At the beginning of the chapter, Dostoevsky deviates slightly from the narrative and inserts a flashback.

In Dostoevsky's initial concept, the main motive for the crime was the desire to provide for his mother and sister. But then, as Raskolnikov's character became more complex, money took a back seat (although the letter from his mother, which further exacerbated the protagonist's agitated state, certainly played a role in his decision). The main desire became to step over himself, over the social barriers and norms.

The novel has a system of "triggers," coincidences that determine the action, and "doubles" who copy Raskolnikov's words or deeds. It is quite possible that he would not have decided to commit the murder if he had not overheard a student in the tavern talking about the same old moneylender woman.

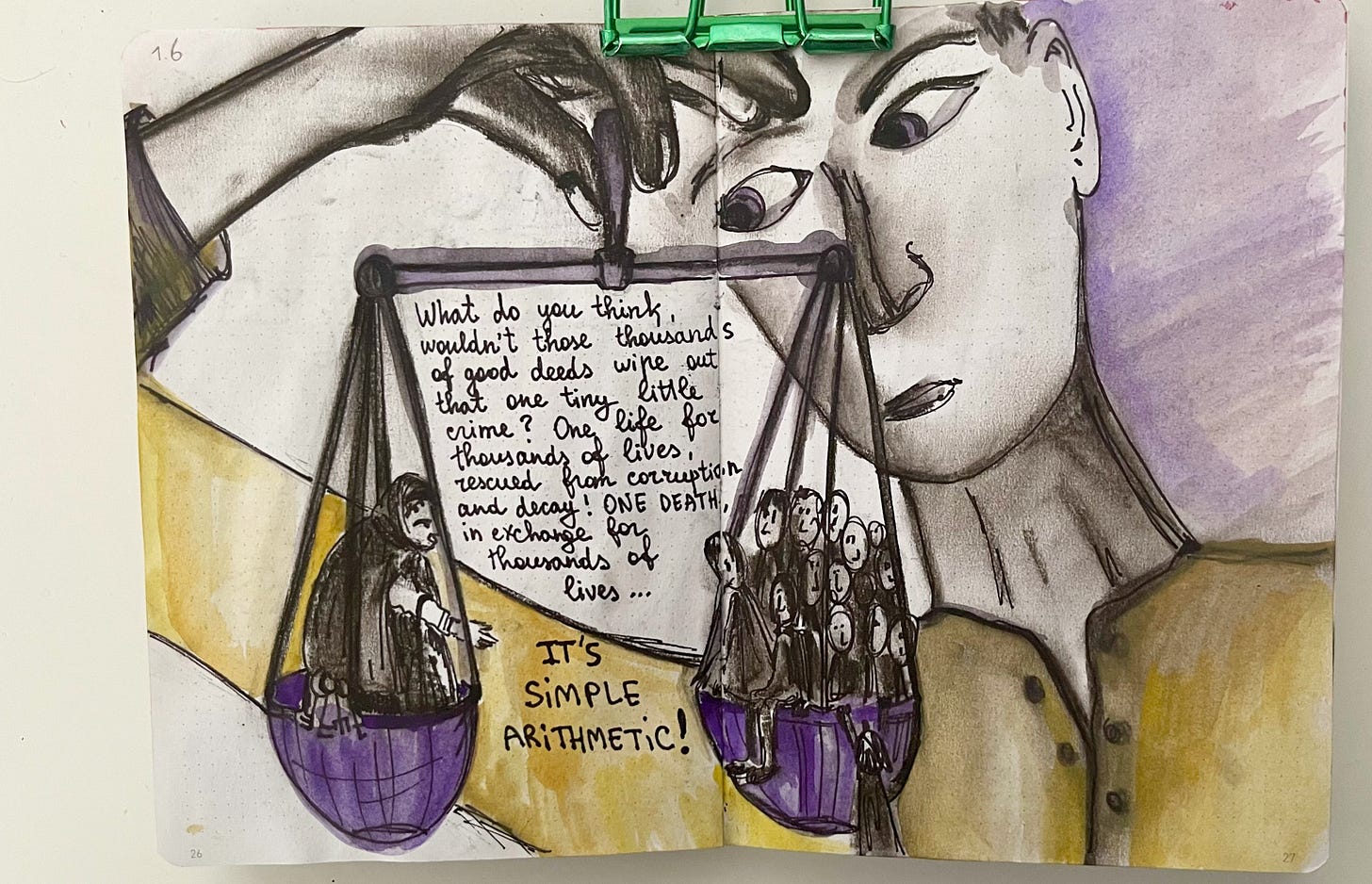

“Listen, I want to ask you a serious question,’ said the student in some excitement. ‘I was joking just now, of course, but look here: on the one hand, here’s this stupid, pointless, worthless, evil, sick old crone, whom nobody wants, in fact she does harm to everybody, she herself has no idea what she’s alive for, and tomorrow she’ll die in any case. Do you see? Do you see?’

‘All right then, I see,’ replied the officer, looking closely at his excited friend.

‘Let me go on. On the other hand, there are fresh, young, vigorous people perishing needlessly for lack of support, thousands of them, all over the place! <…> One life for thousands of lives, rescued from corruption and decay! One death, in exchange for thousands of lives—it’s simple arithmetic! Anyway, what does the life of that consumptive, stupid, wicked old crone count for, when it’s weighed in the balance?

Raskolnikov is distraught that the student expresses "exactly the same thoughts" that torment him. "This insignificant tavern conversation had an extraordinary influence on him in the further development of the case" — and the matter may be precisely that Raskolnikov could not tolerate competition.

This conversation has a literary prototype — the dialogue between Rastignac and Bianchon from Balzac's novel "Father Goriot" In that dialogue, the two characters discuss a thought experiment proposed by Jean-Jaque Rousseau. What if one “could make a fortune by killing an old man somewhere in China by mere force of wishing it, and without stirring from Paris?” And one of the characters considers the question, by first asking if the man is extremely old, before coming to his inevitable senses - no, if he’s old or young, healthy or sick, he wouldn’t do such a thing. But what if you had to make money for your sister? Young, wonderful, full of life sister? The answer is still no, and the character compares this way of solving your problems with the cutting of the Gordian knot.

