Who is von Sohn? The Story of a Monstrous Crime

An article without spoilers for The Brothers Karamazov, although this name is mentioned there. It's about a horrific and notorious murder from 1869.

Dear Dostoevsky enthusiasts!

We're halfway through reading and discussing the second book of The Brothers Karamazov — Schedule and materials

Today's article takes a different approach—instead of plot analysis, we'll explore a true crime story. Don't worry—this article won't spoil the novel.

Dostoevsky frequently wove real criminal cases into his novels. You'll find several such references in Crime and Punishment, The Idiot mentions notorious murders, and The Brothers Karamazov continues this tradition.

We'll examine a fascinating crime from 1869 Petersburg that's rarely discussed in English sources. The case became a sensational trial in 1870, captivating the city's attention. Today, we remember it primarily through Dostoevsky's literary references to his contemporary world.

I invite you all to join our discussions—we maintain a relaxed atmosphere in our community chat.

So who is this "von Sohn" (фон Зон)?

When Fyodor Pavlovich Karamazov sees landowner Maximov at the monastery, he calls him "von Sohn." This creates an interesting anachronism—the real von Sohn case (the death of Nikolai Khristianovich von Sohn) occurred and went to trial in 1869–70, while the novel's action takes place in 1866, with the narrator writing in 1879. This leaves us with two possibilities:

Either the narrator has inserted these words into Karamazov's mouth, and they were never actually spoken,

Or The Brothers Karamazov operates with its own sense of time, much like its treatment of space. Just as real places are repositioned (for instance, the Optina Monastery appears next to Staraya Russa, though they're actually 650 kilometers apart), the novel may also take liberties with chronology.

I favor the second interpretation, as Dostoevsky frequently employed such anachronisms in his novels. After all, this is a work of fiction rather than a historical chronicle, and the precise timing of real events need not constrain the novel's narrative.

What happened to von Sohn?

On November 8, 1869, Elizaveta Nikolaevna von Sohn reported to the St. Petersburg police that her husband, Court Councillor Nikolai Khristianovich von Sohn, age 62, had vanished. He had attended the Noble Assembly on November 7 and never returned home.

The Noble Assembly handled local community matters but was prohibited from discussing state governance. You can read about the Noble or Aristocratic Assembly here.

The police investigation yielded few leads until December 1869, when a young man named Alexander Ivanov came forward. Burdened by guilt, he confessed that von Sohn had been murdered and admitted his own involvement.

As confirmed by his wife's account, von Sohn had gone from the Noble Assembly to his regular haunt—the Eldorado café, a casino. There, in the late hours of November 7-8, he encountered Maxim Ivanov and two prostitutes, Big Sasha and Little Sasha, who invited him to their brothel on Spassky Lane.

All of this, by the way, took place in the area of Sennaya Square (or Haymarket). Those who have read Crime and Punishment will remember this place well—it's the exact district where all the novel's characters lived.

Initially, von Sohn declined the invitation, being quite intoxicated and wanting to return home. However, Maxim Ivanov lured him by promising time with an innocent thirteen-year-old girl. Unable to resist this deplorable offer, the retired Court Councillor accompanied the group to Spassky Lane, where they indeed found a young girl named Elena Dmitrieva.

The apartment's residents included:

prostitutes Alexandra Avdeeva and Alexandra Semyonova (known as Big Sasha and Little Sasha),

Alexander Ivanov (a craftsman who shared Maxim's surname but was unrelated),

Anton Grachev and Ivan Fedorov — peasants who served as household workers,

and Darya Vasilyeva, Maxim Ivanov's lover.

More vodka flowed, and the already inebriated von Sohn drank heavily. The encounter soured when Elena, disgusted by the drunk old man, fled. As von Sohn prepared to leave, Big Sasha pickpocketed his wallet. Upon discovering the theft in the street, he fatefully decided to return.

