Book 2 «An Unseemly Encounter» — Summary Insights, Questions

Chapter by chapter, we witness how scandal builds, finally erupting with full force at the end.

Dear Dostoevsky enthusiasts!

As we prepare to begin the third book of The Brothers Karamazov, let's review the key events of Book Two. This summary provides a chapter-by-chapter breakdown, including plot summaries, main character developments, and the most thought-provoking discussion points from our conversations. While I've selected some insightful comments per chapter, space constraints prevent including every valuable contribution. I encourage you to explore the full comment threads for any chapter that catches your interest—you'll find numerous profound insights throughout.

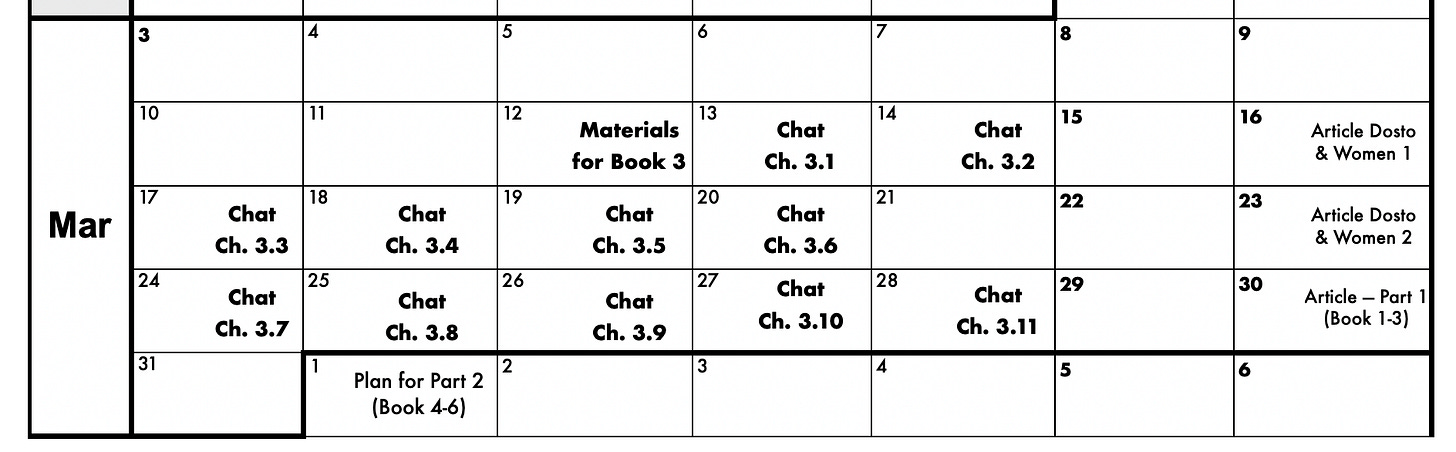

Schedule for the third book:

This is a long piece since the part has 8 chapters, so for comfortable reading please switch to the web version.

CHAPTER 2.1 — They arrive at the monastery

Let's begin with the arrival at the monastery. A meeting has been arranged between Fyodor Pavlovich Karamazov and his eldest son Dmitri, who seek reconciliation over an inheritance dispute. The father lives in the estate that belonged to Dmitri's mother, his first wife. Dmitri claims his father has withheld his rightful inheritance payments. Both parties agreed that Elder Zosima's mediation might help the meeting proceed more smoothly.

The party arrives in two carriages: Fyodor Karamazov and his middle son Ivan in one, while Pyotr Miusov and his young relative Pyotr Kalganov occupy the other. Maximov leads them from the monastery to Elder Zosima's skete (hermitage — 2 on map).

Here is the modern layout of the monastery (A) and the skete (B). It shows the approximate path the characters took to the skete. As you can see on the diagram, there are even small graves that Miusov keeps glancing at.

Some points that we discussed:

