1.7 What are they all up to in there, fast asleep — or has someone strangled them all?

This is one of the most important chapters of the novel. It contains the quintessence of half the title of the novel — namely, the very crime has taken place. And ahead are 5 more parts and and epilog

this is also one of the most challenging chapters for proper analysis. I wrote and rewrote it many times. I didn't say a lot, so if you have any questions about the chapter — write in the comments, and we will discuss it.

By the way, I invite everyone to join the chat. I am collecting questions for the first Q&A article. In it, we can discuss things that were not included in the articles to keep them from being too long. You can also express your opinion, whether you want to raise certain topics in the chat, overall I can make it open. Since the community is new and small, there is an opportunity to start making it comfortable for you right now.

Also, write your opinion on whether to make separate pages about each character.

When Rodion comes to the old woman after two days, she does not recognize him. The last time he came Alyona Ivanovna calmly opened the door for him and immediately started talking to him kindly. But now she, like a cornered beast, was immediately on high alert.

“Good Lord! What do you want?… Who are you? What’s your business?’ ‘But Aliona Ivanovna… you know me… Raskolnikov… here, I’ve brought something to pawn, I promised you the other day I would.’ And he held out his pledge.”

Why? Here we can start to raise the theme of doppelgangers, something that appears several times in Dostoevsky’s works. The Idea of one having a reflection of oneself, a twisted and revealing reflection living out there, and providing a counterpoint, an antithesis to who the character is or thinks he is.

In this case, it would seem that this doppelganger is not external. he is Raskolnikov, another Raskolnikov living inside the one who initially visited Alena Ivanovna two days ago. His features are twisted, he possesses a sort of aura that makes him unrecognizable now, even to himself.

But who did he become here: almost a dead man, condemned to death, or is he the embodiment of evil?

I have no answer to this question, as it is all a matter of interpretation. For me, Rodion here is a werewolf, a shapeshifter.