A Senseless Murder

Von Sohn returned to demand his money back. Maxim Ivanov tried to dismiss it as a joke and suggested they drink to make peace. They offered Nikolai Khristianovich a glass that, according to Maxim, contained poison—though for some reason it didn't take effect immediately. Then almost all the apartment's occupants attacked him. They threw a blanket over his head, strangled him with a belt, and beat his head with an iron, while Avdeeva sang, stomped her feet, and pounded on the piano keys to drown out his screams. The other residents dismissed the commotion as mere drunken revelry, and no one called the police.

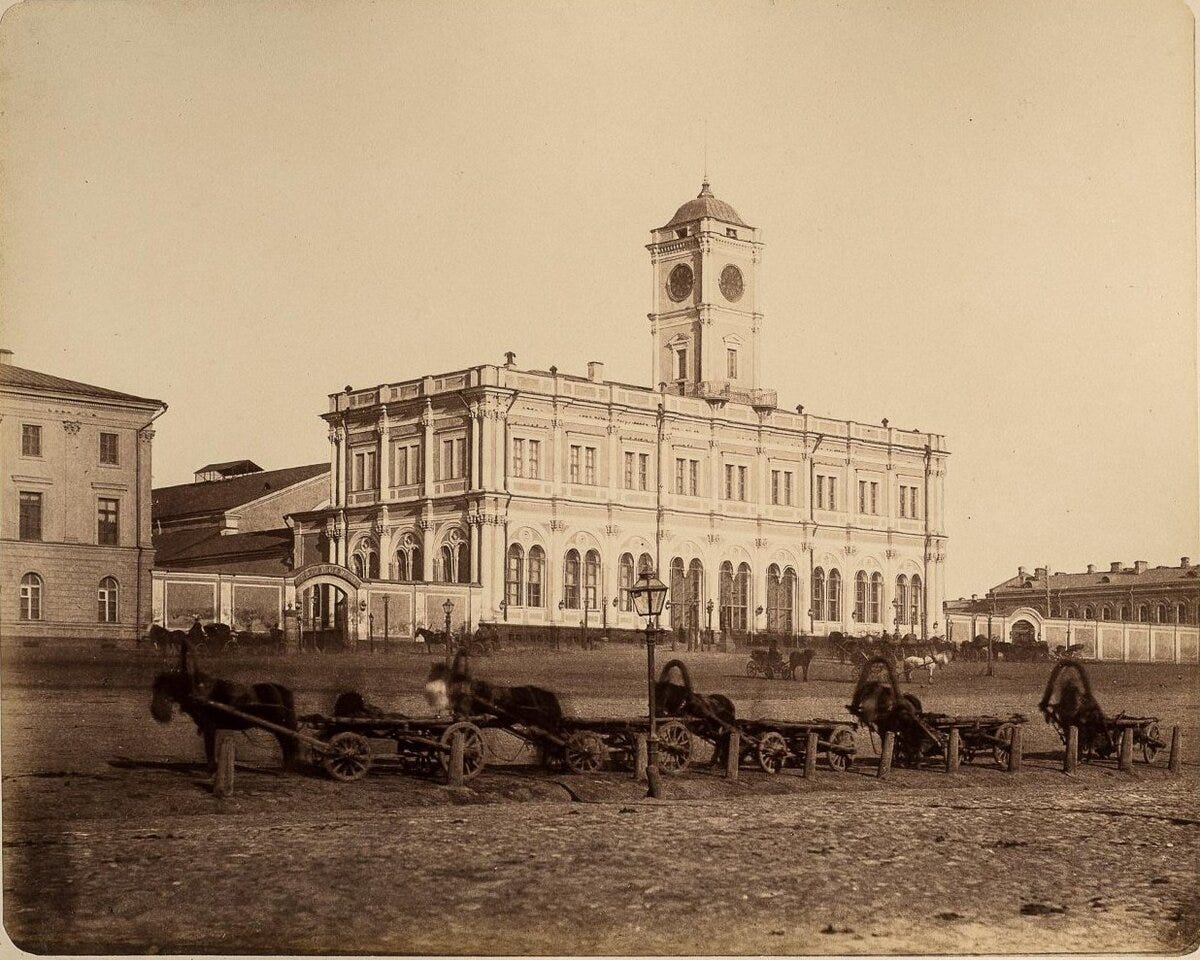

To dispose of the body, the accomplices devised an unusual plan: they purchased a large traveling trunk, placed the corpse inside, and sent it to Moscow by train under a fictitious name.

