suggests, Raskolnikov inhabits opposites. He his a man who has committed a horrible crime and is undergoing a monstrous metamorphosis under the unforgiving eye of God. He is also a mentally ill man who has fallen through the cracks of society, like many before and after him. People used to ask, is a woman a human being? We now ask, are the mentally disabled human? Are the addicted? Criminals? Murderers? When does a person become a beast? When should we deny someone's humanity?

Take the whipping in the street: did Raskolnikov deserve it? He certainly was standing in the way. He was certainly not aware of doing it. He symbolically takes the place of the poor beaten horse and of Christ flagellated. But when he receives help and pity "in the name of Christ" he cannot accept it. He's haunted by the way people perceive him, convinced everybody is staring. For the second time he hides the stolen items and his guilt in a little hole of a very dark corner. And someone is always watching.

Since chapter 1, Raskolvnikov has been contemplating killing, in this chapter he has been dwelling on Jack the Giant Killer. He has been slipping into worse thought and actions ever since. Where does the crime begin? With the first thought? (I don't think so..thoughts appear in our heads unsummoned.). With using one's free will of repeatedly contemplating those thoughts, imagining killing the “giant” in one’s life? Or the actual slaying? There is something in US law about premeditated murder. So perhaps the crime begins with the conscious invitation to keep imaging the murder. But what is the “giant” in his life? I do not know. I think he has been in an increasingly chaotic mind since we met him. Yes, he is human, but at this point a deranged human. Which begs the question, is there evil, or are there just grossly misfiring neural connections?