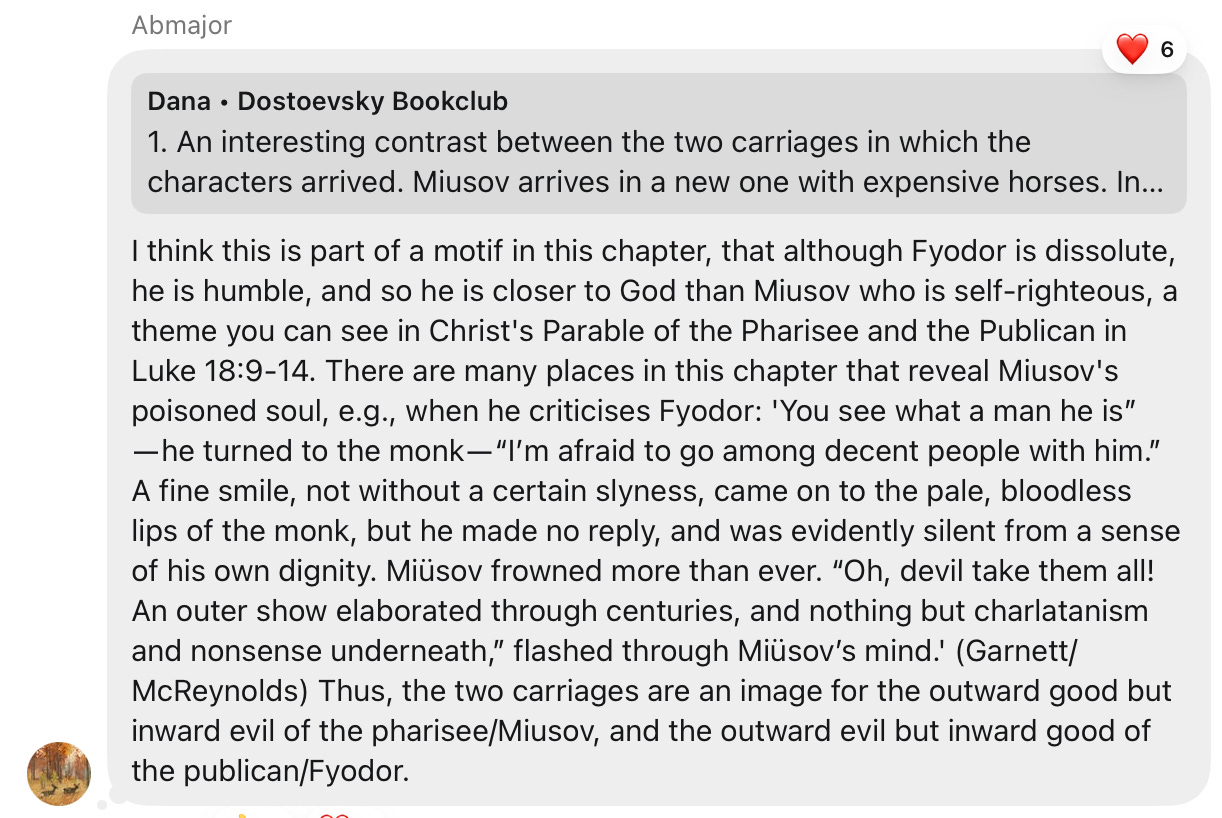

An interesting contrast between the two carriages in which the characters arrived. Miusov arrives in a new one with expensive horses. In the second one - decrepit with old horses - come the Karamazovs. What do you think about this contrast? Why does Karamazov, with all his money, have everything falling apart?

What do you think about Maximov's character? Karamazov calls him von Sohn. This refers to a real victim of a notorious criminal case in Petersburg. I wrote a separate article about this murder.

Maximov refers to Elder Zosima as "un chevalier parfait". This is a reference to one of Zosima's possible prototypes - Saint Francis of Assisi. I published an article about the prototypes.

Before the gates of the skete, Karamazov desperately and even defiantly crosses himself to all the saints depicted there (1 - on map). How did you perceive his behavior? How sincere is his faith? This is very similar to his "theatrical scene" when he learned about the death of Adelaide - his first wife.

Also interesting is the new character Kalganov, who doesn't say anything yet and mostly appears embarrassed. His role in this meeting is still unclear - why did Miusov bring him along?

Link to our discussion of this chapter.

Some comments of

&CHAPTER 2.2 — The Old Buffoon

Noon. In it, the long-awaited meeting finally begins, or rather, should begin. Everyone except Dmitri Karamazov has gathered at Elder Zosima's. And the characters don't waste time: they cannot wait calmly, but truly start behaving like old buffoons. And I'm not just talking about Fyodor Karamazov here. Miusov also behaves like an idiot. In the end, Zosima decides not to waste time on this waiting and goes to attend to his other visitors for a while.