The body was later discovered at Moscow's Nikolaevsky Station in the unclaimed baggage area. Only when officials opened the trunk did they find von Sohn's remains. It remains unclear why the body wasn't discovered earlier—whether the stench of decomposition went unnoticed, or if such odors were simply commonplace in those years.

The murderers split von Sohn's money, though the sum proved meager—each received only 5 to 10 rubles. Avdeeva, despite her significant role in the crime, got merely 5 rubles, which her pimp promptly confiscated.

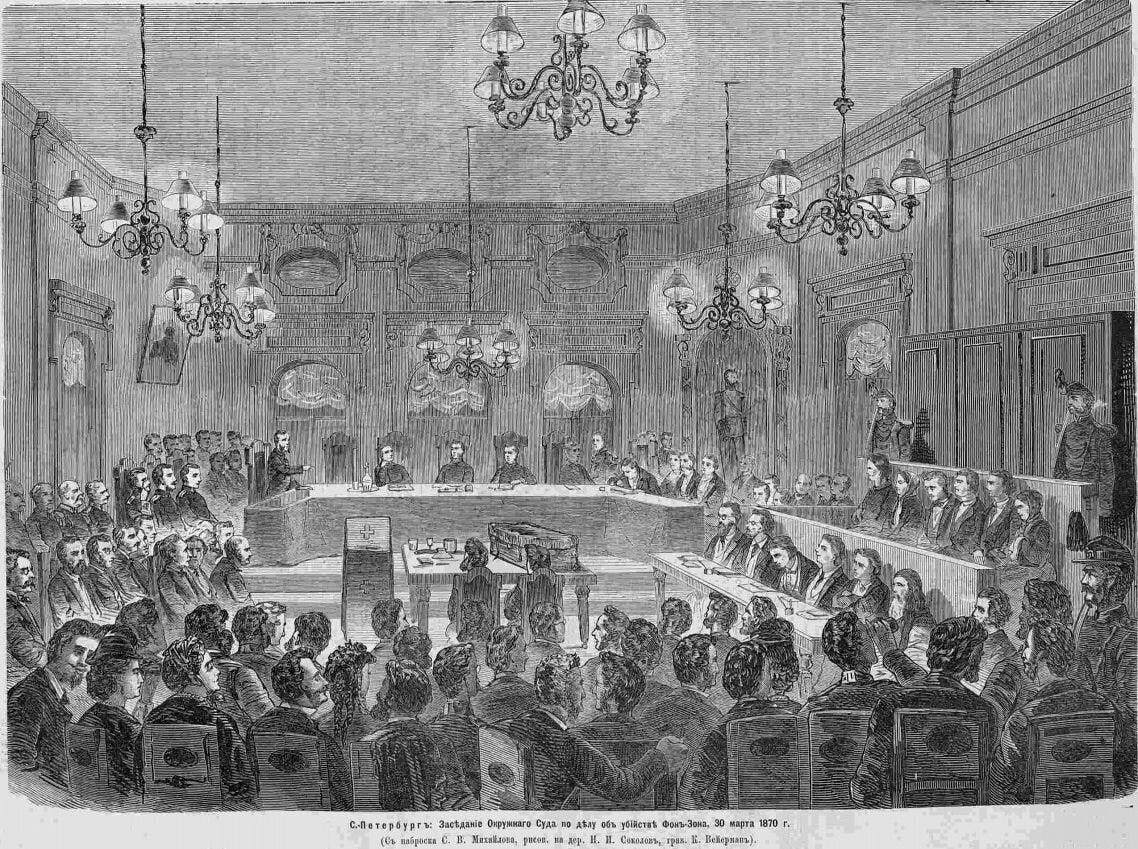

The case went to trial in Petersburg in March 1870. It generated immense public interest, with extensive newspaper coverage. The courtroom was open to spectators, and many eagerly attended the proceedings.

