1.4 Or else give up my life altogether!

It's hot outside, daytime. The calendar reads July 8, 1865. At the end of the last chapter, we left Rodion in the middle of the street.

Raskolnikov is walking through St. Petersburg towards Vasilievsky Island, north from his home. He went out onto Voznesensky (Ascension) Prospect (Avenue) and walked towards Vasilievsky Island. He meets the drunken girl on the bench at Konnogvardeisky (Horse Guards) Boulevard — which means he turned left and did not go to the Palace Bridge and the Winter Palace. He decided to bypass this affluent part of Petersburg and walk through the working-class neighborhoods to be less noticeable.

After reading the letter, he is angry: at his mother, at his sister, at Luzhin, whom he has never seen, and at himself. He encounters a drunken young girl, about 16 years old, who is walking down the boulevard, then sits down and falls asleep on a bench. Rodion feels a desire to save her. He sees that another man likely intent on taking advantage of her unconscious state and wants to shield her from him. But how? He gives a policeman 20 kopecks to put her in a cab and send her home.

But will she really be safe? Did Raskolnikov really help the girl?

What do you think this strange urge in Raskolnikov is — to help others while simultaneously planning his crime. Is there a struggle between a decent and a criminal person within him? Is he trying desperately to prove to himself that he’s decent, and patch up the tears that already appear in the moral fabric?

