Let's reflect on Book 3: Smerdyakov's role, money, the love triangle, and Schiller

We have read Book 3 (out of 12) of The Brothers Karamazov novel. And it's time to discuss some points in more detail.

Hello!

All materials and schedule can be found here

Some key aspects of Book 3 that warrant further exploration.

As we prepare to begin Part 2 of the novel next week, I'd like to wrap up some important threads from Part 1. Today, I'll examine three aspects of Book 3 that deserve closer attention:

Smerdyakov's role (though this is just the beginning, as we have nine books ahead),

Dmitri's financial situation (which continues to evolve throughout the story), and

Dostoevsky's frequent references to Schiller.

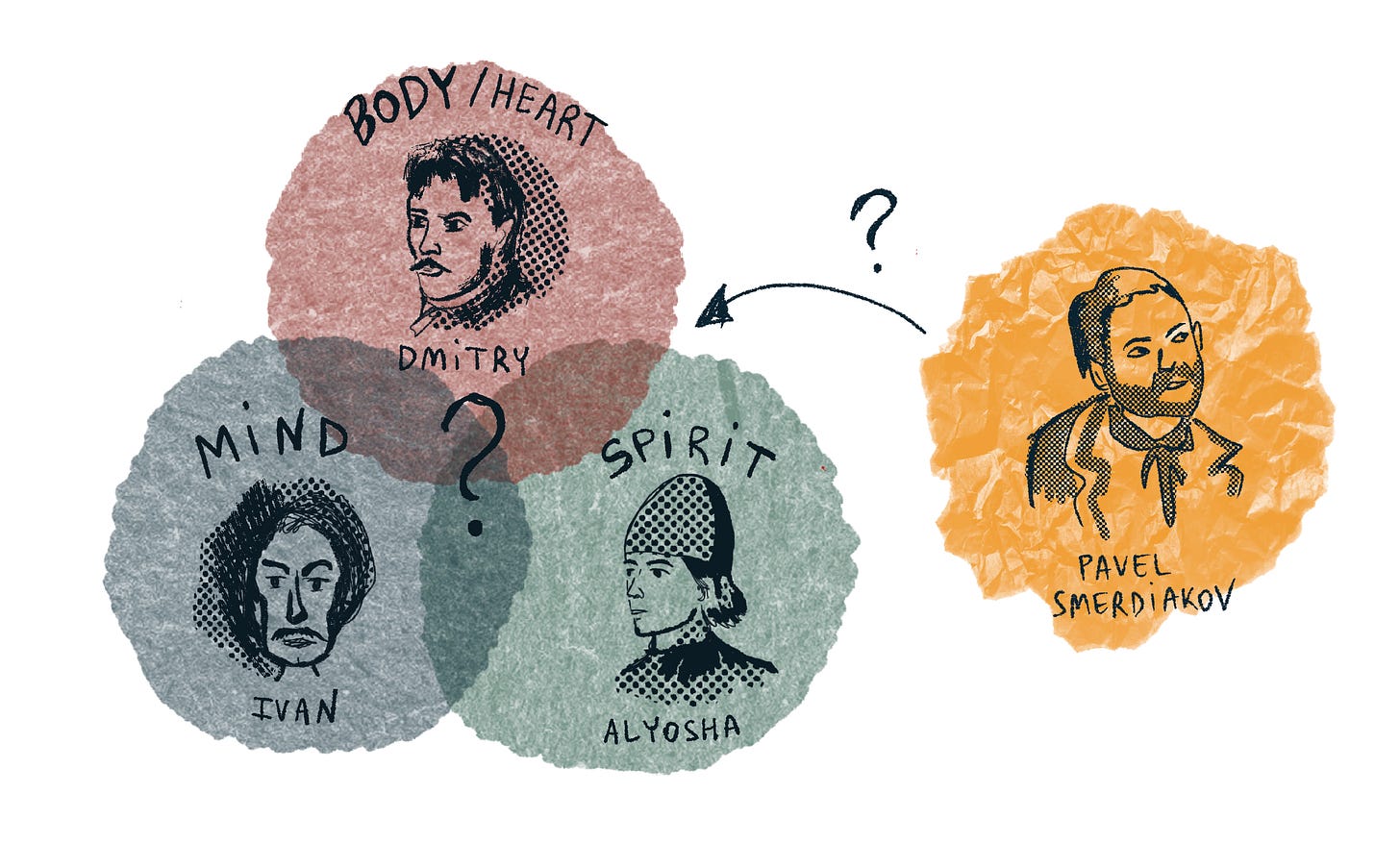

Smerdyakov: Brother or Not?

We are reading a novel called The BROTHERS (!) Karamazov. Fyodor Pavlovich Karamazov—the father—serves not so much as a main character but as a catalyst, uniting our heroes through their birth, bonds, and conflicts. As for the brothers' mothers, all died early, leaving none of the brothers with lasting maternal care. Ivan fared best, with Sofya Ivanovna living until he was 8. Alexei was 4 when his mother died, while Dmitri was only 3 or 4 when his mother first fled to Petersburg and later died. Smerdyakov's situation proved even bleaker. His mother died giving birth to him.

