Dostoevsky's Tobacco: The Story of a Harmful Habit

Smoking is harmful to your health! Dostoevsky's life serves as a stark example of how smoking can be lethal

Greetings to all Dostoevsky enthusiasts!

A few days ago marked the anniversary of Dostoevsky's death, and today we tell the story of its causes and consequences. About that very harmful habit of the writer which, alas, shortened his years of life.

144 years ago, Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky died suddenly—February 9th by the modern calendar, though January 28th is inscribed on his gravestone.

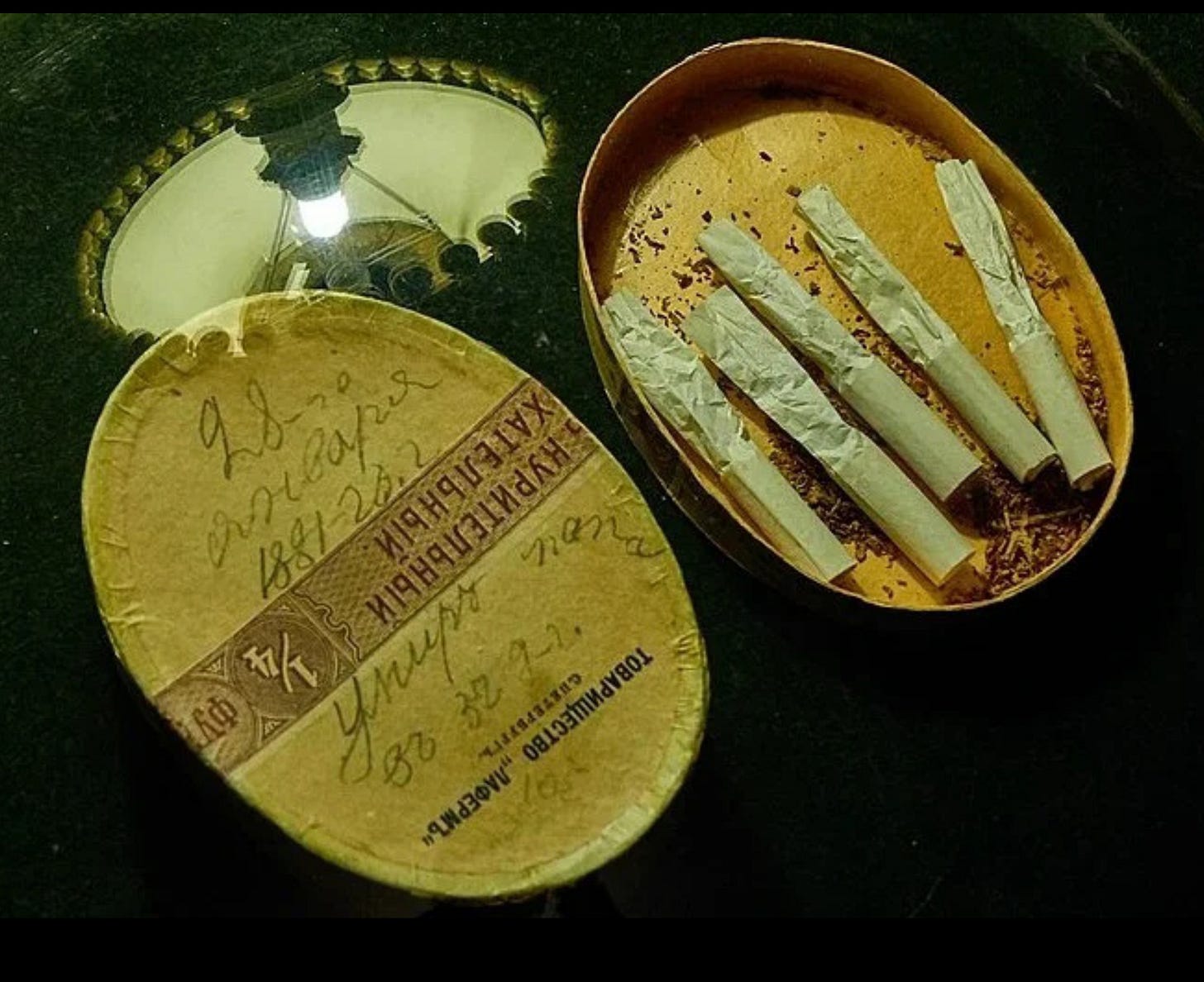

Cigarettes were his constant companion until death. In the Dostoevsky Museum in Petersburg, there remains a poignant artifact: a box of smoking tobacco bearing an inscription from his eleven-year-old daughter Lyuba:

"January 28, 1881 - Papa died."

