Dostoevsky constantly drank tea...

About the tea traditions in St. Petersburg in the 1860s, about the samovar, and about the 5 ways to drink tea

There were no questions specifically about the novel, only general ones, so I decided to approach them differently. One question - one article. Next time - it will be the question from

about psychiatry, and medicine of Dostoevsky's time, namely, how Dostoevsky himself related to medicine, what was known about psychiatry at that time, and why Zosimov (who is actually a surgeon in Dostoevsky's work!) consulted on Raskolnikov's mental state.I want to talk a bit about the tea tradition of Dostoevsky himself and St. Petersburg in general.

asked this question in the comments, and so I conducted a small investigation to understand how Nastasya drank tea and why. This leads to a conversation about tea culture in the form of a list of brief facts.Dostoevsky's great love for tea

can be inferred from his books. It is also the favorite drink of his characters. Usually, tea appears on the table during calm and - as far as possible in Dostoevsky's novels - comfortable moments.

The main character of his "Notes from Underground" even left a famous phrase in Russian literature: "Should the world go to pot, or should I not have my tea?" («Свету ли провалиться, или вот мне чаю не пить?»)

Dostoevsky's acquaintances in different years recalled how he loved to have long conversations over tea. Mikhail Alexandrov mentioned that Dostoevsky would drink several glasses of very strong and sweet tea. According to Varvara Timofeeva, the proofreader of the "Grazhdanin" magazine, Dostoevsky was so delighted by descriptions of tea drinking in other people's texts that he himself was drawn to the samovar. Anna Dostoevskaya wrote that her husband very much enjoyed brewing and pouring tea himself, and during their foreign travels, they would look for a tea shop in every new city.

I couldn't find photographs of Dostoevsky at the tea table. But there is an alternative - Leo Tolstoy with his family at the tea table!

Where tea was brought to the Russian Empire from

In the the17th century, Chinese ambassadors gifted tea to Mikhail Fyodorovich Romanov (the first tsar of the Romanov dynasty, before them were the Rurikids) which the tsar liked so much that after some time, the first contract was signed to supply this wonderful drink from China. However, due to its high price, tea was only available to city dwellers. You can't fill up on tea, and it's understandable why there wasn't a queue of ordinary peasants lining up for it.

But everything flows, everything changes, and so tea became an integral part of Russian life. Not a single event went without this drink, be it matchmaking or heartfelt Sunday gatherings. In Russia, one could have tea in different ways.

In the 1840s-1850s, tea imports accounted for up to 95% of all Chinese imports to Russia and were valued at 5-6 million rubles per year (for comparison, during the same period, all Russian grain exports yielded 17 million rubles per year). Tea trade was conducted exclusively on a barter basis, in exchange for tea, Russian merchants supplied China with fabrics, processed leather, furs, and metallurgical products.

Let's remember that the novel was written in 1866, and the events take place in 1865.

In the mid-19th century, a pound (450 g) of the simplest Chinese tea cost 2 rubles 50 kopecks (in modern terms, this is approximately 15-20 euros). So, in general, tea became accessible to the majority.