The Trial

The trial for this case took place in March 1870. Six defendants sat in the dock—Maxim and Alexander Ivanov, Avdeeva, Grachev, Fedorov, and Vasilyeva. Interestingly, since the defendants lacked sufficient means, the court appointed their defenders. These turned out to be true stars of the legal profession at the time, as the case was high-profile: Pavel Potekhin, Konstantin Arseniev, Vladimir Spasovich, Vladimir Gerard, Alexander Yazykov, and Konstantin Khartulari. The Ministers of Justice and Foreign Affairs, and even Grand Dukes, were present in the courtroom.

However horrifying the details of the case were, especially the description of the murder scene, the lawyers pointed out that the crime was not the result of careful calculation or a well-developed plan. None of the participants possessed either sophisticated intelligence or any other outstanding qualities. Even the ages of the defendants didn't suggest experienced criminals:

Maxim Ivanov, the oldest, was only 26

Avdeeva was 17

Grachev was just 16

Vladimir Spasovich, who defended Avdeeva, said:

Consider now, do you see what kind of subject this is? She has diminished under careful examination. Instead of a terror-inducing monster, instead of a demon, instead of a woman driven by powerful passion, what we actually find is merely a being barely resembling an underdeveloped human, who can only be dealt with as with an unreasoning animal.

This woman, one cannot say she is completely incapable of development, of reformation; you have heard that her account is quite sensible... and if she faces the punishment that threatens her, I think this punishment will still be beneficial for her, because it cannot fail to affect her. The position that will be created for her by your verdict, however terrible it may be, will still be better than the position she was in with Maxim Ivanov.

In the end, the court sentenced:

Maxim Ivanov to 12 years of hard labor,

Alexander Ivanov (who turned himself in to the police before the body was discovered and helped locate it) and Ivan Fedorov to 4 years

Avdeeva was exiled to Siberia for settlement

Grachev, being a minor who committed the crime "without full understanding," was sentenced to 3 years imprisonment

Vasilyeva to 8 months.

Journalists present at the trial noted that all defendants received their sentences very calmly.

Maxim Ivanov, not waiting for the court's decision, hanged himself in his prison cell using a bed sheet.

Another curious fact is that the expert witness at the sensational von Sohn murder trial was the chemist D. Mendeleev—the very same one who is considered the creator of the periodic table of elements as we know it today.

Karamazov remembers this von Sohn - the retired Court Councillor Nikolai von Sohn - when he sees Maximov. Why?

Dostoevsky deliberately gives this character the surname Maximov, echoing the name of von Sohn's real murderer—Maxim Ivanov.

Von Sohn, though a murder victim, was a notorious figure. His biography, revealed during the trial, showed him to be an elderly libertine from the Noble Assembly, a position of authority. This combination of moral corruption and official power made him particularly despised among common people.

The scandal surrounding the murdered von Sohn affected another unrelated von Sohn who lived in Staraya Russa—the city that served as the prototype for the Karamazovs' hometown. This other man, Karl Karlovich von Sonn, was an honorary Major General who managed the local sawmill and flour mill factories, and served as Police Master of the salt spring baths.

For contemporary readers, the mention of von Sohn in the novel offered multiple layers of meaning. Some would recognize him as the man who brought shame to his family name before becoming a murder victim. Others might think of the respected von Sohn of Staraya Russa, whose reputation suffered through mistaken association.

At its core, von Sohn represents a disappeared official whose lustful nature led to his demise—a parallel that Karamazov might have recognized in Maximov.

Excellent Research

Thank you for this wonderful insight

Thank you for this article. When you discussed the context of St Petersburg, a thought came to me about Dosto’s novels. I have read the five great novels except for TBK, and I noticed that in all, the cities and particularly St Petersburg seem to emanate moral decay and spiritual evil. Yet (spoilers) it can also be a place of glorious redemption, as the Haymarket is in Crime and Punishment. I find this to be a really enchanting setting or context for his fiction.