Should we, then, count Smerdyakov among the "Karamazov brothers"? Let's examine the similarities that suggest his place as the fourth brother.

Let's assume that Smerdyakov is Fyodor Pavlovich's biological son. Even if he isn't, Smerdyakov lived in Fyodor Pavlovich's house his entire life, observing him more closely than any of the other brothers. Which matters more—nurture or nature?

Like all the children, he was raised by Grigory (and Marfa) in his early years, though some received more attention than others.

He bears the patronymic Fyodorovich. Names carry weight. And uniquely among the sons, his name Pavel mirrors his father's patronymic (Fyodor Pavlovich) and follows the honored family tradition of naming sons after their grandfathers—a mark of true lineage.

While he lacks formal education, he's far from stupid—much like Dmitri.

He might have carried the Karamazov surname had Fyodor Pavlovich wished it. Instead, they gave him a new surname linked to his mother. Ironically, though Smerdyakov never knew her, his name carries more of his mother's legacy than any of his brothers' names do.

If Smerdyakov is indeed the fourth brother, how does he fit into the balance among the brothers? His identity poses a complex question—while he may be a brother by blood, he clearly stands apart, born and remaining a servant. Do the Karamazovs avoid acknowledging him as their brother?

Rather than viewing Smerdyakov's brotherhood as taboo, we might better understand it as a test. No divine law prevents the others from embracing him as a brother; their failure to do so stems purely from human weakness. As Zosima told Madame Khokhlakova, "active love compared to dreamy love is a harsh and frightening thing... active love is labor and perseverance."

Smerdyakov's crude nature makes this challenge particularly difficult. Through him, Dostoevsky tests his characters, linking the novel's main action to the philosophical core of "The Grand Inquisitor." We'll explore this connection further in May, so keep Smerdyakov's nature in mind.

By making Smerdyakov so difficult to love, Dostoevsky heightens the moral value of accepting him. His base character amplifies the significance of universal brotherhood, demonstrating how far such love must reach. Loving the virtuous Alyosha requires no moral strength.

Dmitri, less given to introspection than his brothers, never considers whether his treatment of Smerdyakov as a mere servant is just. This attitude not only diminishes his brother but contradicts Elder Zosima's teaching that one must become a servant to one's servant. Dmitri dismisses Smerdyakov as a "lackey"—and surprisingly, even Alyosha follows this pattern of behavior.

Among all the Karamazov brothers, Ivan understands Smerdyakov's essence most deeply. What explains this profound connection?

They share the same moment in time—Smerdyakov, though slightly older, was born in the bathhouse just as Sofya Ivanovna became Karamazov's wife, already carrying Ivan.

Their characters and worldviews mirror each other. Both are contemplative souls—Smerdyakov known for his meditation, Ivan for his keen observation and all-encompassing awareness.

They share a nihilistic philosophy, though their differences will become clearer as the story progresses.

Their mothers' fates intertwine—both Lizaveta Smerdyashchaya and Ivan's mother Sofya were homeless women deemed mad, though in different ways. Lizaveta was a holy fool, while Sofya was a religious fanatic. Their destitution sets them apart from Dmitri's mother.

Is Smerdyakov perhaps Ivan's shadow self?

Examining Smerdyakov's mystical origins suggests he embodies a trial for the Karamazovs—perhaps even the devil incarnate. Consider the signs: his birth in the bathhouse, his mother's death in childbirth, and the simultaneous death of Grigory and Martha's six-fingered child—the "dragon." Even his parentage—born to a libertine and a holy fool—echoes the prophecy of the Antichrist's birth to a harlot and a righteous man.

How does Smerdyakov view his place among the Karamazov brothers? Does he see himself as their equal? While we'll explore their kinship further, consider for now: what unique dynamic does Smerdyakov bring to this brotherhood?

Dmitri's Money or Passion

Money—both the desire for it and the inability to manage it—emerges as one of the central vices and troubles in the novel. This trait manifests most clearly in both Fyodor Pavlovich and Dmitri.

The specific monetary amounts in the novel hold less importance to Dostoevsky than their symbolic value; he frequently employs similar sums, often incorporating the number three. Rather than representing mere financial transactions, money in Dostoevsky's work functions as a conduit for energy exchanges. This energy dynamic forms the foundation of the love triangle involving Dmitri Karamazov, Katerina Ivanovna, and Grushenka.

Let me explain in detail.

Katerina Ivanovna falls in love with Dmitri following what she sees as his selfless act—giving her father 4,500 rubles as an outright gift, not a loan. Upon receiving her inheritance, she repays Dmitri the full 4,500 rubles and chooses to become his fiancée. Their relationship thus blossoms through this exchange of monetary energy, which initially serves a positive purpose.