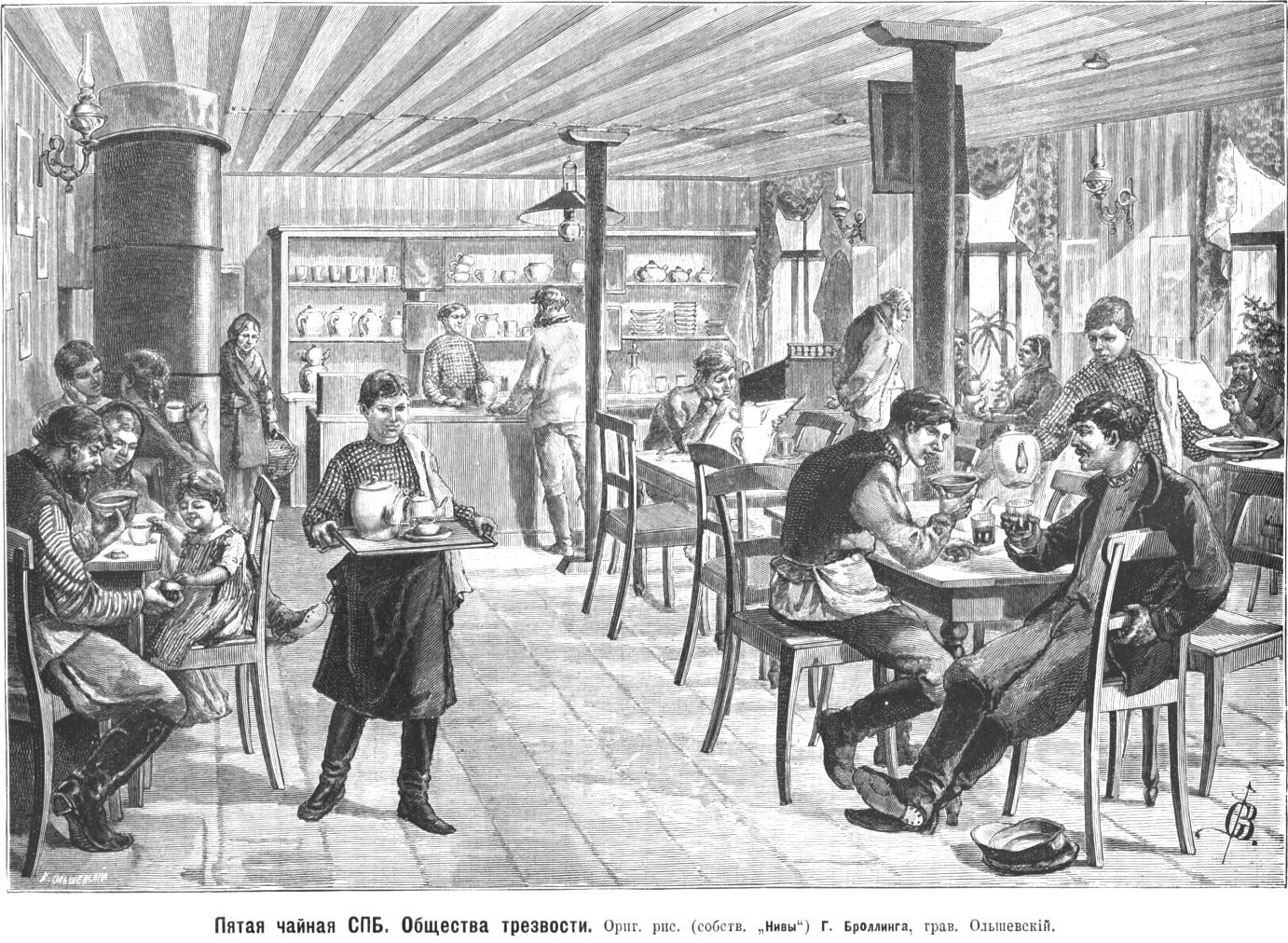

The emergence of tea houses

A special milestone in the history of tea in Russia was the appearance of tea houses during the reign of Alexander II. Such establishments were unique to Russia. Initially, they appeared in the Tver province but quickly spread throughout the country. These establishments had many peculiarities: alcohol was prohibited here, tea was served in two teapots – one contained the brew, the other hot water, and the latter could be refilled for free as much as desired, the tradition of drinking tea with a bite of sugar or as it was then called "with nibbling" came to tea houses from Siberia, music was allowed here, billiards was often played in tea houses, and there were also newspaper stands. Snacks could be ordered for an additional fee.

For obvious reasons, tea houses were also called sobriety houses.

Tea house owners received tax benefits, and rent was extremely low. Initially, tea houses appeared near large industrial enterprises on the outskirts of cities, then they began to open near markets and coachmen stands. It was customary to meet and socialize in tea houses; here one could find solicitors ready to draw up a petition or some other necessary document for a minimal fee.

"Almost next to him at another table sat a student whom he did not know at all and did not remember, and a young officer. They played billiards and began to drink tea." (Chapter 1.6)

Perhaps it was in one of these tea houses that Rodion overheard the conversation between two students. This episode mentions billiards and tea, and there is no alcohol, which is uncharacteristic of ordinary beer halls and taverns. This could be an interesting detail, suggesting that the students were speaking with clear heads and that Rodion himself was not actually an alcoholic, since he frequented such establishments.

What might such a detail say about his character and the perception of alcohol in the novel?

