5.5 The poor nag’s been driven to death!… I’m done for!

As you've noticed, Dostoevsky likes to end each part with unexpected turns, often associated with death. This time, we're again faced with a character's death...

Hello, Dostoevsky enthusiast!

List of articles by chapters you can find here

Reading schedule is here.

Let's recall how the events have unfolded so far:

End of Part 1 — Raskolnikov's crime: the murder of Alyona Ivanovna and her sister Lizaveta.

End of Part 2 — Marmeladov's tragic death under the wheels of a horse-drawn carriage, possibly a suicide.

End of Part 3 — Raskolnikov's dream, where his desire to kill the old woman resurfaces, but he fails. Death now mocks Rodion, appearing as a crowd of faceless beings.

End of Part 4 — Mikolka's unexpected confession to the murders. Rodion believes he has escaped justice, but punishment looms inevitable.

End of Part 5 — The death of Marmeladov's wife, Katerina Ivanovna. She succumbs to illness, leaving her three children orphaned in the care of her stepdaughter Sonya.

During Sonya and Rodion's heartfelt conversation about his crime, Lebeziatnikov bursts in with news of Katerina Ivanovna's mental collapse. This occurs on the very day of her husband's funeral. After quarreling with everyone—particularly Amalia, her landlady—Katerina fled into the street mere hours ago. In a desperate attempt to seek justice as she perceives it, she confronts her late husband's former employer, predictably without success. Following a final altercation with the landlady, Katerina takes to the streets with her children, begging for alms. Her intent is to shock onlookers: "Let them see how the noble children of a government official are forced to walk the streets!" Sonya rushes to intervene, while Raskolnikov retreats to his cramped room.

A Stranger Among His Own

"Never, never before had he felt so terribly alone!" Why? He had just received Sonya's assurance that she would never leave him—and that means so much! Yet he doesn't need Sonya's love right now; he feels he might even come to hate her. He despises himself for going to Sonya, as it seems to him, "to beg for her tears." And now Sonya has run off to her own people, while he has no one. But why?

He has relatives—yet he has cut himself off from them. At this very moment, his sister comes to him. "And she too came with love for him"—that's all Raskolnikov feels. Dunya doesn't yet know about her brother's crime, but she senses his torment (attributing it to unfair suspicions from Porfiry and others) and offers him, if needed, the most precious thing a person can offer—her life. But Raskolnikov doesn't need this either; there is still a wall between him and those closest to him. He wants to embrace his sister but hesitates, thinking about what will happen when she learns that he is a murderer.

"Later, perhaps, she'll shudder when she remembers that I embraced her now, she'll say that I stole her kiss."

In terrible anguish, he sets out to wander the streets, anticipating "the hopeless years of this cold, deadening anguish," an eternity "on an arshin of space." On the street, he stumbles upon the almost deranged Katerina Ivanovna and her children crying in horror, whom she forces to sing and dance, begging for alms.