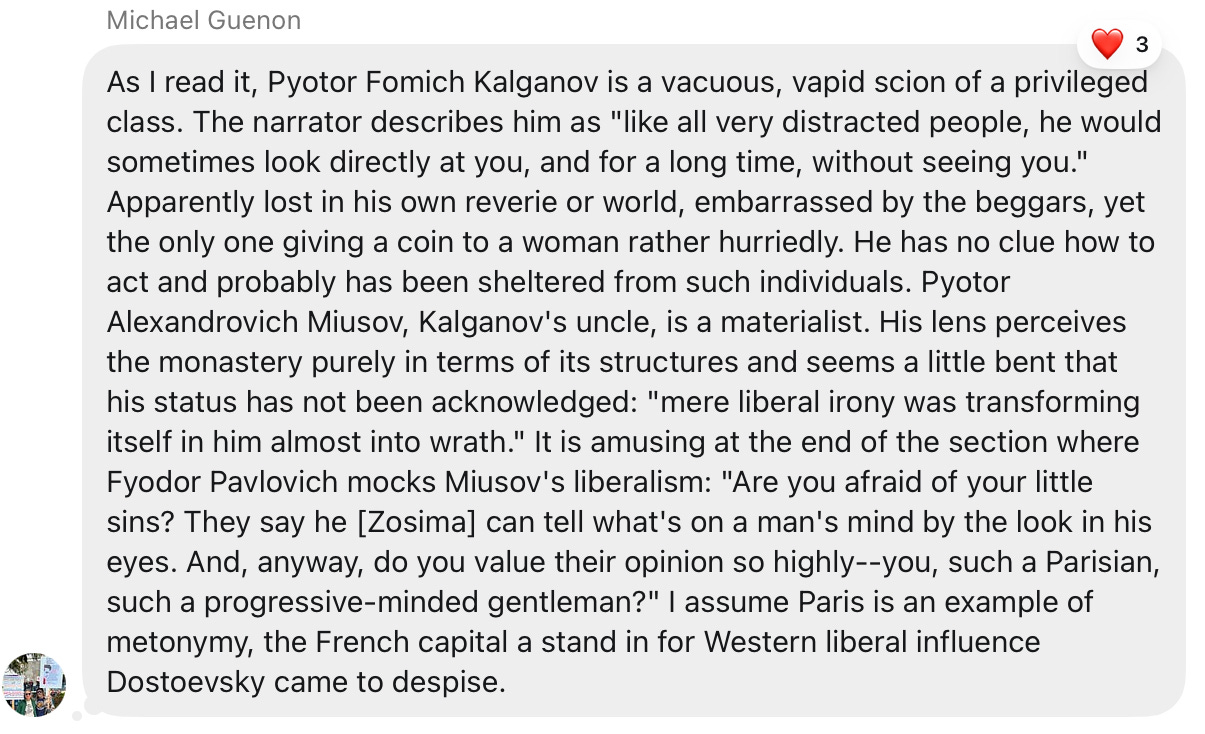

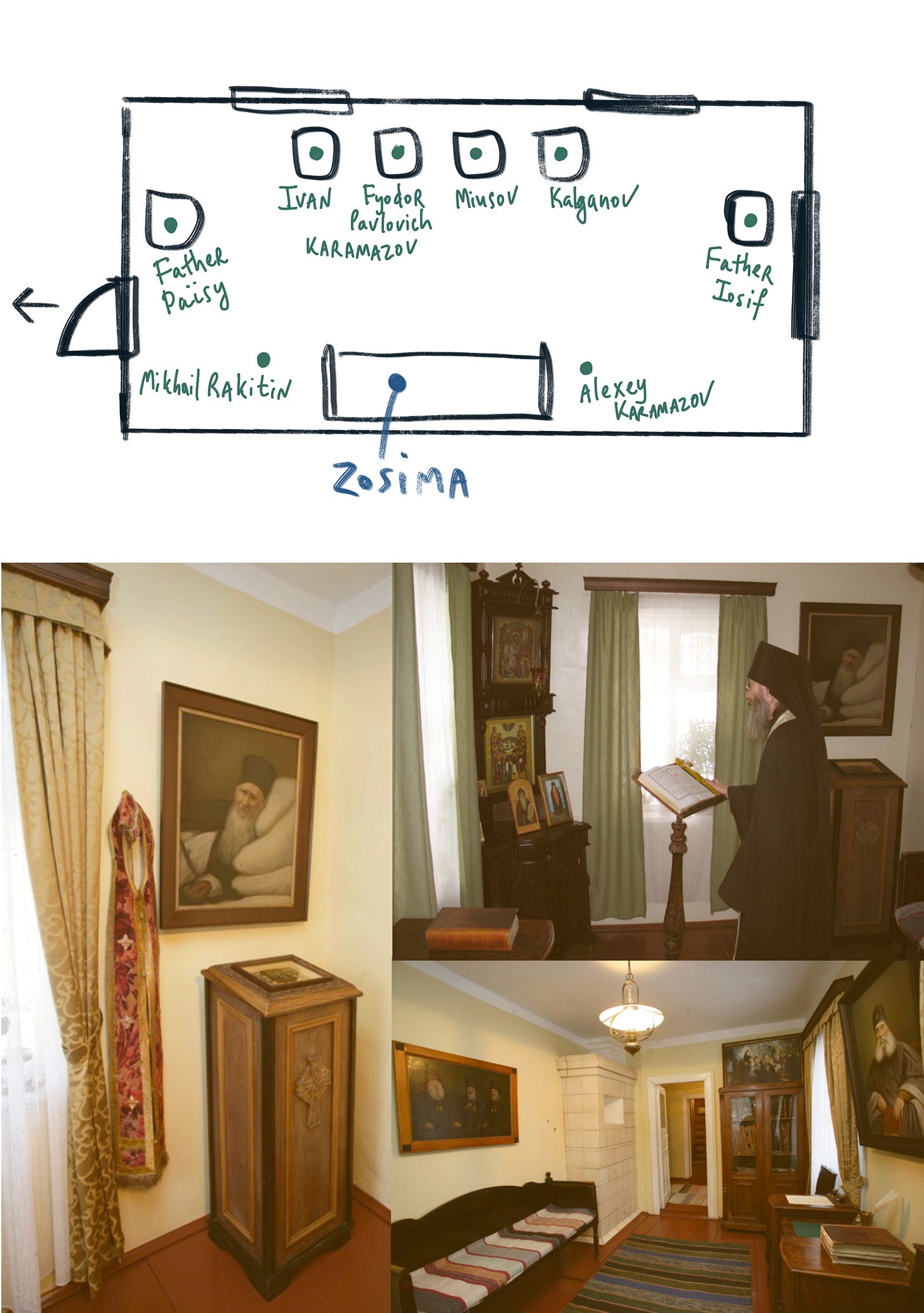

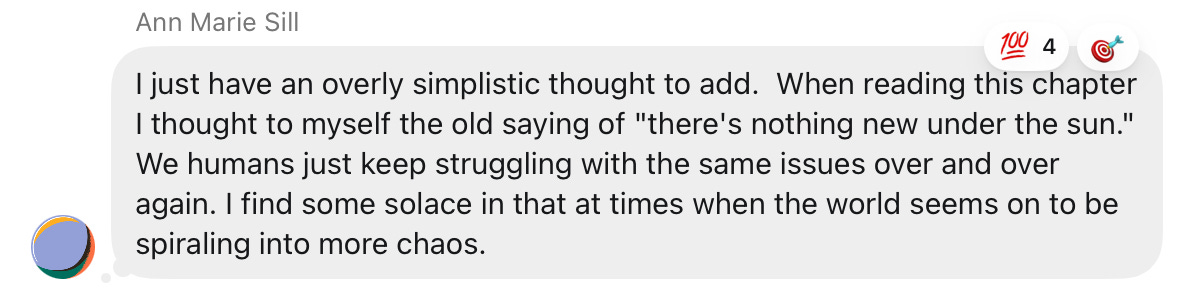

I've sketched out how the guests were likely arranged in this chapter for clarity, though they may have been seated differently. I've also included photographs of Elder Amvrosy's cell—which Dostoevsky used as a model for his description in the novel. The photos display the cell as it appears today in its museum state.

Some points that we discussed:

In this chapter, we are given a description of the Elder. That he was disliked. He is old, unattractive, almost bald, and ill. "By all indications, a spiteful and arrogant little soul" - thinks Miusov. Why is Zosima presented to us this way? Is it to show his physical unattractiveness in contrast with his inner beauty?

What are your thoughts on Fyodor Karamazov's behavior as the central buffoon? He continuously spins one ridiculous tale after another, fabricating stories at will. What drives this behavior—a desperate need for attention, deep discomfort, genuine pleasure in self-mockery, or something else entirely? And how do you interpret the stories themselves?

The narrator notes that such outrageous behavior from Miusov and Karamazov was unprecedented in the Elder's cell. Typically, these chambers witnessed "only love and grace on one side, and repentance and the desire to resolve difficult questions of the soul on the other." Was it Dmitri's delayed arrival that brought this chaos? Or perhaps Miusov and Karamazov were simply unfamiliar with the concepts of repentance and soul-searching?

Shame emerges as a central emotion in this chapter, manifested in various ways. When Zosima says "Don't be ashamed of yourself, for everything stems from that," it creates an interesting contrast with Alexei's immediate shame over his relatives' "incorrect" greeting of Zosima. While Zosima remains emotionally detached from these antics—seeing beyond the superficial awkwardness and misplaced conversations—Alexei has not yet reached this level of understanding. He remains deeply ashamed of his father's behavior. This raises an important question: is shame a constructive or destructive emotion?

An interesting nuance often lost in translations: Fyodor Pavlovich pronounces Diderot, carefully enunciating each letter (Дидерот), rather than the correct French pronunciation "Didro" (Дидро), which should be without the final T. This is curious because we know he speaks French—he's quoted it before. Zosima then mirrors this pronunciation. No one ever pronounced Diderot's name this way like Karamazov, who affects the manner of an uneducated person—though ironically, a truly uneducated person wouldn't know Diderot at all.

Link to our discussion of this chapter.