Dostoevsky sharpens the conditions of the "moral problem" in a way similar to Balzac. Here, the goal is not personal enrichment but "service to all humanity." Dostoevsky gives it an "arithmetical" justification. And there even seems to be a benefit for humanity — to kill an old useless woman, who would soon die anyway, so that millions of people could receive her accumulated wealth and not live in poverty.

But is the old woman really rich enough to help millions? And why kill her at all if the goal is robbery?

Raskolnikov doesn't even think about this; he already has a desire to test this theory in his head.

This theory of Raskolnikov reminds me a bit of the "Trolley Problem" — a thought experiment in which an uncontrollable train is rushing down the tracks, toward 5 people laid out on them. If nothing is done, the train will surely kill 5 people. However, you are in front of a lever, which, if pulled, will divert the runaway train to another track, where only one person lies.

If you do nothing, 5 people die. If you pull the lever, only one dies, but it is your action that makes it happen.

Is one person's life worth more than the lives of five?

Similarly, Raskolnikov now finds himself at this lever in his opinion. He believes that he has no choice and that the tram is already speeding. And he can kill the old woman to save millions on the other track. It’s not even a matter of not having a choice, it’s one’s duty to do something.

What do you think about Raskolnikov's theory? Can the death of one save the lives of millions?

“Are you ill, or what?”

What is wrong with Raskolnikov? Even at the beginning of the chapter, Nastasya asks him several times if he is ill. But what kind of illness is Dostoevsky really asking about? Is it a physical condition or a mental problem?

What psychological tendencies led to Raskolnikov's crime?

Diagnosing literary characters is a risky business, but something can already be said about Raskolnikov's psychological state. Raskolnikov swings from one extreme to another: first, he wants to save a girl from harassment on the boulevard, then he says, "Let him have his fun"; first, he gives all his money to Marmeladov, then reproaches himself: "They have Sonya, and I need it myself"; before the murder, he thinks through small details like a loop for an axe under his coat, and then makes one mistake after another. Japanese researcher of Dostoevsky, Kennosuke Nakamura, writes that Raskolnikov "is in severe depression." There will be even more such details further in the novel and other characters will diagnose him.