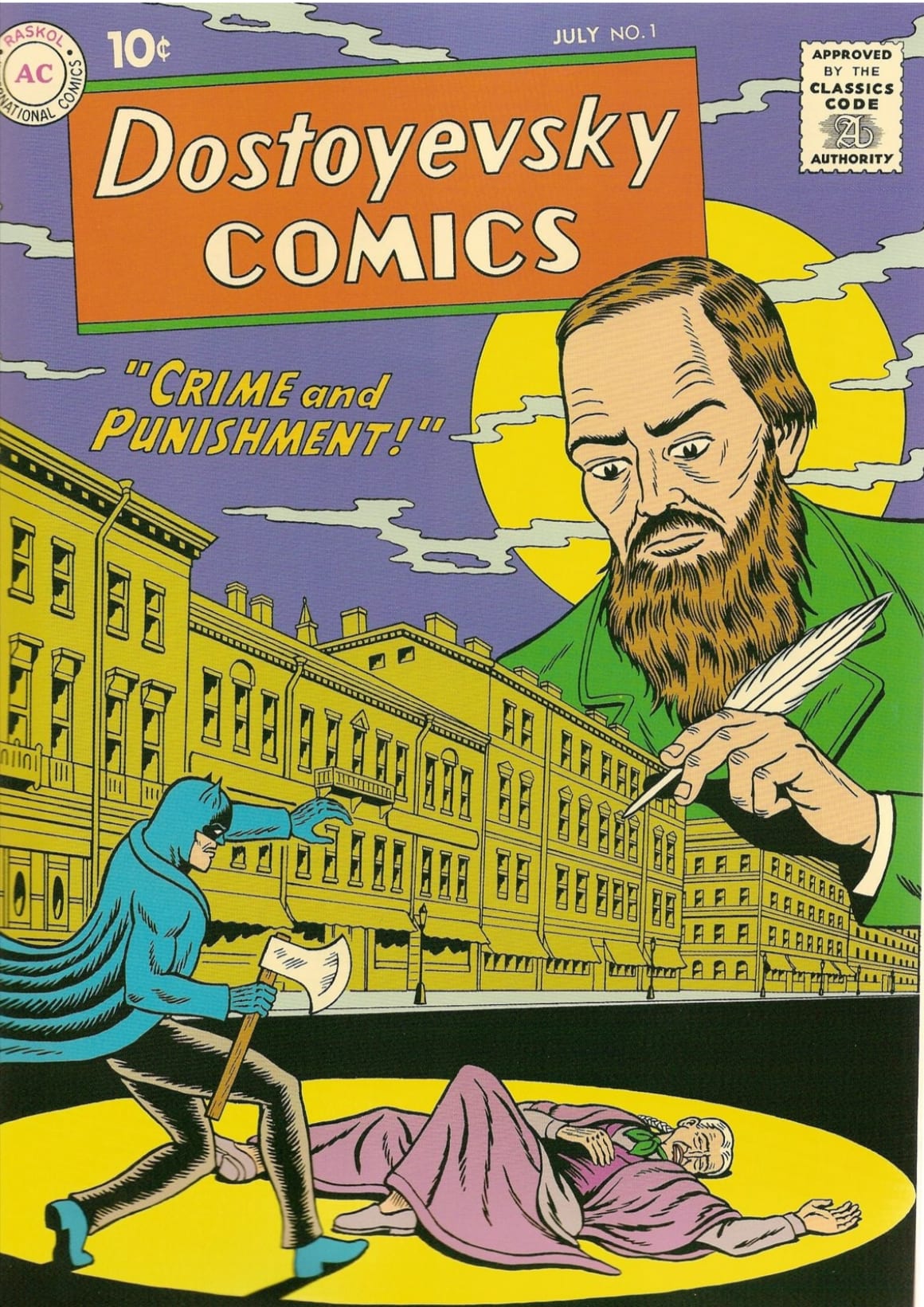

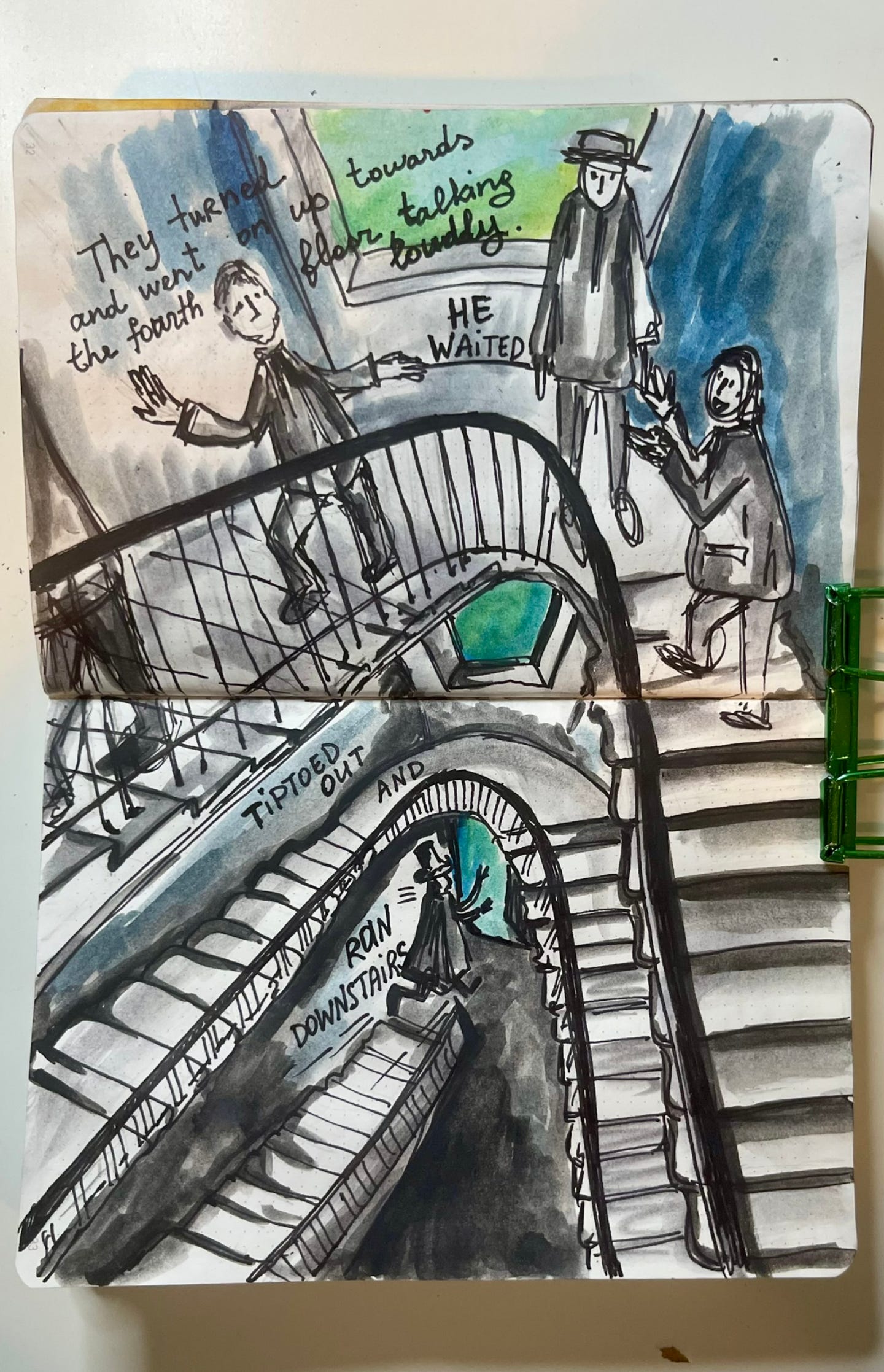

I will add frames from the comic inspired by the novel here. As you can see — Raskolnikov here is Batman, he is in a mask. And it is clear why the old woman does not recognize him.