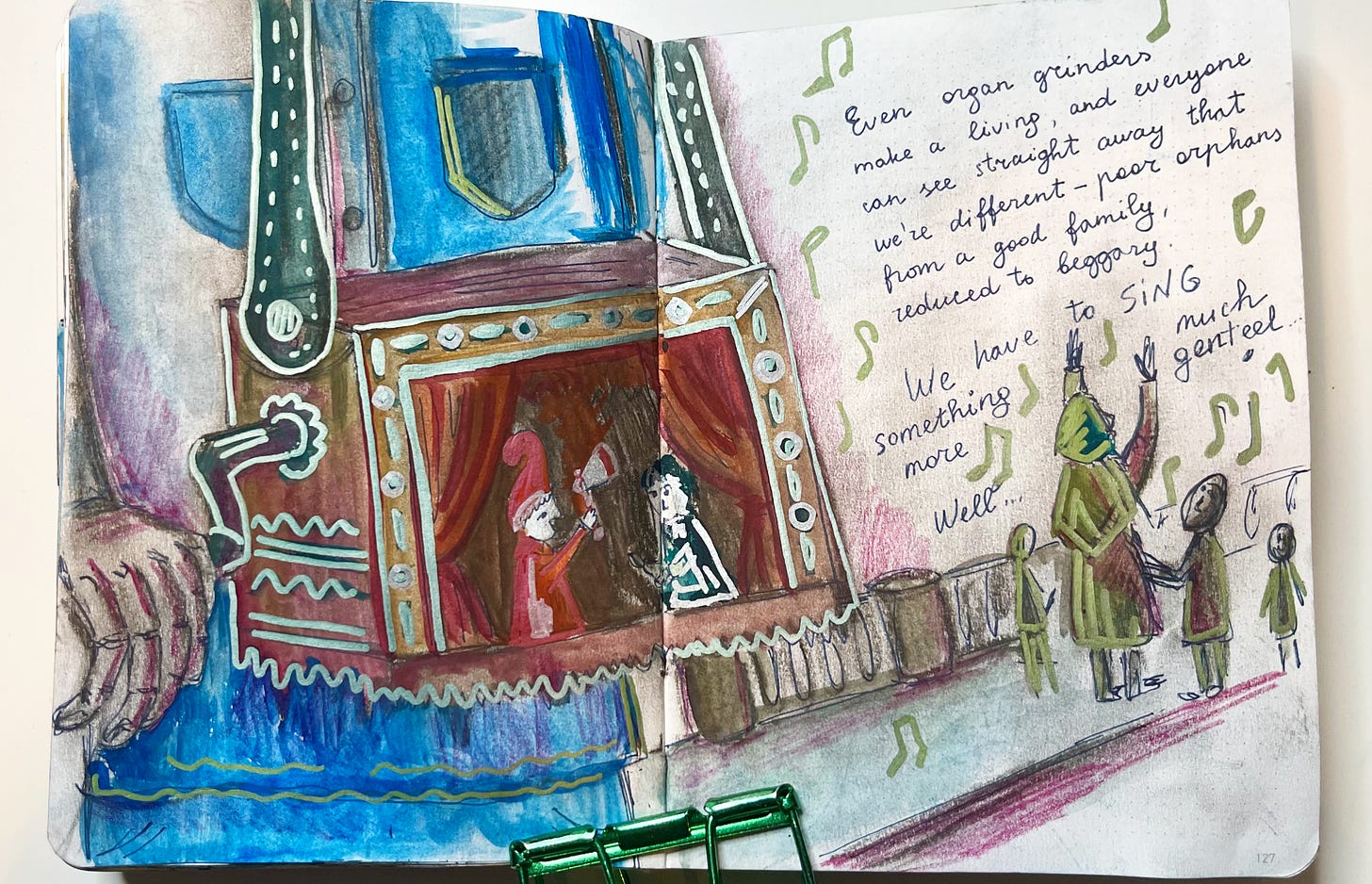

"Petrushka" (Петрушка)

we're not performing some kind of Petrushka show in the streets...

Petrushka is a popular character in Russian folk puppet theater. Besides being a character in fairground performances - the carnival Petrushka - from the 1840s, the so-called "walking" Petrushka, performed by street organ grinders, became widespread in cities. You can read more about it here

In the 1860s, these performances typically unfolded as follows: An organ grinder would arrive with puppets and erect a screen in the courtyard's center. Common folk—janitors, lackeys, washerwomen, and coachmen—would gather to watch. Petrushka would emerge from behind the screen, launching into his comedic routine. After the show, spectators would reward the organ grinder with money or food.

Petrushka comedy is known for its coarse, folksy humor and the overall aesthetic of street puppet shows. This is precisely why Katerina Ivanovna speaks of it so disparagingly—she still views herself as a member of the nobility, above the common people around her. Herein lies her tragedy: she refuses to assimilate into the surrounding working class. This pride likely explains why she didn't take up work as a laundress or cook herself, but instead pushed Sonya into prostitution.

Folk Music

This chapter is full of musicality, although it is created by the deranged Katerina and she forces her unfortunate children to play. Music is also a kind of voice of the people, passed down from century to century, from mouth to mouth.