Dostoevsky did not like being called a psychological author, and he had ‘a negative attitude towards contemporary psychology — both in scientific and artistic literature and in judicial practice." Suffering, the "indecisiveness" of the soul in his prose, is not a subject for medical analysis; Raskolnikov is exceptional as he is a human being in general.

The presence of extraordinary influences and coincidence

Chance plays a significant role in the preparation and commission of the crime. Rodion himself says at the beginning that his belief in coincidences has grown lately. He is a puppet in the hands of chance, fate, or the devil. And even though he thought a lot about the crime a month before it happened, everything was altered an shifted by sheer chance.

Although it seems that Raskolnikov is thoroughly preparing for the crime, chance plays just as significant a role. Everything here relies on this balance and uncertainty. And surprisingly, Rodion even gets lucky with his mistakes.

What Raskolnikov thought through:

decided he would kill with an axe, and take it from Nastasya's kitchen

decided how he would carry the axe

realized he should not wear his noticeable hat

noted who else lived in the house with the old woman

measured the “730” path, walked to the old woman's house

made a fake pledge

Incident:

found the axe in another place, by accident

did not sew the loop to the coat in advance. And in general, going in 35 degrees Celsius heat in a coat is crazy. But it was dense enough that the axe couldn't be seen there.

still wore his hat

got lucky that many of the old woman's neighbors had moved out, and the painters doing repairs did not pay attention to him

found out that Lizaveta wouldn't be there at 7 pm, but overslept and got to the old woman only at 7:30 pm

went a different way, not the one he measured.

By the way, Dostoevsky himself used to walk this route past the Yusupov Garden shortly before he began working on his novel. He walked to his creditor Stellovsky, who forced the writer to sign a contract to publish all his works for free if he did not write the novel on time. Thus, Raskolnikov's route is filled with special memories for Dostoevsky, associated with his creditors, debts, and despair.

“I suppose a man being led to his execution will fix his mind on every object he encounters on his way.”

For Rodion, this path is akin to the path of a person sentenced to death, leading to the executioner. It is believed that Dostoevsky took these thoughts from Victor Hugo's novella "The Last Day of a Condemned Man" (1828). He considered this book one of his favorites and a masterpiece. "The most realistic and truthful work of all he (Hugo) has written." It was on Dostoevsky's initiative and with his help that this novella was first translated into Russian.

One might think that Fyodor Mikhailovich could have taken these thoughts from personal experience, as he was once sentenced to death and even stood on the execution site. However, the situation there was horribly strange, as this was a form of psychological torture. Dostoevsky was already pardoned and his death sentence was changed to penal labor, but he and others with him were not told that, and were led to the execution site, and spread out in front of a firing squad, before the announcement was read about them being spared. Dostoyevsky later received a full pardon from the Emperor.

He would keep an inexorable hold on his rational judgement and his will, throughout the execution of his plan—for the single reason that what he had planned was ‘not a crime’.

Raskolnikov does not consider that he is committing a crime. Why? Is it a death sentence for him? A sacrificial act? A test?

This is the most important question in the novel — what this murder means to Rodion. Why does he not consider it a crime, and what will he consider punishment? We will discuss this in the remaining 5 parts of the novel. After all, it turns out that in a novel of 6 parts, only the first part is the crime and the remaining 5 are the punishment.

3 ominous rings at the door... The old woman opens the door.

Raskolnikov does not believe until the very end that his thoughts will turn into action. He had many impulses for this, he gathered them like beads on a string. But we will analyze this in the next article when we find out whether he will really kill the old woman or still change his mind. Will chance interfere again?

Excellent analysis Dana. I liked that you brought up the diagnosis angle as it’s something that I’ve been thinking about too. There certainly seems to be something going on with his mental health. Boys get sad too, to use a current meme.

This chapter was so interesting. There seems to be a clear, albeit faulty, logic to his motivations. He's not a cornered animal driven by desperation in the way I suspected he might be from earlier chapters. It's also interesting (I'd say funny but that's not quite right) that if you're looking for "signs" to justify your actions you surely will find them. The thought-experiment-gone-bad aspect reminded me of the Hitchcock film "Rope", where a philosophical discussion of justified murder led to the warped plan to commit the perfect crime just to show it could be done. As an aside, your note reminded me of the website for increasingly absurd trolly problems: https://neal.fun/absurd-trolley-problems/