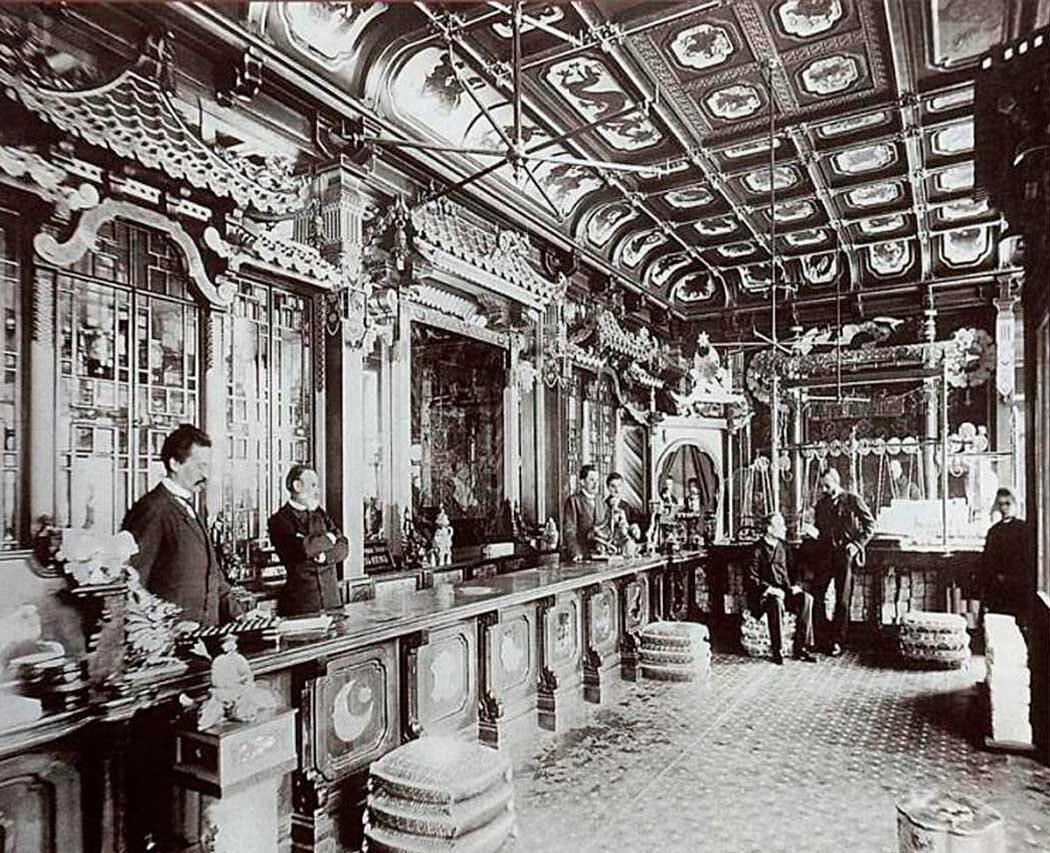

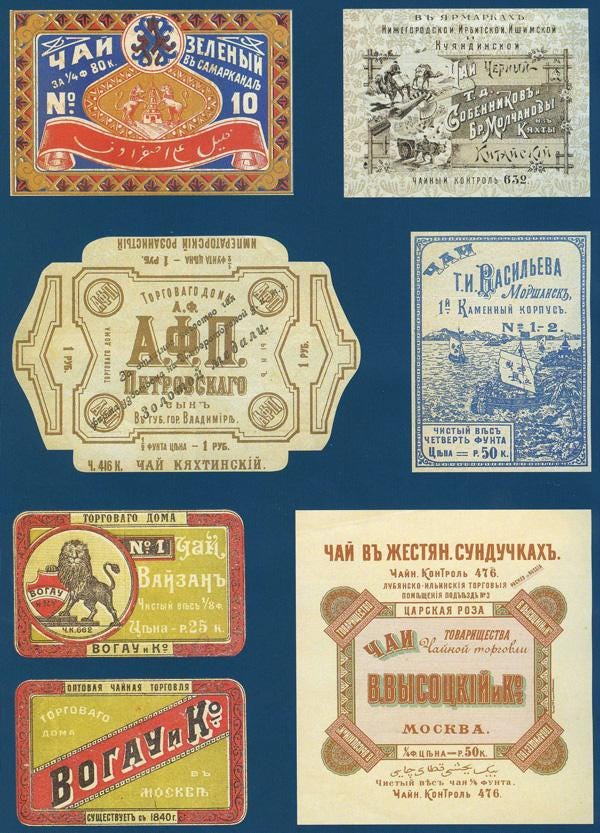

Tea shops

In St. Petersburg until the early 1820s, tea was sold only in the shops of Gostiny Dvor. The first specialized store selling good tea was opened on Nevsky Prospect near the Anichkov Bridge by merchant Belkov.

The photograph shows a tea shop in Moscow in 1875.

Tea was sold in packets, tin boxes, and jars with lavish names: "Rare Khan's", "Golden Khan's", "Khan's Rose", "Khan's High", "Bouquet Rose", "Tsar's Bouquet", "Tsar's Rose", "Indian Rose", etc. The best varieties were sold in glass jars so that the customers could see what they were paying for. Later, instead of luxurious names, teas were assigned numbers in strict accordance with their quality.