Comment of

a andCHAPTER 2.3 — Devout Peasant Woman

In this chapter, Zosima briefly leaves the gathered Karamazovs to spend ten minutes meeting with parishioners who await him. Since women are not permitted on monastery grounds, they wait in the outer gallery for his counsel. We will witness Zosima's interactions with four women, each bringing her own unique story and request.

About the chapter title "Devout Peasant Woman" (Верующие бабы)

The author uses "baba" (баба) rather than the neutral word "women" (женщина). For modern women, being called "baba" can be offensive, as it's now used to refer to older, often unattractive women. It's also a shortened form of "babushka" (grandmother), used by grandchildren as a term of endearment.

In ancient Slavic culture, however, "baba" derives from "ba"—meaning "to be" or "to live"—and signifies "gates of life." The term specifically referred to women who had given birth to daughters, creating an unbroken cycle of life-giving potential. This reverent meaning explains why "baba" evolved into the cherished word "babushka" (grandmother), a figure universally beloved in Slavic families.

Some points that we discussed:

At the beginning of the chapter, the narrator shares childhood memories of witnessing "klikushas" (shrieking women) and how "unclean spirits" would supposedly leave them. A klikusha suffered from a specific psychological condition characterized by seizures, screaming fits, and erratic behavior. Across different cultures, such women were believed to be possessed by demons—a phenomenon observed worldwide. This condition specifically affected women who had given birth and was often connected to difficult childbirth, depression, and abuse from cruel husbands. Karamazov's second wife Sofia became a klikusha—evidently due to his mistreatment. Whether the traditional treatments like exorcism and rituals helped through placebo effect, self-suggestion, or simply because these women finally received compassionate attention remains unclear. Elder Zosima, who often encountered klikushas, demonstrated a particular ability to help them.

The first woman's story tells of a mother grieving for her dead son Alexei. This directly mirrors Dostoevsky's own biography and his conversation with Elder Ambrose. Zosima's reference to the deceased as "Alexei, son of God" creates a meaningful parallel with Karamazov, who shares this name. The "son of God" designation carries special significance for Alexei Karamazov's character. In the previous chapter, this parallel was made even more striking when Fyodor Pavlovich Karamazov alluded to himself as Satan by calling himself the "father of lies." At the end of the article about the monastery, I wrote about Dostoevsky's meeting with Elder Ambrose.

The second story concerns a mother who requests prayers for her son's soul. Her son, a military man, hasn't contacted her in a long time. What's striking is Zosima's unwavering confidence that her son lives, despite his own military background. As a former soldier, he should understand the constant presence of death in military life, especially given the perpetual state of warfare somewhere in the world. Yet he assures her with complete certainty that her son is alive.

The third story concerns a woman who killed her abusive husband. Zosima consoles her with the message that God can forgive any sin, and that through love, all sins may be redeemed—even suggesting that one person's love can help redeem another's sins. What are your thoughts on this?

The fourth woman came simply to check on Zosima's wellbeing. While yesterday's chapter revealed a closed circle of lies and shame, today we witness a circle of care and love. Despite her own poverty, she donated 60 kopeks for someone else in need. This beautifully illustrates how Zosima not only provides comfort and peace but participates in this circle of compassion—people come to him with genuine concern for his welfare, and these exchanges of care nourish his spirit as well.

Link to our discussion of this chapter.

Comment of @Hissan and

Chapter 2.4 — Lady of Little Faith

In this chapter, we meet Mrs. Khokhlakova and her wheelchair-bound daughter Liza (Lise). Though previously mentioned, they now appear in person before Elder Zosima. They deliver a letter to Alyosha from Katerina Ivanovna—a mysterious woman yet unknown to us—requesting his presence regarding matters concerning his brother Dmitri.

While Mrs. Khokhlakova grapples with her crisis of faith, Liza reveals that Alexei was once her caretaker, establishing their prior connection. Mrs. Khokhlakova, it seems, knows Alexei's former guardian, Efim Polenov. When Liza wishes to rekindle her friendship with Alexei through a visit, Zosima readily gives his blessing.

Some points that we discussed:

What are your thoughts on Khokhlakova? At just 33 years old, she has been a widow for some time. Despite her youth, she has faced considerable hardships. She travels a great distance with her daughter Lise to seek the elder's healing and counsel. What makes the narrator describe her as having "little faith"? In what ways does she contrast with the devout women we encountered in the previous chapter?

Khokhlakova shares Fyodor Pavlovich Karamazov's existential concerns about death. While Fyodor obsesses over hooks in hell and its arrangement, Khokhlakova dreads the possibility of nothingness after death—merely emptiness and a burdock growing on her grave. Both characters appear more fixated on the afterlife than on living in the present. Elder Zosima offers them similar counsel: to cease their self-deception. Through these parallels, the themes of self-deception and death anxiety emerge.