This is from the film "The Road to Calvary," and it's not entirely related to our novel, but this film excellently depicts an organ grinder (шарманка, sharmanka) and singing along to it. This is already the beginning of the 20th century, but the atmosphere is similar. Therefore, I invite you to watch this short clip. This could have been Katerina Ivanovna as well.

In Petersburg at that time, there were indeed many organ grinders (шарманщик), and not long ago a monument was even erected to one.

Oh, let's sing "Cinq sous" in French!

"Cinq sous" is the refrain of the song "The Dowry of the Savoyard Bride" (la Dot de Savoie) from the melodrama "God's Mercy" (La Grâce de Dieu — Adolphe D’Ennery - Gustave Lemoine), which the poor characters Maria and Pierrot sing in the house of the Marquise de Sivry. Under the title "The New Fanchon" ("La nouvelle Fanchon"), the play was performed by the French troupe of the Mikhailovsky Theatre in St. Petersburg and the French theatre in Moscow, starting from 1842. Songs from "The New Fanchon" remained popular in Russia for a long time.

"Marlborough s'en va-t-en guerre," as it's a completely childish song and is used in all aristocratic homes when lulling children to sleep

An old French humorous song "Marlborough Has Gone to War," which owed its initial popularity to the fact that it was greatly liked by Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette when the wet nurse sang it to lull the Dauphin to sleep.

The song gained widespread popularity in France and was translated into various languages, including Russian, by the late 18th century. During the Patriotic War of 1812, it experienced a resurgence in Russia, as the ironic tale of Marlborough's failed campaign was seen as an allegory for Napoleon's defeat.

In the Russian adaptation, which mocked Marlborough's unsuccessful Russian campaign, the commander meets a "shameful death" not in battle, but from fear-induced bouts of diarrhea. Pushkin and his lyceum friends even composed a parody of the Marlborough song during Napoleon's invasion of Russia. The song spread among soldiers, evolving significantly and acquiring crude elements. It became a staple in organ grinders' repertoires.

Katerina Ivanovna clearly intends to perform the "canonical" French version with her children. However, the existence of a well-known, satirical Russian street version creates a tragicomic situation: it highlights the gap between Katerina Ivanovna's aristocratic self-perception and her harsh reality. For "Crime and Punishment" the Marlborough-Napoleon allusion that became part of the Russian tradition seems particularly significant.

Ophelia's Death Song

Du hast Diamanten und Perlen...

According to the memoirist Von Focht, in the summer of 1866 in Lublin, where the writer was resting with his sister's family while continuing to work on "Crime and Punishment," "once in the presence of F. M. Dostoevsky" he "played on the piano a German romance based on famous verses by Heine:

You've pearls and you've diamonds, my dearest,

You've all that most mortals revere;

And oh, your blue eyes are the fairest —

What else could you ask for, my dear?1

I suggest listening the music from this romance. It's truly a beautiful melody.

"Fyodor Mikhailovich liked this romance very much and was curious about where I had heard it. I replied that I had heard it played several times by organ grinders in Moscow. Apparently, Dostoevsky was hearing this romance for the first time and began to hum it quite often himself." Later, "as a result of this, he had the idea ‹...› to put the same words of this romance into the mouth of the dying Katerina Ivanovna Marmeladova, which she utters in her delirium"

The death song of the insane Katerina Ivanovna alludes to the dying song of the mad Ophelia in Shakespeare's tragedy. In Dostoevsky's work, tragedy is woven into ordinary prose. When the grief-stricken widow Marmeladova sings the tender romance "Du hast Diamanten und Perlen," this technique echoes "Hamlet": the German romance becomes a symptom of her madness and impending doom—the "Ophelia symptom," if you will. Through such methods, Dostoevsky elevates mundane everyday life to the level of tragic myth, revealing that myth is present in the everyday.