The Tea Table

The private detective Masloboev (from the novel "Humiliated and Insulted") lives in comfort, and the novel contains a detailed description of the tea table prepared by his partner, Alexandra Semyonovna.

The tea in this house and everything served with it was of the highest quality.

"A pretty tombac samovar was boiling on a round table covered with a beautiful and expensive tablecloth. The tea set gleamed with crystal, silver, and porcelain. On another table, covered with a different but no less rich tablecloth, there were plates with candies, very good ones, Kiev jams, both liquid and dry, marmalade, pastila, jelly, French preserves, oranges, apples, and three or four kinds of nuts - in short, an entire fruit shop. On a third table, covered with a snow-white tablecloth, stood a variety of appetizers: caviar, cheese, pâté, sausages, smoked ham, fish, and a row of exquisite crystal decanters with vodkas of numerous sorts and most delightful colors - green, ruby, brown, golden. Finally, on a small table to the side, also covered with a white tablecloth, stood two vases of champagne. On the table in front of the sofa were three bottles: Sauternes, Lafite, and cognac - bottles from Eliseyev's and extremely expensive."

Samovar

On the first table in Masloboev's apartment, awaiting the guest, stood a Tula samovar made of tombac (an alloy of 85-90% copper and 10-15% zinc). Tombac samovars were beautiful but expensive, and therefore were found in the homes of well-off people. At the time when the novel was written, a tombac samovar cost, depending on the finish, 25-30 rubles, which was expensive.

The samovar advertisement shows the type and price depending on the volume in glasses and the material it's made of. For example, this type of samovar, the "oval-polished" style, cost from 22 rubles 75 kopecks (for a capacity of 21-23 glasses made of the most basic metal). In the second column are prices for the nickel-plated version, and in the third - those made of tombac.

First and foremost: tea is never brewed in a samovar! Under no circumstances. The rotund "self-heater" is used only for boiling water, and for everything else, there are special teapots: porcelain, ceramic, or metal.

At the top of the samovar is a burner - a beautiful, often openwork "crown" that tops the entire structure. It plays an important role in preparing strong and flavorful tea: a teapot is placed on the burner so that the steam coming from inside warms it and ensures the gradual release of the tea's flavor and aroma.

The tea set

The tea set, which "gleamed with crystal, silver, and porcelain" next to the tombac samovar, referred to a set of dishes for drinking tea. In China, from where this name came to Russia along with tea itself, a tea set could include up to 24 items, starting from a brazier and ending with a bamboo cabinet for storing things.

In Russia of Dostoevsky's time, a tea set referred to a set of dishes consisting of

a teapot for brewing tea,

a cup with a saucer,

a sugar bowl,

and a milk jug.

In poor homes, they made do with just a teapot and a cup, while in wealthy homes, the tea set, which was called a tea service, could also include a tea caddy, dessert plates, vases, small bowls, and saucers made of porcelain, crystal or silver, the indispensable silver teaspoons, a tea strainer, and sugar tongs.

In the taverns of that time, tea was drunk in "pairs". One tea pair consisted of two teapots: a large one with boiling water and a small one with brewed tea, and two or three pieces of sugar. The other tea pair was a cup with a saucer.

At the end of the 1860s in Russia, first in taverns and then at home, people began to drink tea not from cups, but from glasses, which were produced in large quantities at that time and sold at a low price compared to tea pairs. The fashion of drinking tea from crystal glasses, which were placed in silver holders, penetrated even into wealthy aristocratic homes, but didn't last long there. Cheap glass tumblers for drinking tea firmly established themselves only in tea houses, taverns, homes of petty bourgeois, lower-ranking officials, and the diverse liberal and democratic intelligentsia.

Tea in a glass with a holder. To this day, tea is served in such a glass with holders on Russian railways.

According to A. G. Dostoevskaya, Fyodor Mikhailovich himself

"loved white pastila, always bought honey during fasting, Kiev jam, chocolate (for the children), blue raisins, grapes, red and white pastila sticks, marmalade, and also fruit jellies".

Tea from used tea leaves

In “Crime and Punishement” Nastasya (this is the housekeeper who works for Raskolnikov's landlady and brings him food) serves Rodion tea made from used tea leaves several times, i.e., the tea leaves were steeped in boiling water not for the first time. Most likely, these were the used tea leaves from the landlady or other paying tenants. However, in those times, used tea leaves were collected in taverns and other catering establishments, often extracted directly from garbage pits, cleaned of obvious impurities, moistened with dyes, burnt sugar, and chemicals that gave the tea leaves a natural appearance after drying. And such "counterfeit" tea could be sold again.