Interesting details from the chapter

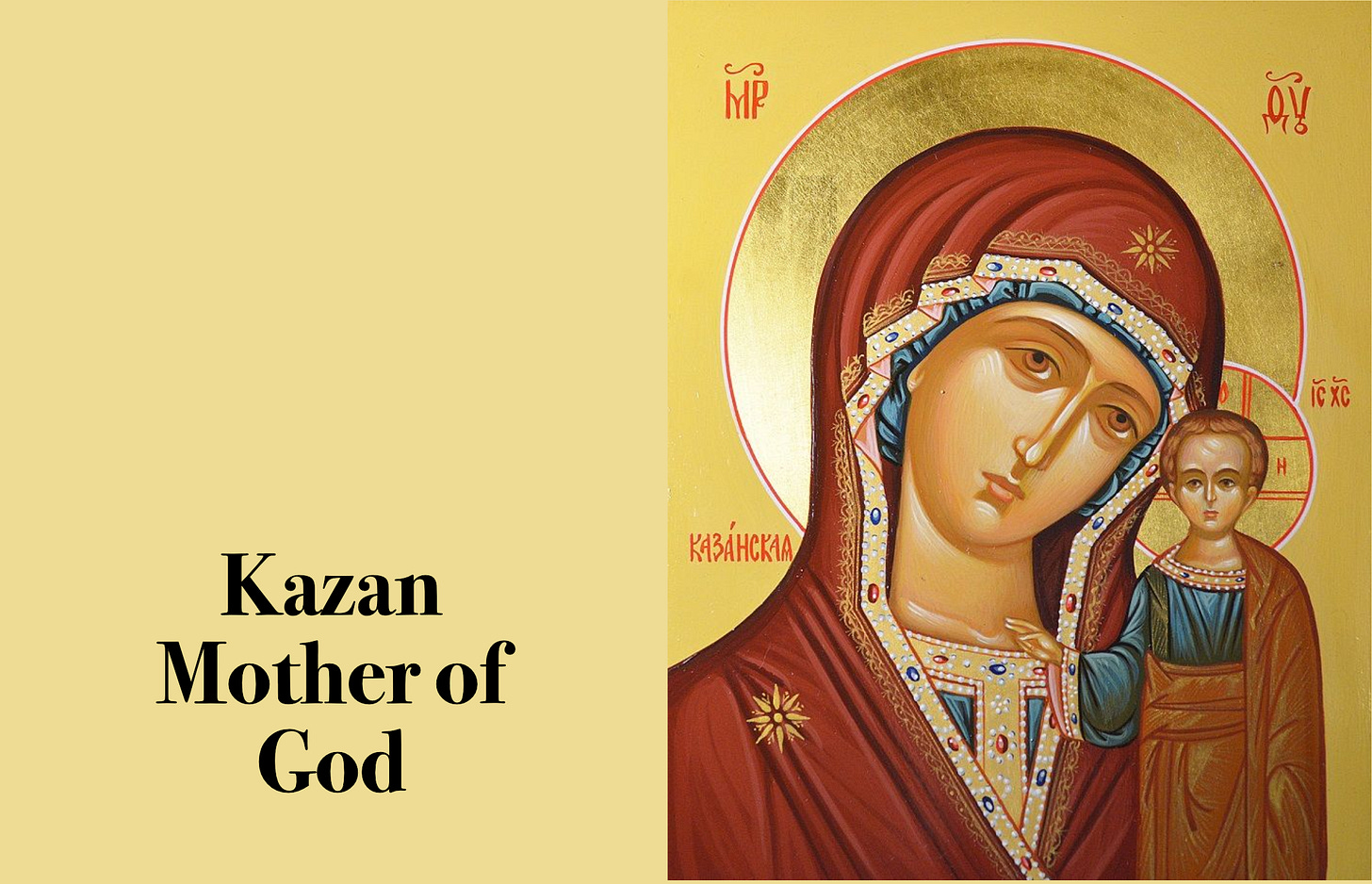

I see it all, I know what a lot you want to tell me; and I know what it was you were thinking about all night, pacing up and down the room, and what you were praying about to Our Lady of Kazan* who stands in Mamasha’s bedroom.

Kazan Mother of God. The mention of this patroness is not accidental. On July 8 the Appearance of the Icon of the Kazan Mother of God is celebrated. Clearly, this is not a coincidence; Dostoevsky carefully considered such details, structure, and dates. As we remember, all the events of the novel take place between two fasts, that is, during a time when one can eat meat and theoretically be less strict with oneself, preparing for a period of purification during the upcoming fast.

Among other icons of the Mother of God, the Kazan icon is distinguished by the fact that it was the only one that “appeared” from the earth. In 1579 there was a fire that destroyed a large portion of the city of Kazan. And according to tradition, a vision of the mother of God came to a young girl, telling her to dig in the soot-covered ground, to find the icon.

The story has established a mystical connection of the icon with the mother earth. And this connection is extremely important for Dostoevsky's work — showing repentance to the earth, praying to it, kissing it. And the Kazan Mother of God appears to Rodion before the crime. He is at a crossroads, and this should be a sign for him.

Moreover, the events of the novel take place in the part of St. Petersburg that is associated with Kazan because of the Kazan Cathedral, where this icon was located.