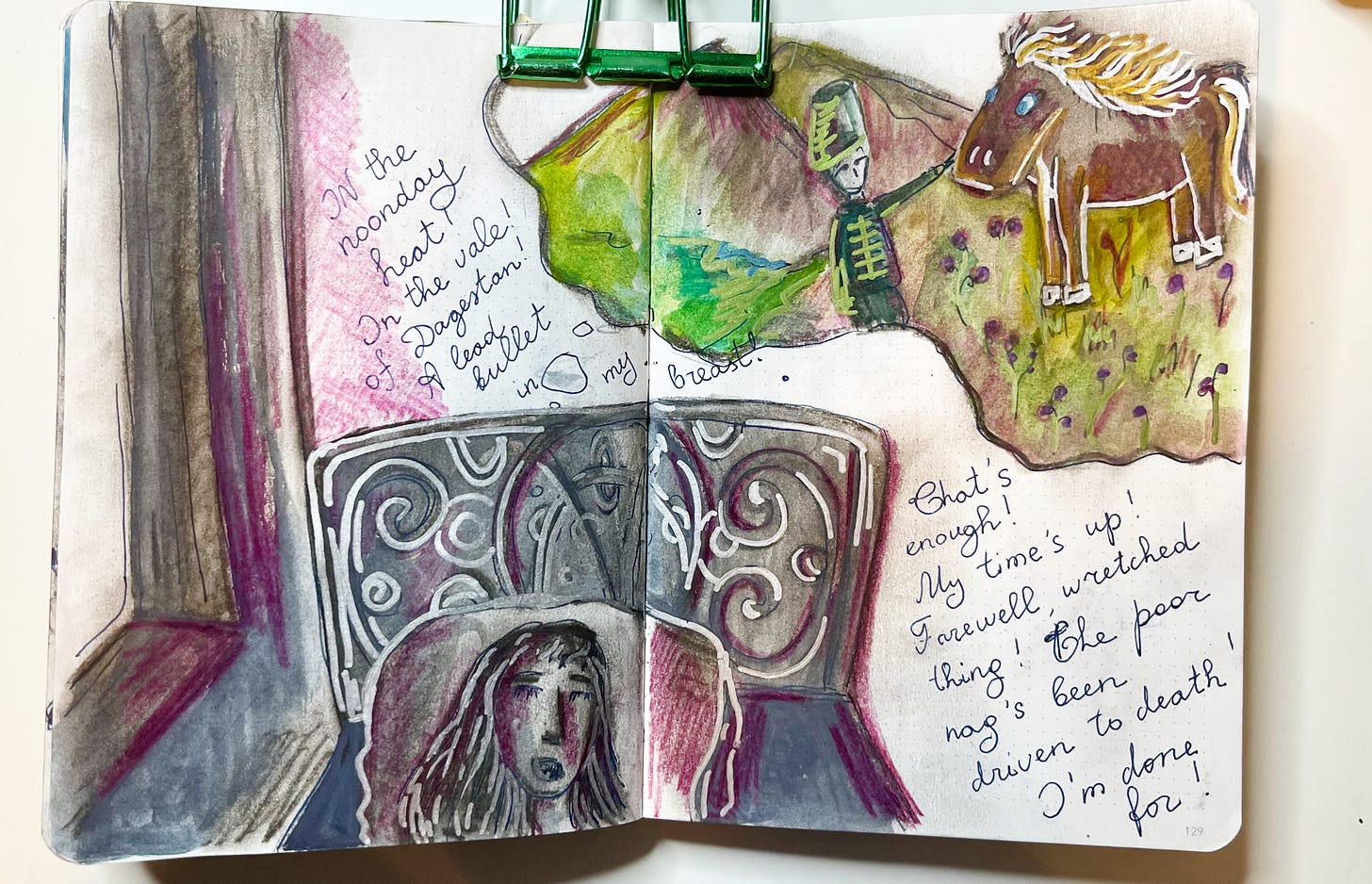

In the midday heat, in a Dagestan valley... (В полдневный жар, в долине Дагестана... )

A romance based on the poem "The Dream" (Сон) (1841) by M.Y. Lermontov. According to Katerina Ivanovna, her first husband used to "sing" this romance when he was still her "fiancé". It is the thoughts of her first love and the life she could have had with him that remain the last in her consciousness.