Here is the comic book cover, in case anyone is interested in taking a look. However, it is short, and all the action of the novel takes place within 10 pages.

Real Crimes as the Basis of the Novel

Dostoevsky's novels are full of crimes—but the writer often did not entirely invent them, but took them from newspaper crime reports. He had a special interest in such publications: having been in a penal colony and listening to stories from criminals there, he learned to see social meaning in such incidents and read crime chronicles avidly until the end of his life. Some of these crimes are remembered and discussed among Dostoevsky's characters.

I want to talk about the cases that helped Dostoevsky write his novel.

1. The Case of Gerasim Chistov

The first reports of this double murder appeared in Moscow and St. Petersburg publications shortly after the crime was committed; then there were notes that the perpetrator had been caught. But the peak of interest in the case of Gerasim Chistov came in August-September 1865 when the capital newspaper "Golos" began publishing a stenographic report from the courtroom. From it, readers were able to learn the bloody details of the case and take a peek at the work of the investigators. At that time, this was unusual, and it was like a true crime series of the day.

The murder took place in Moscow on January 27 between 7 and 9 p.m. Gerasim Chistov came to his relatives' apartment when they were not at home, and the property was left in the care of the 62-year-old cook Anna Fomina. Chistov learned the day before that the old woman would be alone. A few weeks before the attack, he began to visit frequently and talk with the cook. Therefore, she let him into the apartment without questions or concerns. A 65-year-old laundress Marya Mikhailova happened to be visiting Fomina at the same time. The three of them sat down at the table, drank vodka, and had pickles as a snack. Under his coat, Chistov had hidden an axe—sharp, with a short handle. Chistov waited for one of the old women to go for more snacks and attacked the other.

"He instantly struck Mikhailova in the head with the axe, and she fell to the floor, followed by the chair she was sitting on. Chistov then struck her neck from the front with another blow. Then he prepared to deal with the cook, and just as she was about to enter the dining room from the kitchen with the pickles she had brought from the cellar on a plate, Chistov struck her with the axe, knocking her to the floor."

After this, Chistov searched all possible hiding places for valuables, stole the owners' money, silverware, gold, diamond jewelry, and a one hundred ruble lottery ticket, and left the crime scene. The total value of the stolen property amounted to 11,280 rubles.

That is a lot. Remember that Raskolnikov's mother received a pension of 120 rubles a year.

Chistov was pointed out by his relatives and acquaintances with whom he had met after the incident. He was detained within a day and categorically denied his guilt.

What Dostoevsky took into the novel

From the chronicle of this judicial process, Dostoevsky took the plot basis for the novel: a premeditated murder, two women - victims, the time of the incident between 7 and 9 in the evening, an axe as the main weapon, and hidden money.

The writer might also have liked the work of the investigators in this case, which we will see later - the prosecutor's attention to detail and the psychological state of the hero.

2. The Case of the Fake Parcel: The Murder of Collegiate Councillor Dubarasova

In August 1865, when the trial of Chistov had just begun in Moscow, another robbery-murder occurred in St. Petersburg — the murder of Collegiate Councillor Anna Dubarasova: the attack took place in her apartment. The commoner Stepanov tricked her into letting him is: he said he had brought a parcel from an acquaintance. The woman let him into the house. Stepanov had prepared a fake parcel, planning the murder in advance.

"Went to the attic, brought an empty jar and a brick, put them in a box... <...> ...Nailed the lid on one side with a nail, tied it with a rope (putting straw inside so that the empty jar and brick were not noticeable)".

Once inside the apartment, he slowly started unpacking the box. When Dubarasova leaned over to see why the messenger was taking so long, he took out the prepared brick and struck her on the head. The woman died almost instantly, and the criminal began to search the apartment.

He was caught by the relative of the murdered woman, Alexandra Dubarasova — he attacked her as well, but didn't manage to finish the job: the woman raised an alarm, and the neighbors were alerted.

Stepanov was caught a few days later. He categorically denied his guilt and demanded proof that the second woman was alive.