Sugar

In the 19th century, sugar was served ONLY in the form of a "sugar loaf". It was sold as a whole loaf for well-to-do city dwellers, and shops could also sell it by weight in pieces cut from this loaf. Breaking off pieces from it was not always easy, so people often got injured and there were even cases of sugar being sold with blood (from those who had cut themselves while breaking off a piece).

Ways to drink tea

With sugar dissolved («внакладку»/ vnakladku). This is where the adverb "nakladno" (meaning very expensive) came from. After all, sugar was a very expensive product in Russia. Therefore, only wealthy city dwellers could afford this way of drinking tea. They would drop a piece of sugar into a glass of tea, stir it and drink. It was wasteful, in a word. After all, the tea "would lose both its taste and aroma". However, this method of drinking tea still caught on and is actively used to this day.

With a snack (“С прикуской”). Simply drinking tea is not interesting, especially for children. Therefore, there was always a piece of sweet pie, a stray candy, or bagels to go with the tea.

Sucking on sugar (“Вприкуску” / vprikusku). As we have already said, sugar was too expensive a product. So people stretched it out as much as they could. Sugar at that time was unrefined and in terms of hardness, it was more like a stone. Therefore, sugar tongs were placed in the sugar bowl so that one could bite off a little sugar for tea drinking. A small piece of lump sugar was placed in the mouth and a sip of tea was taken. It melted very slowly, even in hot water. One piece could be enough for 2-3 glasses of tea. And virtuosos who skillfully clamped the sugar between their teeth and drew tea through it, which washed over the "stone" piece of sugar and left a sweet but not cloying aftertaste in the mouth, managed to drink up to twelve cups this way!

This is exactly how Nastasya from the novel drank her tea. But she also drank tea from the saucer, so that it would not be too hot and would cool down quickly - this way the sugar melted even more slowly.

“We must get Pashenka to send up some raspberry jam today, to make him a drink,’ said Razumikhin, sitting back down on his chair and returning to his soup and beer.

‘And where’s she going to find raspberries for you?’ asked Nastasia, balancing her saucer on five outstretched fingers while she sucked up her tea through a sugar lump.”

In pursuit (“вдогонку”/ vdogonku). The poorer people drank tea "in pursuit". They would place a piece of sugar on bread, then gradually bite the bread, pushing the sugar further and further back with their lips. When the bread was finished, the remaining piece of sugar was either set aside for next time or eaten and washed down with tea. The final journey of the sugar piece directly depended on the degree of the peasant's poverty. In other words, they only slightly touched the sugar with their lips and its traces on the bread.

St. Petersburg style. By the way, the St. Petersburg custom of adding rum or cognac to tea, with rare exceptions, never caught on in Moscow, whose residents preferred to enjoy the taste and aroma of these drinks separately.

Fyodor Mikhailovich himself, according to A. G. Dostoevskaya, "loved strong tea, almost like beer... But he especially loved tea at night while working".

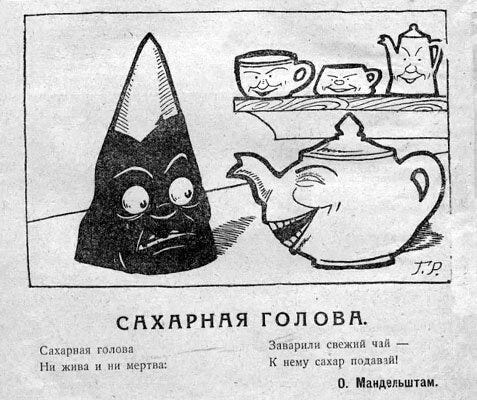

Illustration of tea drinking and a poem by Osip Mandelstam (a famous Russian Silver Age poet). Literal translation of the poem “Sugar loaf “:

Sugar loaf

Neither alive nor dead:

Fresh tea is brewed —

Serve sugar with it!

Do you like to drink tea? Which method do you choose and do you have any tea traditions?

This was an interesting read for me! I especially enjoyed reading about the different ways of drinking the tea. I can't imagine the amount of research it would've taken you to do this piece. Love love it!

During the pandemic, I developed my own ritual with my grandmother's beautiful tea cup. First thing, I would put on a very nice dress. Then when the coffee was ready, I would sit looking out the window, slowly pouring the hot brew and warmed half and half into the elegant porcelain. Starting the day this way set the tone for the rest of the hours. There are not many nice memories of the pandemic, but this teacup ritual is one for me.