Memories of his smoking habit

Fyodor Mikhailovich was an inveterate smoker. Cigarettes were his constant companion and a source of creative inspiration. His wife Anna mentioned this in her "Diary," noting how she first observed this habit when she came to the writer's apartment to take dictation:

I sat by the wall at a small table, while Dostoevsky would alternate between sitting at his desk and pacing around the room smoking, frequently putting out one cigarette and lighting another. He offered me a cigarette too. I declined.

"Perhaps you're refusing out of politeness?" — he said.

I hastened to assure him that not only did I not smoke, but I didn't even like seeing ladies smoke.

Despite his constant financial struggles, the writer maintained a passion for quality goods. He purchased premium paper and expensive chocolate. For cigarettes, he favored those from the Saatchi and Mangubi or Laferme factories—both among the finest manufacturers of their time, as proven by their numerous European awards. These prestigious establishments served as official suppliers to the Imperial Court, and it was their tobacco that Fyodor Mikhailovich cherished.

The writer preferred to roll his own cigarettes. Therefore, on his large desk in his study, alongside a stack of paper and a pen, stood a box of tobacco and a container with paper tubes and cotton. According to Anna Grigorievna, he would fill them "...mixing two varieties: Saatchi and Mangubi Dives medium blend with Laferme, using a quarter pound at 80 kopeks."

She also provides an interesting and little-known fact:

After his trip to Moscow for the Pushkin celebration, he gave up cigarettes and smoked cigars, claiming that he coughed much less now. The cigars were good, expensive ones, 25 pieces for 6 rubles and more.

The writer's great-grandson, Dmitry Andreyevich Dostoevsky, shared family knowledge in an interview. According to Anna, the writer's wife, even the children took part in the tobacco ritual. Fyodor Mikhailovich taught them to mix two types of tobacco in precise proportions. The children enjoyed this process and would fill the cigarettes themselves—unwittingly preparing what we now know was poison for their father.

Despite this legacy, Dmitry Andreyevich participated in promoting cigarettes (2023) named "Dostoevsky" in honor of his great-grandfather, even while acknowledging they led to his demise.

“He smoked - he always smoked a great deal - and I can still see his pale and thin hand, with knotted fingers and an indented line around the wrist - perhaps traces of prison shackles - I can see how this hand extinguishes a thick, finished cigarette, and the sardine tin on top filled with the butts of his 'cannons'.”

This is how Varvara Timofeyeva, a proofreader at the printing house of "The Citizen" journal where Dostoevsky worked, remembered him

The Writer's Brother and the Tobacco Factory

Few people know that Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky's elder brother was also a literary figure, translating Schiller's poems, Goethe, and Victor Hugo's novels into Russian. But his interests extended beyond literature—he was also deeply involved in the tobacco business.

In the 1850s and 1860s, he ran a tobacco enterprise in St. Petersburg. Mikhail Dostoevsky's factory was located in the same district where Dostoevsky would later place Raskolnikov's room. Mikhail Mikhailovich's apartment occupied the third floor of the building, while the tobacco factory, warehouse, and shop operated on the ground floor. Fyodor Mikhailovich himself lived in this same building from 1861 to 1863.

It's unclear what inspired the writer to venture into the tobacco business in 1852. Yet he devised an ingenious marketing strategy: including a surprise gift in each box of 250 cigarettes. These gifts, which he bulk-ordered from Paris, London, and German cities, proved highly successful—customers eagerly purchased the boxes since the gifts' value often exceeded that of the cigarettes themselves.

Dostoevsky maintained high standards for his products but, sadly, not for his health. The writer and manufacturer Mikhail Mikhailovich died at just 43 in 1864. His death certificate cited "bile in the brain"—an obscure medical condition (I don't know what that disease is called)—rather than smoking as the cause.

Neither his literary works nor his tobacco business brought financial prosperity. Instead, he left substantial debts upon his death. The burden of these financial obligations, along with the care of his large family, fell to his brother Fyodor Mikhailovich, who spent 13 years paying off the debts with interest.

Was the great writer aware that smoking was damaging his health?

Yes, he knew this. He often wrote himself that it was a harmful habit. But let me also share a story from "A Writer's Diary".

"A gentleman suddenly entered the train car, a perfect gentleman, very much resembling the type of Russian gentlemen who wander abroad. He entered leading his little son, a boy of about eight years old, if not less. The boy was charmingly dressed in the most fashionable European children's outfit, with a lovely jacket, elegantly shod, with batiste undergarments. The father, evidently, took good care of him.

Suddenly, as soon as they sat down, the boy says to his father: 'Papa, give me a cigarette?'