The burdock on the grave. The burdock mentioned by Khokhlakova is a quote from Turgenev's novel Fathers and Sons. This is what the character Bazarov, Russian literature's chief nihilist, says:

"And I've come to hate that last peasant, Philip or Sidor, for whom I must toil and who won't even thank me... and what do I need his thanks for? Well, he'll live in a white cottage, while a burdock will grow from my grave; well, what then?"

So it's interesting that the reference to the burdock on the grave is borrowed from this particular character. A burdock is not like flowers on a grave that are associated with the continuation of life. It's a weed, often found on abandoned, untended graves. Although burdock is used for medicinal purposes, like tinctures, it's still a weed. Do you think Khokhlakova is a nihilist?

Consider the paradox of those who claim to "love all humanity but hate every individual person." Elder Zosima recalls someone expressing this sentiment, and he sees similar thinking in Madame Khokhlakova's reflections. While a crowd differs fundamentally from individual personalities, some people experience the opposite—they love individuals but despise humanity as a collective. This raises an intriguing question: can we truly separate our view of humanity from our treatment of individual people?

Link to our discussion of this chapter.

Comments of

andChapter 2.5 — "Amen, amen!"

This is the first truly complex chapter in the novel, containing fewer plot events but rich discussions and debates about Ivan Karamazov's article.

In the original, the title is “Буди, буди” (stress on the first syllable). This is the Church Slavonic equivalent of Amen, or "so be it".

The scene continues in Zosima's chamber, where the group awaits Dmitri's arrival. This waiting period proves valuable as those present engage in profound discussions about pressing matters. Through their debate about church-state relations, the novel's central theme of Repentance emerges. The discussion weaves together various philosophical movements: Slavophilism, social Christianity, Westernism, pochvennichestvo, and others.

Yet at its heart lies a fundamental question:

How should one atone for sins?

What path leads to true repentance, and is forgiveness truly possible?

The discussion is challenging to follow for two main reasons. First, it centers on the 1860s reforms — events that occurred 160 years ago. The characters themselves are witnessing these social movements in their early stages, unable to foresee their eventual impact. Secondly, Dostoevsky weaves the arguments of contemporary philosophers, writers, and public figures into his characters' dialogue. This adds complexity through their subjective and sometimes contradictory viewpoints. The author primarily engages with Vladimir Solovyov's ideas presented in "Lectures on Godmanhood." He also explores concepts of "social Christianity" that later formed the basis of his own "Russian socialism," which he detailed in his 1881 "A Writer's Diary." This "Russian socialism," centered on the idea of human brotherhood, shares connections with French "social Christianity."

The main idea of Ivan's article:

The state court punishes the criminal by mechanically cutting them off from society, while the church court sees its purpose as rebirth, resurrection, and salvation of the person. And he examines different combinations of state and church. Ivan Karamazov's article presents two main theses:

The first and main thesis is formulated by Hieromonk Iosif, the librarian: "they completely reject the separation of church and state in matters of ecclesiastical-social court." It should be noted that this thesis stems from that reality, as there was no other relationship between church and state in the Russian Empire. And Ivan contemplates that if it has always been this way, it doesn't mean it cannot be different and that a different approach might even be better and more effective.

The second thesis argues that the historical separation of church and state distorted the original ideal. According to Ivan, the inclusion of the church into the Roman state became a serious deviation from the norm, since the pagan state and Christian church pursue fundamentally different goals.

Some points that we discussed:

Zosima also draws a clear distinction between state and church courts:

"...if Christ's church did not exist today, there would be nothing to restrain the criminal in his wickedness, nor would there be any real punishment afterwards - not the mechanical kind, <...> which in most cases only irritates the heart, but real punishment, the only effective one, the only frightening and pacifying one, which lies in the awareness of one's own conscience."

Further, the elder points to the connection between Rome - Catholicism and the state, which is fundamentally a pagan institution: "In Rome, for a thousand years now, the state has been proclaimed in place of the Church. Therefore, the criminal no longer recognizes himself as a member of the Church and, being excommunicated, remains in despair. And if he returns to society, it is often with such hatred that society itself seems to excommunicate him." Thus, Zosima's words reveal the difference between Catholic and Orthodox understanding of punishment as a form of repentance.

In place of Zosima's concept of "active love" comes here the idea of "active punishment," from which "the church, as a tender and loving mother [...] withdraws". However, it is precisely this "active punishment" that, in his opinion, catches up with "the foreign criminal," who "they say, rarely repents, because even the most modern teachings confirm him in the thought that his crime is not a crime at all, but merely a rebellion against unjustly oppressive force.

Rather than delving deep into old philosophy, let's focus on one key question: how should society deal with those who commit crimes? Should we follow the state's approach — isolating offenders in prisons, cutting them off from society, with little regard for their inner lives? Or should we consider the church's perspective — seeking to transform individuals through repentance and spiritual rehabilitation? While I'm uncertain how the church could effectively implement such rehabilitation without prisons, I welcome any historical examples or creative suggestions you might have.