Here you can read the text in Russian and in English translation.

This poem is about death, dream, and sleep. Similar to the meaning of the French word "rêve". That's why it's not by chance that Katerina Ivanovna thinks about this poem and romance in the last minutes of her life. She is in this simultaneous state of death, dream, and sleep.

Refusal of Confession

It all ends with Katerina Ivanovna falling in the street, bloodied, and Raskolnikov, along with others, helps carry her into Sonya's room, where she dies on Sonya's bed.

Katerina Ivanovna refuses a priest and confession before death, which is unusual for a believer. We cannot say that Katerina was an atheist. Did she lose faith? Possibly. But most likely, her resentment towards an unjust world comes into play again. And we shouldn't forget that she has gone mad.

"I have no sins," she says, lying on the bed of the girl whom she herself sent to the street, to the perdition of her soul. "God must forgive without that!.." and she dies with the words: "The poor nag’s been driven to death!… I’m done for!”

We can draw a parallel with Rodion's dream about the beaten horse (described in chapter 1.5). Katerina Ivanovna sees herself as that horse, mercilessly beaten by the world without reason, helpless to change her fate. In her view, no one comes to her defense. Just as Rodion couldn't save the horse in his dream, he's powerless to help Katerina or her children. Assistance will arrive from an unexpected source.

Life itself repeatedly undermines Raskolnikov's theory, yet evil clouds his vision like a veil, blinding him to this reality. Though he commits his crime with the supposed aim of helping others, after the murder he craves solitude, constantly wanting to be "alone, alone, alone!" He claims to act for the sake of the "eternal Sonechka," yet the real Sonya utterly rejects his right to commit crime. She even recalls, with horror, the money Raskolnikov left for her family, wondering if it came from his ill-gotten gains. Her reaction is natural—no person of conscience would accept blood money, even in the direst circumstances.

Svidrigailov emerges from the crowd, stunning Raskolnikov. First, he promises to place Katerina Ivanovna's children in reputable orphanages and provide for them financially. Even more shocking, he reveals to Raskolnikov that he overheard all his conversations with Sonya.

This marks the beginning of the final act in Raskolnikov's tragedy. It's crucial that we grasp this part correctly, as it's dense with events. Dostoevsky typically becomes more concise towards the end of his novels, relying heavily on his readers' astuteness.

Are you ready to read the final part of the novel?

Next time we'll discuss the first two chapters right away, as nothing particularly significant happens in the first one - it's the last respite before very intense chapters, some terrifying, some filled with hope.

Original:

Du hast Diamanten und Perlen,

Hast alles, was Menschenbegehr,

Und hast die schönsten Augen, -

Mein Liebchen, was willst du mehr?..

Translation — https://www.poetrynook.com/poem/du-hast-diamanten-und-perlen

Thank you for all the musical links, they really gave more flavor to the chapter. Marlborough goes to war's melody reminds me of For he's a jolly good fellow, just a little.

I always took notice of how Katerina Ivanovna kept washing herself, and washing the children and their clothes. As if she wanted to keep them all clean from the life she deemed inferior. But also it parallels Rodion washing the axe and his clothes after the murder, so, guilty conscience on Katerina Ivanovna's part too? Would such a thing be possible, would have nobody stepped in to help those children back then? Even before she had her mental breakdown, if not the government, wouldn't there have been a church or some place religious that could have intervened? The way the crowd just stared as she spat blood and abused the children was horrifying. Is the behavior of the crowd supposed to be realistic or metaphoric?

I want to know more about Svidrigailov, what is he doing, what's his plan? So far we've only learned bad things about him. Change of heart, or is he luring Rodion into a trap?

Thank you so much for the section on music in the chapter! The videos made those portions come alive! I was shocked to know the melody of the song Marie Antoinette liked. We sing it as “For he’s a jolly good fellow.” I did some quick research, and it is said to be the second most recognizable tune in the world, bested only by “Happy Birthday.”

I am so excited to finish the novel. I’m a tad concerned that I won’t be able to restrain myself to keep on schedule. 🤭