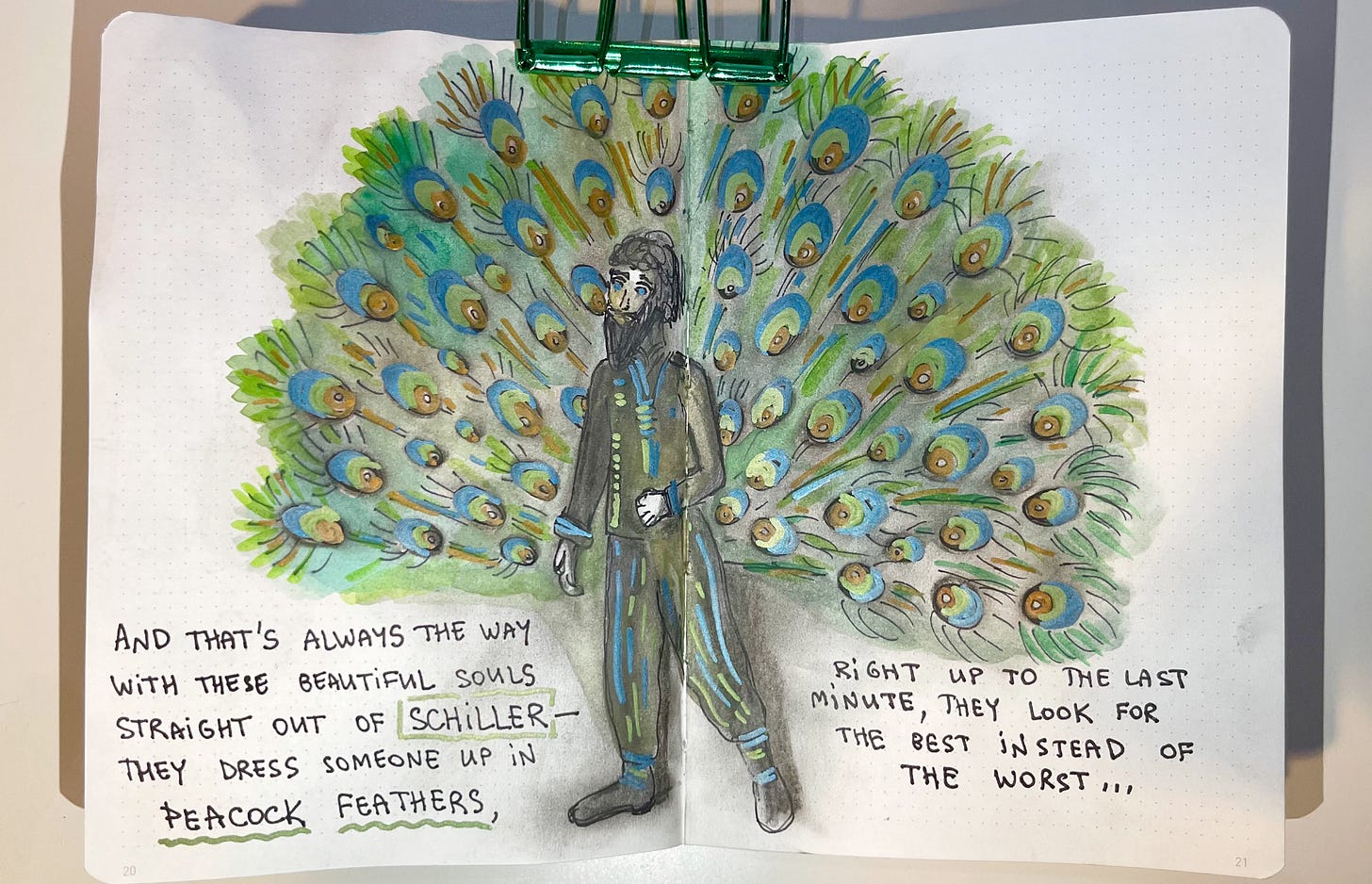

And that’s always the way with these beautiful souls straight out of Schiller—they dress someone up in peacock feathers, right up to the last minute, they look for the best instead of the worst, right up to the last minute, and even if they suspect that the medal has a reverse side, they’ll never breathe a word of the truth to themselves till it’s too late, the very thought of it makes them cringe, they push the truth away with both hands, until the very moment when the man they’ve dressed up in false colours comes and personally thumbs his nose at them.

"Beautiful soul" is a category of Schiller's philosophical aesthetics. It expresses the idea of "Perfect human nature," where feelings and moral duty are in harmony. In the context of Raskolnikov's monologue, however, this context is exacerbated by Rodion. The desire to sacrifice oneself for a loved one can turn into the selfishness of self-sacrifice. That is, it becomes a discordant action in which feelings and moral duty are opposed to each other.

“dress someone up in peacock feathers” — Here Dostoevsky altered the phrase "a crow in peacock's feathers" (”ворона в павлиньих периях”) — this is said about a person who ascribes to themselves qualities that are not inherent to them. This phrase is taken from Krylov's fable "The Crow".

Sticking a peacock feather in its tail, The crow went to walk proudly with the peacocks...

(”Утыкав себе павлиньим пером хвост, Ворона с павами пошла гулять спесиво…”)

Raskolnikov is specifically angry at Dunya and his mother for agreeing to marry Luzhin only out of moral duty, disregarding their feelings. Rodion does not want anyone to sacrifice themselves for his sake.