Link to our discussion of this chapter.

Comments of

& &Chapter 2.6 — "A MAN LIKE HIM DOESN'T DESERVE TO LIVE!

As Book 2 nears its end, Dmitri finally makes his appearance. In the monk's cell, the debate about Ivan's article on Church-State separation continues. Dmitri's arrival instantly shifts the room's atmosphere. Fyodor Pavlovich launches into a heated argument with his son, revealing that their conflict extends beyond money to include rivalries over women. The tense exchanges continue until Elder Zosima makes a "strange" bow at Dmitri's feet, shocking everyone present. This gesture brings the meeting to an abrupt end. The group disperses—some return home, while Miusov and Ivan accept a monastery monk's invitation to dine.

The approximate seating arrangement of all meeting participants. Dmitri went to the window and sat in a chair next to Father Paisy.

Some points that we discussed:

The chapter's title comes from Dmitri's exclamation about his father: "Why should such a man live!" (Зачем живет такой человек!). Avsey's translation—"A Man like him doesn't deserve to live!"—takes a more extreme interpretation than the original Russian. Dmitri is questioning the purpose of his father's existence rather than making a judgment about whether he deserves to live. But Fyodor Pavlovich instantly interprets this as a death threat. But what was Dmitri's true meaning? Could he actually be contemplating patricide in response to his father's misdeeds and behavior?

How do you perceive Dmitri and his appearance? There's a striking resemblance between him and his father—they share the same vices and passions, from drinking and carousing to pursuing the same women. Among the three brothers, Dmitri mirrors his father most closely. Could this mean his outcry "Why should such a man live!" might reflect back on himself?

If he resembles his father, he's probably prone to lying as well. A question to ponder: do you think Dmitri was telling the truth about being late because his father's servant gave him the wrong time? Or is this merely an excuse and an attempt to make his father look "bad" in front of the monks? I find it peculiar that Dmitri would get the meeting details from his father's servant rather than from Ivan or Alexei, given that he appears to be in closer communication with them.

Let's examine Ivan's thesis on the immortality of the soul:

"in the argument that there is absolutely nothing on earth that compels people to love their fellow beings, that there is no natural law making humans love humanity, and that if love exists and has existed until now, it's not due to natural law, but solely because people believed in their immortality."

Ivan's expression of this thought is striking, particularly since later counterarguments will show that many non-believers in immortality lead moral lives, love others, and refrain from crime. The Elder perceives Ivan's own doubts about this thesis, yet Ivan remains deeply preoccupied with the soul's immortality. What drives this searching, questioning nature in Ivan's character? When Miusov describes him as the "Conscience of the Karamazovs" at the book's end, does this ring true?

A note about the women at the center of their argument.

This introduces us to what will become a series of complex romantic entanglements. What's particularly striking is Fyodor Pavlovich's challenge to his son for a duel—not only illegal and dangerous, but proposed under the most lethal conditions: "across a handkerchief." Such terms guarantee one participant's death. Had Dmitri truly wished his father dead at that moment, he could have accepted the challenge. Instead, he ignores it, suggesting both father and son recognize these threats as mere passionate outbursts.

For reference about the duel "across a handkerchief": when seconds would load only one of two identical pistols, the participants would choose their weapons, grab diagonally opposite ends of a pocket handkerchief, and fire at the command of the master of ceremonies. The survivor would understand that it was his pistol that had been loaded.

The most significant and complex moment in this chapter is Elder Zosima's bow.

What motivated this gesture? Though the characters will explore its meaning later, it's worth considering whether this was an impulsive act or a calculated one.

Notably, Zosima has already made a profound impact on all three brothers. With Alyosha, the relationship is clear—Zosima serves as his daily mentor and guide. With Ivan, he offered a blessing and, through their discussions, sparked new philosophical reflections, recognizing in him a "higher heart, capable of suffering." These words deeply affected Ivan.

Now comes this dramatic bow before Dmitri—a gesture that provoked intense reactions from all present.

Link to our discussion of this chapter.

Comments of

&Chapter 2.7 - The careerist seminarian

After the meeting with Zosima ends, everyone disperses. In this chapter, we follow Alexei. First, he escorts Zosima to his bedroom, which appears very poor. Zosima looks sick and tired. He tells Alexei something strange - that he should leave the monastery as soon as Zosima dies, a death which he already senses approaching.

Troubled and thoughtful, Alexei prepares to go to a formal dinner where his family should be. But on the forest path between the skete and monastery, he meets his friend Mikhail (Misha) Rakitin. This Rakitin has many interesting details about what's happening with the Karamazovs. We finally learn who Grushenka and Katerina Ivanovna (Dmitri's fiancée) are, and how they are, intentionally or by chance, involved in "love" triangles with various Karamazovs.