What Dostoevsky Took for the Novel

From the materials of this case, Dostoevsky might have borrowed the idea of the fake parcel. When going to the old pawnbroker, Raskolnikov takes with him a replica of a silver cigarette case. But in the real case, the second woman was lucky, unlike poor Lizaveta.

3. The Case of the Fake Tickets: The Professor of World History Leading the Fraudsters

In the pages of "Crime and Punishment," this case is mentioned by Luzhin. During his first meeting with Raskolnikov, he actively joins the discussion about the murder of the old pawnbroker, contemplating the global changes in society. That's when we’ll discuss it in more detail.

How many people did Raskolnikov kill?

This question might seem strange: it's clear that he killed two. But it's worth remembering that Lizaveta, the sister of the old pawnbroker, was "constantly pregnant," and from the drafts of "Crime and Punishment," it follows that she was pregnant at the time of the murder: in one draft, Nastasya says that the deceased child was "doctor's," conceived by Doctor Zosimov, and in another, a completely shocking detail is reported: "And they even cut her open. She was six months pregnant. A boy. Dead." According to one version, the exclusion of this part was insisted upon by the novel's publisher, Mikhail Katkov. If we don't count the unborn child, who ultimately did not make it into the final text, the old woman represents metaphors for different things.

By killing the old woman, Raskolnikov killed his future, himself.

I will tell you more about the interesting metaphorical murder of the old woman and the murder of God in the next article, about the first chapter of Part 2.

If for Raskolnikov the murder of the old woman was not a crime, the same logic he can’t apply to the unexpected murder of Lizaveta—as he defined it for himself. It is interesting, will he later differentiate between these two murders, are they equivalent to him? What do you think?

As you may have noticed, the characters in the novel are talkative. This is a tradition of Russian literature, as Gogol did, so did Chekhov, and many other authors.

And what is so special about the name Raskolnikov? I have already written that this name is entirely composed of contradictions, at the root of his surname is the word — split (раскол). The name — Rodion, is consonant with such words as native (родной), motherland (Родина), kin (род). The closest and dearest. The name and surname also conflict with each other.

The surname Raskolnikov indicates his origin from an Old Believer ("schismatic"/ раскольник) family — and, of course, hints at the axe. Schismatics (Раскольники) appeared in the 17th century, after church reforms that led to a split in the Russian church.

Moreover, the initials of Rodion Romanovich Raskolnikov — (P.P.P. in Cyrillic) — even visually resemble axes: it is possible that this is a hint at the three murders committed by the hero (the old woman, Lizaveta and her unborn child — or, if there was no child, the symbolic murder of himself).

Overall, Rodion seemed to have very cleverly avoided witnesses. But is that really the case? Did anyone see him, or was luck on his side?

So fortunately everyone left the staircase, and when they were coming back up — he managed to enter the open apartment. What drove him? The devil?

So, we have finished the first part of the novel. Now we know about the crime. What do you think about it? What punishment do you think Raskolnikov deserves?

Let's discuss the chapter!

Many are fascinated by true crime stories. Dostoevsky and Truman Compote both studied true crimes and gave us famous books. Why do minds seek to live violence vicariously? Perhaps Raskolnikov did, too, but it overtook him and “vicariously” turned into “actually.” He is Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. I am still not sure of his motive. The idea of saving others with the money he gained seemed to have been lost. Going through this chapter one gruesome detail at a time was difficult.

I must have missed something here, since it's not clear to me that helping the poor was ever part of R's plan?I know he overhears that 'Robin Hood' type theory when the students are talking, but I can't see that he adopted it? From my reading it doesn't really say what he plans to do with the proceeds of the robbery, although his needs are very obvious.

I think R will view these two murders quite differently. He has already decided that killing the old woman is 'not a crime' After that murder he immediately sets about his intention of robbery.He felt in "full possession of his faculties, free from confusion or giddiness, but his hands were trembling."

Having to also murder Lizabeta is a total, unanticipated shock. "Fear gained more and more mastery over him, especially after this second quite unexpected murder." He has feelings of "loathing and horror" at what he has done. This is not a murder he can rationalise in the same way he did with the old woman. I think it will be obvious, even to him, that that murder is about not getting caught.

It's interesting that the derivation of his name points to a "split", a play on words which a reader in a translation misses. But I see how this ties in with the idea of the doppelganger that you suggest, an internal 'other' within Rodion. I think I suggested last time that in his debilitated fantasies Rodion has entered an abstract world; he is 'other' to himself. I think most of us probably have an internal 'other' but are fortunate enough not to meet circumstances in which our darker side takes over, or in which our sense of right and wrong, is severely tested.

There are lots of ideas in the text, in your suggestions, and in the chat, and I expect all this to slowly unravel and become clearer as the novel processes.