The situation shifts when Fyodor Pavlovich Karamazov, opposed to his son's marriage to Katerina Ivanovna, transfers a promissory note in Dmitri's name to Grushenka. Facing the prospect of debtor's prison instead of marriage, Dmitri resorts to confronting Grushenka. Here is Mitya's own account to his brother Alyosha:

Just before I went to beat Grushenka, that very morning Katerina Ivanovna summons me and, in terrible secrecy, so that no one would know (why, I don't know, apparently she needed it that way), asks me to go to the provincial town and send three thousand rubles by post to Agafya Ivanovna in Moscow, through that town so no one here would know. So there I was with these three thousand in my pocket when I ended up at Grushenka's...

Isn't Katerina Ivanovna's request peculiar? Why would she need to send money to her sister secretly through another town?

The answer becomes clear upon reflection: the money was meant to return to Skotoprigonyevsk (Karamazov's city), intended for Mitya to pay off his promissory note debts.

Consider Katerina Ivanovna's predicament: her fiancé faces debtor's prison, yet she cannot give him money directly—his pride would prevent him from accepting it, especially while he awaits settlement with old Karamazov. Sending it from their town is equally impossible—if word spread of her sending money and Mitya receiving the same amount, local gossip would wound his pride. Her only option is to send the money through another town and instruct Agafya Ivanovna precisely how to handle it.

This reveals a crucial point: Katerina Ivanovna had devised a way to help Mitya without wounding his pride. Yet her plan failed when Mitya spent the money carousing with Grushenka in Mokroye instead of sending it to Moscow.

Dmitri breaks off his engagement with Katerina because he cannot repay these 3,000 rubles meant for her sister.

This love triangle, then, forms, endures, and ultimately collapses due to Dmitri Karamazov's mishandling of money. Yet there's more—each character has their own relationship with money: Katerina Ivanovna views it as a means of selfless love (if such a thing exists) and aid, while Grushenka simply desires wealth and wealthy men.

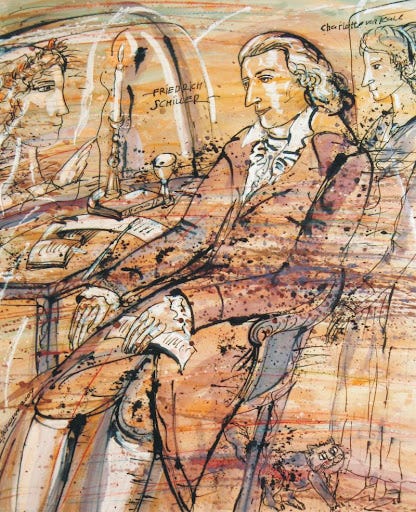

Schiller in the Words of the Karamazovs

F. Schiller significantly influenced the formation of Dostoevsky's intellectual, moral, and creative personality—the German classic was dear to him both as a person and as a creator. Here is a notable fragment from his letter to his brother Mikhail:

"...I memorized Schiller, spoke through him, was delirious with him [...] and Schiller's name became familiar to me, like some magical sound evoking so many dreams."

A striking example appears in Fyodor Karamazov's speech, where he accuses the elders of hypocrisy: "...We know these bows! 'A kiss on the lips and a dagger in the heart,' as in Schiller's 'The Robbers.'" While these words originally belong to the noble Karl Moor in Schiller's work, they take on an ironic twist when spoken by the cynical old Karamazov.

The father's references to literature are rich with contradictions. His very use of Schiller creates a comically revealing contrast—a true oxymoron. This extends to how he misidentifies his sons with characters from The Robbers, casting Ivan as the noble Karl Moor and Dmitri as the scheming Franz.

This pattern continues in his references to Intrigue and Love, where he absurdly casts himself as the young, noble Ferdinand while assigning his robust son Dmitri the role of the weak Court Marshal. These literary quotations in Fyodor's speech serve a deeper purpose—they become tools of self-revelation within Dostoevsky's carefully constructed moral framework.

Schiller's poetic works take on special significance when they inspire Dmitri at his life's crossroads ("Now the world has taken a new street"). Though these lofty texts might seem at odds with Dmitri's self-proclaimed nature as a "voluptuous insect," they speak to his deeper humanity and his destroyed ideals. Facing his past with contempt, he sees in love a chance for redemption.

While Schiller's influence echoes through Ivan's and Alyosha's words as well—though less directly—we'll explore those connections later. For now, what's crucial is understanding that Dostoevsky uses these Schiller references primarily to illuminate his characters' personalities rather than to create hidden literary parallels.

I hope you're enjoying diving into the novel. This week there will be a summary of Book Three and a brief analysis of Part 1 to begin our discussion of the novel's genres and composition. Then we'll continue reading.

I hope you're enjoying diving into the novel. This week there will be a summary of Book Three and a brief analysis of Part 1 to begin our discussion of the novel's genres and composition. Then we'll continue reading.

I am so thankful for this contemplative and informative walkthrough. You are just doing a really lovely job!

Again, As I felt with C&P, I feel the need to print out all your essays and reread this book with them beside me. It is hard for me to see all these underlying themes as I have strong negative reactions to everyone’s absurd, to the point of unbelievable, behavior. I went back to read the very beginning and was thoroughly surprised. The “author” states that Aleksey was his hero, but not a great man, “ a vague and undefined protagonist.” Hmm?