“she wouldn’t sell her soul, she wouldn’t sacrifice her moral freedom for the sake of comfort—she wouldn’t sacrifice it for the whole of Schleswig-Holstein, never mind Mister Luzhin”

Where did this duchy in Europe, Schleswig-Holstein, suddenly come from in Rodion's thoughts, why does he care about it in St. Petersburg? This diplomatic issue was prominently on the agenda in 1865 — the dispute over who owned this land was between Denmark, Prussia, and Austria. This indicates that Rodion was following the news, and the pressing political events. And this hyperbole of "giving away the entire duchy" Raskolnikov uses as a possible material benefit from his sister's marriage to Luzhin. Which also resonates with him as a problem of moral responsibility within the framework of the story.

Repeal of the smoking ban

An unfamiliar suspicious man, who, like Raskolnikov, was watching the drunk girl is “standing there, pretending to roll a cigarette…”

This is a sign of the times; until the summer of 1865, rolling cigarettes was unacceptable on the street and in public places because smoking on the streets was prohibited due to the threat of fires. Smoking was forbidden not only to pedestrians but also to those riding horses. A large fine was imposed on the violators. However, at the beginning of July 1865, a Senate decree was passed allowing tobacco smoking on the streets.

Despite the permission, the number of smokers in the city did not significantly increase: smoking on the street was difficult. Matches began to be widespread only at the end of the 19th century. Instead, coal-carrying pots and Döbereiner's lamps were in use, which were difficult for pedestrians to carry. Dostoevsky, by the way, was an avid smoker.

After this scene with the drunk girl, Rodion goes to Vasilyevsky Island to see Razumikhin, his university friend with whom he has not communicated for a long time. Unlike Rodion, who is immersed in not-so-positive thoughts, Razumikhin is described as a cheerful and joyful person.

By the way, his surname also speaks to his character, derived from the word "Reason" (Разум / Razum). Will he indeed be the mind of the novel, acting sensibly and wisely?

In any case, he sounds like a pleasant character whom I can't wait to meet. Already in the next chapter.

NB. Veiled literary reference

“He must make up his mind, decide on something, anything—or else… ‘Or else give up my life altogether!’ he suddenly cried out in a frenzy. ‘Meekly submit to my fate, as it is now, once and for all, and stifle all that’s in me, and give up any right to act, or live, or love!”

In this chapter, some literary critics see echoes of Hamlet's famous "To be or not to be" soliloquy.

To be, or not to be, that is the question:

Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles

And by opposing end them. To die—to sleep,

No more; and by a sleep to say we end”from Hamlet*,* W. SHAKESPEARE

What do you think about this? Is there anything in common between Hamlet and Raskolnikov?

Oh! I love the comparison to Hamlet! If ever there was a literary monomaniac, it is he. Obsessed by the apparent murder of his father, Hamlet is drawn deeper and deeper into darkness that eventually results in becoming a murderer himself and eventually takes his and the lives of all he loves (with a few extra to boot). This doesn’t bode well for our good friend Roskolnikov.

I still cannot think of Raskolnikov as a villain. Same for Marmeladov. To me, they're both individuals that don't have anywhere else to turn to. "Every man must have somewhere to go," and neither of them has that. Raskolnikov is in such a deep state of depression he can't even feed himself; and society has no safety net set up for him, or for people like him, for prostitutes, alcoholics, starving children. They call them statistics so they don't have to think about the moral implications. This is not to say that him (I'm assuming) murdering someone is justifiable, rather to me Dostoevsky is saying that A) even the lowest of criminal should be treated with Christian charity and b) society as a whole should think long and hard at why poor people end up committing crimes.

Take the girl we meet in this chapter. This is a teen who has just been raped, pure and simple. Raskolnikov's reaction should be the most obvious one, getting angry and trying to help. Instead we get a rich guy wanting to take advantage of her and fearing no consequences, and a policeman kind of shaking his head and going, "tsk, tsk, what a pity," trotting around not knowing what to do. What he should be doing is raining fire and brimstone! Raskolnikov is deeply, deeply aware that this girl is doomed and there is nothing he can do to fix things, he can't even fix himself! He's turning into a nihilist because he's so powerless.