The father immediately reaches into his pocket, takes out a mother-of-pearl cigarette case, removes two cigarettes, one for himself and another for the boy, and both, with the most ordinary manner that clearly showed this was a long-established habit between them, light up. The gentleman sinks into some thought, while the boy looks out the train window, smoking and inhaling.

He finished his cigarette very quickly, then, not even a quarter hour later, suddenly again: 'Papa, give me a cigarette?' - and again both light up, and during the two stations they sat with me in the same car, the boy smoked at least four cigarettes.

I had never seen anything like it and was very surprised. The weak, delicate, completely undeveloped chest of such a small child was already accustomed to such horror. And how could such an unnaturally early habit develop? Of course, by watching his father: children are so imitative; but how could a father expose his infant to such poison? Consumption, respiratory catarrh, cavities in the lungs - this is what inevitably awaits the unfortunate boy, there are nine chances out of ten, it's clear, it's common knowledge, and it's the father himself who cultivates this unnaturally premature habit in his infant! What this gentleman wanted to prove - I cannot even imagine: was it contempt for prejudices, or to advance a new idea that everything previously forbidden is nonsense, and on the contrary, everything is permitted? - I cannot understand. This case remained inexplicable to me, almost miraculous. Never in my life had I met such a father and probably never will. What remarkable fathers one encounters in our time!"

There is no doubt that Fyodor Dostoevsky knew about the risks associated with smoking. He knew, but continued to smoke heavily.

Death and Funeral

Fyodor Dostoevsky outlived his elder brother who died at 43. Though Dostoevsky lived another 16 years, tobacco ultimately played a role in his death. He died of pulmonary emphysema—a disease most commonly caused by smoking.

The illness developed gradually, manifesting as frequent colds and shortness of breath. He pursued various treatments: compressed air therapy in Russia and healing waters in Germany. While these brought temporary relief, the disease continued to worsen. His condition was further complicated by bronchial asthma. Though doctors warned him against emotional stress, physical exertion, and smoking, he never gave up his tobacco habit.

At 8:40 in the evening on January 28 (February 9), 1881, Dostoevsky suffered severe throat bleeding and passed away. A priest was present to administer the last rites.

The funeral procession on January 31 carried his body to the Alexander Nevsky Lavra church. A large crowd accompanied the procession as it made its way along Nevsky Prospect, the journey taking two hours to cover several kilometers.

Mourning cards bearing Dostoevsky's signature facsimile and the dates of his life were distributed at both the beginning and end of the procession.

"It was a beautiful idea: it was as if the deceased writer himself was thanking us for attending and sending his autograph as a memento" — wrote Tyumenev, one of the participants.

Anna Dostoevskaya noted with great amazement in her memoirs that after the funeral service for the great novelist, not a single cigarette butt was found on the floor of the Alexander Nevsky Lavra Cathedral. For the lengthy church services of that time, this was quite remarkable...

But for a long time he was also addicted to gambling, which he only quit 24.4.1871 after he lost his last Taler at the casino in Wiesbaden. He wrote to his wife Anna that he will never again set a foot into a casino because has become „a new person“:

„Anja, my guardian angel! Great things have happened to me. Gone is the vile delusion (fantazija) that tormented me for almost ten years. For ten years (more precisely since the death of my brother, when I was suddenly crushed by debt) I constantly dreamt of winning at the game. I dreamed about it seriously and passionately. But now that's all over. This was FINALLY the last time. Believe me Anja, my hands are free now. The game tied my hands. I was captivated by the game. But now I will think about work and no longer spend nights dreaming about the game like I used to. And as a result, the work will also progress faster and better, and God will bless it.“ (letter to Anna. Dating from the 29th of April 1871).

By the way: the meaning of the English word „addiction“ has changed of the last centuries - from

„To speak to,’ its earliest meaning, is explained by legal and augural technical usage (5th cent. BCE). As addicere and addictus evolved in the Middle and Late Roman Republic, the notion of enslavement, a secondary derivation from its legal usage, persisted as descriptive and no longer literal. In the Early Modern period, the verb addict meant simply ‘to attach.’ The object of that attachment could be good or bad, imposed or freely chosen. By the 17th century, addiction was mostly positive in the sense of devoting oneself to another person, cause or pursuit. We found no evidence for an early medical model. Conclusion: Gambling appears to be the only behavior that could satisfy both original uses; it had a strongly positive meaning (its association with divination), and an equally negative, stigmatizing one. Historically, addiction is an auto-antonym, a word with opposite, conflicting meanings. Recent applications are not a corruption of the word but are rooted in earliest usage.“ see https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/16066359.2018.1543412#abstract

Thanks for this bitter-sweet excursion into Dostoevsky‘s smoking habits. He was not only addicted to tobacco but also for a long period of his life a gambler