Some points that we discussed:

Elder Zosima asks Alyosha to leave the monastery after his death. He explains this by saying that Alyosha must see and serve the world, understand it, and marry before shutting himself away in the monastery. He's also certain that Alexei should stay close to both brothers - Alexei and Dmitri. What do you think about Zosima's instructions?

What are your thoughts on Rakitin's character? Pay close attention to him — he's a fascinating character who will play a significant role. While Alexei considers Mikhail Rakitin his friend, do you think he truly is one? His assessment of Alexei is particularly telling: "you always tell the truth, although you always sit between two chairs."

The meaning of Rakitin's name. His surname comes from a special type of tree - rakita (ракита) — Salix Caprea, which is kind of willow. In Orthodox Christianity, there is a holiday called Вербное воскресение (Goat willow Sunday) - a week before Easter. In many countries, this holiday is called Palm Sunday, but in cold Russia where palm trees are not common, the palm branch is replaced with a willow (rakita) branch.

Through Rakitin, we learn not only his interpretation of Zosima's bow and Ivan's article, but also intimate details about the Karamazov family's sensual nature. The entire family appears prone to passionate desires—according to Rakitin, not even Alexei is exempt. These romantic entanglements have manifested in two distinct love triangles.

The first revolves around Grushenka (Grushenka is a diminutive form of the full name Agrafena. In Russian, "grushenka" is also an endearing term for a pear fruit and pear tree), a woman whose true character remains controversial amid conflicting rumors. Both Fyodor Pavlovich and Dmitri harbor intense feelings for her, and their bitter quarrel stems largely from this romantic rivalry. Rakitin, who claims some connection to Grushenka—whether as a relative or friend remains unclear—has privileged access to Dmitri's confidences through her. A shrewd and calculating figure, Rakitin seems to collect and spread gossip with particular relish. His deep knowledge of everyone's affairs might even qualify him as a potential narrator.

The second love triangle centers on Katerina Ivanovna, a wealthy noblewoman and Dmitri's fiancée. Ivan has also fallen in love with her, creating yet another source of tension. She's the one who sent the letter to Alexei requesting to discuss Dmitri.

Link to our discussion of this chapter.

Comments of

& &Chapter 2.8 — A scandalous scene

In the original, the chapter is titled Scandal (Скандал). We've reached the end of the second book of the novel. It culminates in a release of tension—the grand scandal we've been anticipating throughout, erupting between the Karamazovs, Miusov, and the unwittingly involved monks (who serve more as observers and victims than participants). Miusov provides the gasoline, and Fyodor Pavlovich strikes the spark that ignites the flame.

Miusov, Kalganov, and Ivan Karamazov had already arrived at the monks' for the formal dinner when Fyodor Pavlovich—who had previously departed—suddenly reappears. Miusov had just begun to relax, even showing signs of kindness. But Fyodor Pavlovich's stubborn desire to provoke others took over, and he decided, despite everyone's dismay (including his own), to attend the dinner.

Thus the dinner ended before it could begin. Fyodor Pavlovich retreated to arrange his preferred entertainment—a drinking session at his house. When Landowner Maximov attempted to join them, Ivan roughly pushed him away. Without a word, Fyodor Pavlovich and Ivan departed in their carriage.

Some points that we discussed:

Miusov's mood changed dramatically. Once he was away from Fyodor Pavlovich, his demeanor improved—he let go of his anger and even became courteous and pleasant. He exemplified the type of person who professes love for humanity while despising individual humans. And Kalganov, his relative, remains present yet nearly invisible throughout the book, maintaining an almost constant silence. Why do you think Dostoevsky added him to these chapters?

Our main jester is Fyodor Pavlovich, who rides "on a foolish devil" into shameful depths. There's much to tell about him here. Consider his method, for instance - "he wanted to take revenge on everyone for his own nasty deeds." He operates by escalating situations. He begins by committing minor mischief, and if people take offense, he becomes offended in return and commits even more mischief. Interestingly though, it's noted that in his misdeeds he would only go as far as vileness, up to the point where he couldn't be imprisoned for it.

Ivan Karamazov's behavior. What do you make of his rough treatment of Maximov? Why did he do it? His father calls him Karl von Moor, a character from Schiller's play The Robbers. Dostoevsky was very fond of referencing this play, and Schiller in general. In brief, Karl is also a son in the play, and it raises questions of brotherly enmity. Schiller himself wrote about Karl:

"The robber Moor is not a thief, but a villain, not a scoundrel, but a monster."

It gives us something to think about regarding Ivan's true nature.

Link to our discussion of this chapter.

Comments of

&